Pitjantjatjara artist Noli Rictor wins Australia’s biggest art prize NATSIAA 2024

The youngest person experience the moment of ‘first contact’ between an Aboriginal person and settlement Australia has been awarded a $100,000 prize at the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards.

Indigenous Affairs

Don't miss out on the headlines from Indigenous Affairs. Followed categories will be added to My News.

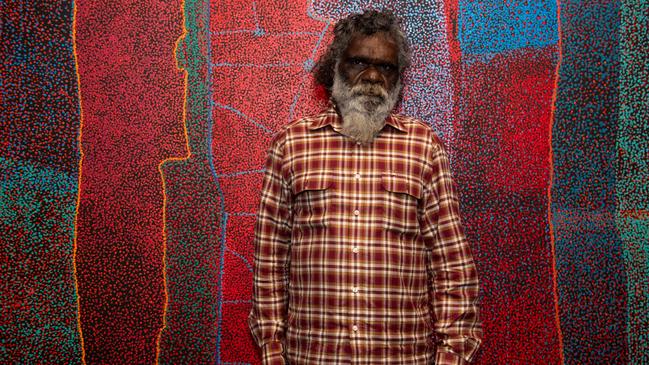

Through vivid red, blue and yellow dots Pitjantjatjara artist Noli Rictor brings alive the ‘living space’ of his Spinifex Country, between water and desert, life and the void, and between black and white.

This is the land where Mr Rictor became possibly the youngest person experience the moment of ‘first contact’ between an Aboriginal person and white settlers in Australia, coming across a group of settlers in 1986 in the remote Great Victoria Desert’s of Western Australia.

On Friday Mr Rictor was named the winner of this year’s Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, returning home to his Spinifex Country with Australia’s biggest art prize of $100,000.

Standing in front of his 6 sqm painting, the soft-spoken Pitjantjatjara man shared the story of Kamanti, home of the Wati Kutjara Tjukurpa (Two Men Creation Line) a father and son water serpent and their journey across the Spinifex Lands on ceremonial business.

Speaking through his studio manager Riley Adams Brown, Mr Rictor showed the lands of the Pila Nguru people — those “from the space between the dunes” — with its rocky ridges, steep sand-dunes mark the pathways carved out by the ancestral beings.

“Their footprints through the land are known to Noli,” Mr Adams Brown translated.

“They didn’t really worry about the sand dunes, because the living spaces are in between — that’s where all the waters source, food was found and life and culture was had.

“Especially because as a young man he actually drank from these rockholes as a man, my age, was walking around the Spinifex desert.

“And drank from that rockhole as a Tjitji (child).”

Mr Rictor, the youngest of three boys, only knew members of his immediate family until he was 21-years-old when he came across a group staying on Spinifex Country in 1986.

Up until this moment he had traditional hunter-gatherer in the desert with no knowledge of the colonisation of the rest of the continent, with the rest of the Spinifex people leaving the area 30 years earlier due to British atomic testing.

But given the international media hysteria following the emergence of the Pintupi Nine — who lived in the Gibson Desert until 1984 unaware of European colonisation of Australia — the Spinifex people have chosen to protect the Rictor family by restricting information about their experience of first contact.

Nearly 40 years later, and Mr Rictor remains cautious about opening up about this story, instead showing the pride of his country through his award-winning painting.

“It’s deceivingly beautiful country: red sands, white marble gums that grow out of the dunes,” Mr Adams Brown said.

Mr Rictor said he would use the $100,000 prize money for a new car, and a television while also helping him support his unwell partner.

“Tjuntjuntjara is very remote, it was a 25 hour car ride just to get to Alice Springs to catch the flight to Darwin,” Mr Adams Brown said

For Mr Rictor’s family, painting has been a point of celebration and power, with his brother’s paintings of birth sites used as part of their communities legal case for Native Title control of their lands.

“Noli saw those old people painting, and how much change it can bring, so then he started painting,” Mr Adams Brown said.

For Territory artist Wurrandan Marawili the call for land rights — particularly in his Blue Mud Bay home — was the clear truth hidden beneath the surface of First Nations art.

The Yolngu man from Yirrkala won the bark painting award for his piece ‘Rumbal, the body/the truth’, which depicts mangrove leaves covering the surface of the water while something lurks underneath.

“The mangroves, there’s something in there hiding underneath what you can see — but I can,” Mr Marawili said.

With a smile, Mr Marawili reveals the image beneath: “The lightning snakes”.

Tracing the hidden image of the twisting Mundukuḻ, Mr Marawili said: “It tells me the story yo. What’s in the sea, inside on the saltwater where I come from in Blue Mud Bay.”

Wearing the flag of his Saltwater country on his chest, the Territory artist said much like the lightning snakes the story of Sea Rights both obvious to Yolngu while being hidden from others.

The Territory dad said the painting took months to complete, slowly applying the earth pigments to the wood using a marwat, a brush made from strands of hair from his family members.

Mr Marawili said the award-winning painting was a continuation of his late-father’s legacy, with Bakulaŋay Marawili himself a great artist.

“My father taught me how to do this, he gave me everything for my future and for my little girl with me,” Mr Marawili said.

“(My father said) When I go, when I pass away then you can step up to my (role) … now I’m here.”

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Art and Material Culture curator Rebekah Raymond said she hoped people would feel “proud” and “open” seeing the collection of 72 artworks, with stories from around Australia.

“When I’m curating I’m thinking about how the works talk to each other, because they each have a beautiful story and they’ll have different conversations happening,” the Arabana, Wuthathi, Kala Lagaw Ya woman said.