How to keep top tech talent in Australia and the stop the US poaching our best ideas

There’s no lack of start-up innovation in Australia, but tech founders and emerging stars on The Australian’s Top 100 Innovators list reveal the big change needed to stop them from leaving home soil.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

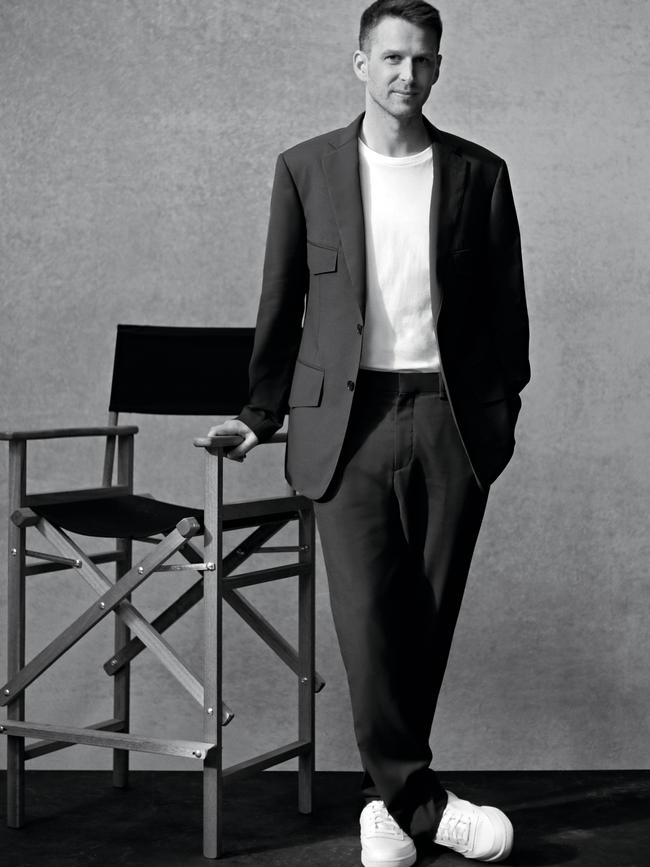

Craig Piggott is among a new group of entrepreneurs opting to seek out sophisticated capital at home. It’s a big shift from the days when founders automatically looked overseas for start-up support. Indeed, for most, going global has been the ticket to gaining serious funding for their projects. They have found the cash, but it is a strategy that challenges our ability to hold onto our talent.

Piggott stayed put in Auckland. Not only has he secured almost $70m from venture capital firm Blackbird, which described his company, Halter, as the “Nvidia of agriculture”, but he also plans to use New Zealand’s largest city as the springboard to take his business, now valued at around $330m, to the world.

After all, it was New Zealand that inspired him to create Halter, which produces smart collars for cattle.

This is an article from The List: Innovators 2024, which is announced in full on October 18.

“I grew up on a farm in the Waikato district of New Zealand, so I guess that was probably the important starting point,” Piggott says. “I had empathy for farmers. I felt that it was a really important industry and was underserved. There aren’t that many companies trying to really innovate in agriculture.”

With a background in mechanical engineering, Piggott concedes he initially didn’t know much about starting a company, building a team or raising money. He simply focused on making a product that creates virtual fences, allowing farmers to better monitor their pasture and shift livestock with the swipe of a finger on a smartphone.

Halter has since launched in Australia, where Piggott is seeking to shake up the $33.8bn livestock market, as well as in the US. He’s now eyeing a European expansion.

For Blackbird, it was a no-brainer to invest in a company claiming it can boost a farmer’s revenue by up to 30 per cent. “There are other companies making graphics chips, but really, Nvidia is the player. And that is kind of the similar thing for Halter,” says Blackbird partner Samantha Wong.

Still, as Titanium Ventures managing director Matthew Koertge says, the pull for Australian and New Zealand founders to physically relocate overseas to secure funding remains particularly strong as they attempt to overcome the constraints of being propped up by the three Fs: friends, family and fools.

Indeed, a study from Airwallex of 500 Australian founders revealed 40 per cent were accessing capital from the “bank of mum and dad”. But 78 per cent said they planned to expand globally in the next 12 months. This is not surprising if you look at the strategy of many VC firms. Koertge, who has co-helmed Titanium – formerly known as Telstra Ventures – with co-managing director Mark Sherman, has developed a recipe for success, with $1.35bn funds under management.

“We look for a large global market that is attractive and growing,” Koertge says. “We look for product market fit, so typically we don’t invest in pre-product, pre-revenue start-ups. We want to see a company has already got some customers and has some sort of product leadership and relevance and appeal to customers.”

Australia recorded 91 venture capital deals worth $US700m ($1.04bn) in the second quarter of this year, according to CB Insights. This compared to US figures of 2419 deals worth $US39bn ($57bn). Europe, meanwhile, recorded 1522 deals worth $US14bn ($20bn).

“The Australian market is a small market,” Koertge says. “There are some fantastic entrepreneurs here, but it’s a big world and the venture industry is competing more and more at a global level. Certainly, returns are more and more focused on a global basis. All these factors play significantly to entrepreneurs being funded or not funded.”

But going global does not necessarily mean a full relocation, thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic. Lockdowns and travel restrictions – and their hangover: remote working – have shown a business can be run from anywhere.

