The Voice referendum explained: Why changing the Constitution is so hard

The Voice referendum is less than a month away, but it’s not easy for the Constitution to be changed. This is why it’ll be so hard for the Voice to pass.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ahead of the October 14 referendum on the proposed Voice to Parliament, we are presenting a series of explainers to clarify what it’s all about.

Today we look at why it’s so hard to amend the Constitution before Australians go to the polls to cast their vote.

WHAT IS THE CONSTITUTION?

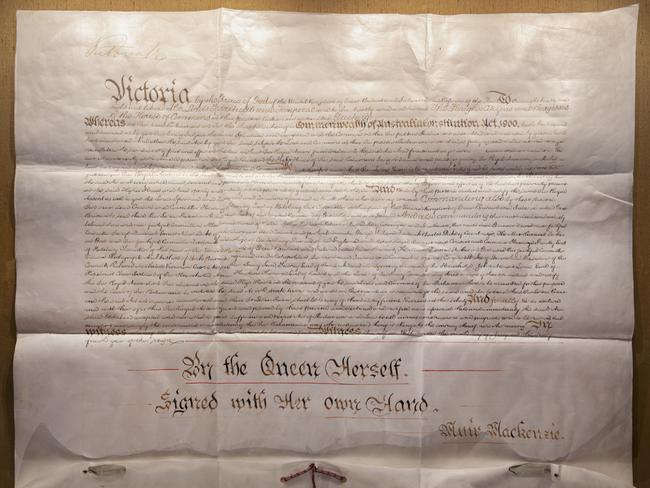

Constitutions are documents which set out the rules by which countries are governed. Most nations have one, although there are notable exceptions. The UK and New Zealand have no one single document that sets everything out: they rely instead on a patchwork of different documents and traditions.

Australia’s Constitution was developed in the late 19th century as the states and territories came together as a federation. The Constitution and the country came into effect on the same day – January 1, 1901.

In its eight sections and 128 parts, the Australian Constitution sets out the framework for how the country is run, with power split between an elected two-house federal parliament, six state governments, a High Court, and a Governor-General, representing the British monarchy.

WHAT IS A REFERENDUM?

Members of parliament do not have the power to amend the Constitution. Nor does the Governor-General. The Constitution stipulates that only the people have that power, which is exercised by a vote of all citizens on the electoral roll – basically Australians aged 18 and over.

In total, 44 proposed changes to the Constitution have been put to the people since 1901 with 21 posted at the same time as a federal election.

It’s 24 years since we last held a referendum, when we voted against becoming a republic and adding a preamble to the Constitution in 1999.

GOT A QUESTION: If you’re confused about the Voice, submit your question for us to answer

WHY DON’T WE TALK ABOUT AMENDMENTS LIKE AMERICANS?

Watch an American TV show, or movie, or news bulletin, and before too long you’re bound to hear a reference to a constitutional amendment – and more often than not, that reference will be to the “second amendment”, the 1791 law which gave Americans the right to “keep and bear arms”.

So, why don’t we talk like that in Australia?

“At an overall level the Constitution doesn’t play as prominent role in our public imagination as compared to the United States,” said Sydney University law expert Associate Professor Elisa Arcioni.

“The US Constitution really emerged out of fierce fighting and independence [from Britain] whereas the Australian Constitutional history is much more muted. It wasn’t about creating something from nothing and nor was it about railing against another force. Our Constitution just doesn’t have the hold on everyone’s day-to-day lives or experience.”

WHAT MAKES A REFERENDUM SUCCESSFUL?

SECTION 128 of the Constitution requires a double majority for a constitutional referendum to succeed — not only must a majority of voters across the nation support the change, four of the six states must also have a majority yes vote.

It’s not an easy criteria to meet. Of the 44 referendum questions put to the Australian people since 1901, only eight have been successful, and since 1984, all have failed.

Assoc Prof Arcioni says the double majority is not an inadvertent flaw, but an actual design feature of the Constitution.