In a way, it represented a validation of sorts for Australian software giant Atlassian, which has long advocated for a distributed way of working and demonstrated entrepreneurs don’t have to leave the country to build global businesses.

Atlassian chief of staff Amy Glancey says founders Mike Cannon-Brookes and Scott Farquhar (who stepped down as co-CEO in September, remaining as a special adviser) didn’t want to “follow the Silicon Valley playbook” when they created Atlassian more than 20 years ago, choosing to stay in Australia.

But that decision had its challenges. “They speak about their early days and their journey being somewhat, at times, lonely,” Glancey says. “The two Aussies trying to build a global tech company on their own, without deep networks here in Australia, without a community, certainly without a ‘centre of gravity’ that they could go to every day and talk to people and have mentors.”

Cannon-Brookes and Farquhar are now seeking to build their own Silicon Valley-like hub, known as Tech Central, in Sydney, to create something they wish they’d had when they founded Atlassian. The $1.4bn development near Sydney’s Central Station has been almost a decade in the making, and is set to be completed in 2027.

Says Glancey: “When we think about bringing world-class, world-leading talent to Australia, and that big global talent coming here … They can look on a map and say, ‘Yeah, there’s this amazing global tech precinct in Sydney, and there’s real estate and it’s activated, and there are great education pathways.’ I do believe it will be a significant accelerator and continue to bring to life the industry.

“To have co-working spaces and start-up hubs, and then be right next door to Atlassian, where you get to bump into someone at the coffee cart and make a connection who will introduce you to a VC, it has so much texture, which is hard to describe until we’ve got it.”

Glancey says staying in Australia to build a global business also helps ease the stress that can steer entrepreneurs’ attention away from growth.

“[Relocations] are time-consuming, they’re costly, they take your energy and your brainpower away from the thing you’re trying to build because you’re distracted: ‘I need to get talent here, and I need to build a network, and I need to move my family, and I need to get new employment status and visas,’” she says. “[The pandemic has] shown the whole world that you can work effectively in a highly distributed, global, online way. That accelerated a decade’s-long worth of transformation of how knowledge workers work every day.”

Melbourne is also building its own tech hub, which has earned the nickname Silicon Yarra, at former warehouses in Cremorne, in the city’s inner south-east. It is now home to REA Group, Seek, Carsales.com.au and more tech companies.

On the other side of the city, Australia’s biggest health company, CSL, opened its new headquarters last year. It also houses an incubator for 40 biotech start-ups. CSL will share its knowledge of scaling up and running crucial tasks, such as clinical trials, to help more founders build global businesses in Australia.

CSL chair Brian McNamee says industries thrive amid competition, with “world-class regulators”, industry and academic collaboration, and full-scale capabilities.

“I would love to see more advanced manufacturing companies at the top of the ASX, another CSL. Multiple CSLs even,” McNamee said after the opening. “That means Australian companies take Australian skills, technology and innovation to the world.”

But Damian Kassabgi, chief executive of the Tech Council of Australia, says ensuring “proper capital allocation” locally is key to keeping more entrepreneurs in the country. He suggests regulatory changes to superannuation to bolster investment. “We think the climate is moving in a positive direction,” he says.

Kassabgi notes two big businesses – PsiQuantum and Afterpay – whose histories might have been different if there had been more money around. (Psi’s founders left the country, but have now received multimillion-dollar government backing for a controversial project here.)

Says Kassabgi: “The founders of Afterpay will tell you that if there was a pool of money to keep Afterpay going, they would not have listed on the ASX as early as they did. They would have kept the organisation private to focus on growth as a business, rather than being distracted by public markets in the early stages of the business.” (US-listed Block took over Afterpay for $39bn in 2022.)

Michael Batko, who has spent most of his career working in fast-growing start-ups, including freelancing tech company Expert360 and online pet marketplace Mad Paws, believes government can help, not only with funding but also policy.

“Australia already boasts an incredibly supportive infrastructure for start-ups,” he says, “and, in many ways, the best thing a government can do is to get out of the way of founders building businesses by streamlining processes and reducing unnecessary obstacles, rather than doing more.

“Simplifying early-stage requirements, such as getting a company started and ESOP (Employee Share Option Plan) regulations, would have tremendous long-term effects, allowing entrepreneurs to focus on building their companies without getting bogged down by red tape.”

Batko says the government can add value in three areas. The first is taking a top-down approach by matching VC commitments through initiatives like a “fund of funds”, which is an “essential feature of a mature ecosystem that Australia still lacks”.

The second approach is from the bottom up. Batko says this can be achieved by embedding entrepreneurship as a viable career path for teenagers and university students, fostering a self-starter mindset from an early age. Starting your own business needs to become a cultural norm rather than the exception, he says.

“Finally, if the government is going to invest directly in start-ups, it must ensure a consistent, long-term grant process,” Batko argues. “The constant cycle of start-up programs that appear promising but then vanish a few years later has been a significant source of frustration and wasted time for founders.

“Consistency and support across these levels will help set up more Australian entrepreneurs for success and keep them rooted in Australia, where they can contribute to strengthening our start-up ecosystem.”

Originally published as How to keep top tech talent in Australia and the stop the US poaching our best ideas