“(The) mechanism [for success] was set up in the drafting of the Constitution to deliberately make it difficult to change the wording,” she said. “That was because the colonies engaged in fierce negotiation and compromise to create the national Constitution, and they wanted to retain [their] power in that process of change.”

IS THE CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS FAIR?

While Australia has an enviable record of free and fair elections, when it comes to our system of government, there are a few quirks that seem to go against the democratic ideal that all votes should have the same value.

“Something that many people would be surprised to know is that the Constitution is not about formal equality; we actually have entrenched inequalities,” said Assoc Prof Arcioni.

Prime example: the Senate.

While the states vary widely in the number of voters they have (from 400,000 in Tasmania to 5.5 million in NSW), the Constitution allocates 12 senators to each.

Another inequality lies in how voters in the territories are counted in referendums. Currently there are more than 315,000 people on the electoral roll in the ACT, and another 149,000 in the NT – but those combined 464,000 Australians have less of a say in the outcomes of referendums than the voters in the states.

While their individual votes are counted as part of the national tally, they’re ignored completely in the majority of states calculation.

And if you think that’s unfair, consider this: people who lived in the territories didn’t get to vote in national referendums at all until after 1977 when they were accorded that right in a successful referendum vote.

WHAT REFERENDUMS HAVE BEEN SUCCESSFUL TO DATE?

Australians have voted for diverse constitutional reforms since 1901:

– enabling elections to both Houses of Parliament to be held at the same time (1906);

– enabling the Commonwealth to take over state debts (1910);

– enabling reform to federal/state finances (1928);

– giving the Commonwealth power in the area of social services (1946);

– giving the Commonwealth power to enact laws for Aboriginal people (1967);

– giving Territorians the vote in future referendums (1977);

– mandating 70 as the retirement age for judges (1977);

– ensuring casual Senate vacancies are filled by a person of the same political party (1977).

Assoc Prof Arcioni said there’s little to link Australia’s eight successful referendums, and even the belief that all benefited from bipartisan support is subject to some conjecture.

“The variety of questions that have been put to referendums are really disparate, so it’s hard to draw any particular pattern from the past,” she said.

HAVE MANY REFERENDUMS BEEN ABOUT INDIGENOUS ISSUES?

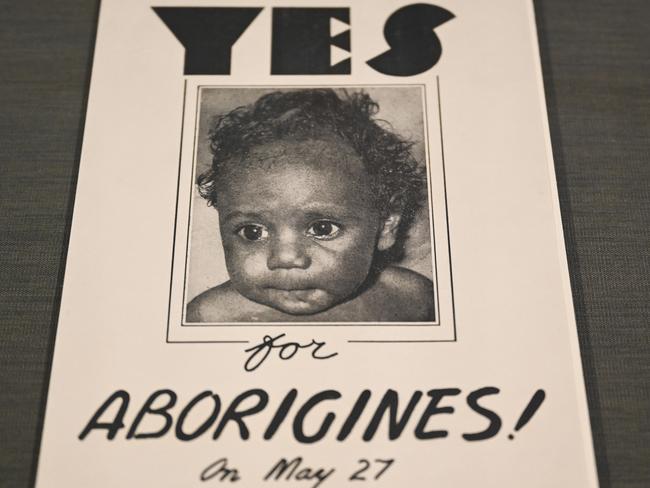

The 1967 proposal for the Commonwealth to enact laws for Aboriginal people was the most emphatically supported referendums in Australia’s history. Almost 91 per cent of voters were in favour and the question was supported by all states.

But other referendums questions pertaining to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been lost.

An earlier version of the 1967 proposal was put to the people in 1944, as one of 14 areas of law where the Commonwealth sought additional power, but it failed to attain a popular majority, and a majority of states.

The 1999 proposal for a Constitutional preamble would have included a statement of recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, but more than 60 per cent of voters were opposed.

Originally published as The Voice referendum explained: Why changing the Constitution is so hard