The Bloody Code: The worst ways to be executed in Britain in the 18th Century

Beginning in the 17th Century the Bloody Code consisted of more than 200 offences; a list of crimes that were punishable by death.

If you were a criminal in the times of the Bloody Code, it’s highly likely you’d be executed, whether you committed a murder, stole a rabbit or managed to wreck a fishpond.

Beginning in the late 17th Century the Bloody Code consisted of more than 200 offences; a list of all the crimes that were punishable by death.

In 1688, the number of crimes carrying the death penalty was 50. By 1815 there were 215 crimes on the list.

Why was the English legal system so brutal? It was mostly due to the wealthy men who created the laws; they looked down on everybody else as being lazy, sinful and greedy.

Judges rarely showed any mercy and, because the rich made the laws, they were created to protect them — any crime against their property was made punishable by death.

RELATED: Australia’s tragic beginnings: The grotesque story of the Second Fleet

RELATED: First mobile phone: World’s first call was an epic brag

RELATED: Mary Queen of Scots: Inside her gruesome beheading

The Bloody Code was thought to be a perfect deterrent and those times saw an increase in the number of public hangings. It was also thought that the more people witnessed public executions, the more likely they’ll be obeying the law.

Thankfully there were a handful of reformers, led by Sir Samuel Romilly, who were horrified that people could be executed for petty crimes.

It was 216 years ago this month that the dreaded ‘Bloody Code’ was revised by Sir Romilly and ensured people weren’t executed for cutting down trees, wearing blackface at night or impersonating a Chelsea pensioner.

Crimes on the Bloody Code

If you committed a crime that was listed on the Bloody Code — that’s 214 crimes on the list — chances are you’d be given a date to meet the hangman. Here are just some of the crimes you’d be hanged for:

• Stealing from a shipwreck

• An unmarried mother concealing a stillborn baby

• Forgery

• Impersonating a Chelsea pensioner

• Begging without a licence if you’re a soldier or sailor

• Stealing horses or sheep

• Arson

• Being out at night with a blackened face

• Strong evidence of malice in children aged 7-14

• Cutting down trees

• Destroying turnpike roads

• Wrecking a fishpond.

• Stealing from a rabbit warren

• Writing a threatening letter

According to historian Lizzie Steel, the main aim of the Bloody Code was deterrence. The other issue that made the Bloody Code so cruel was that those in court faced with this brutal system had to defend themselves. Once you were convicted, there was very little hope.

Let’s take a look at the most popular ways to be executed.

Hanging

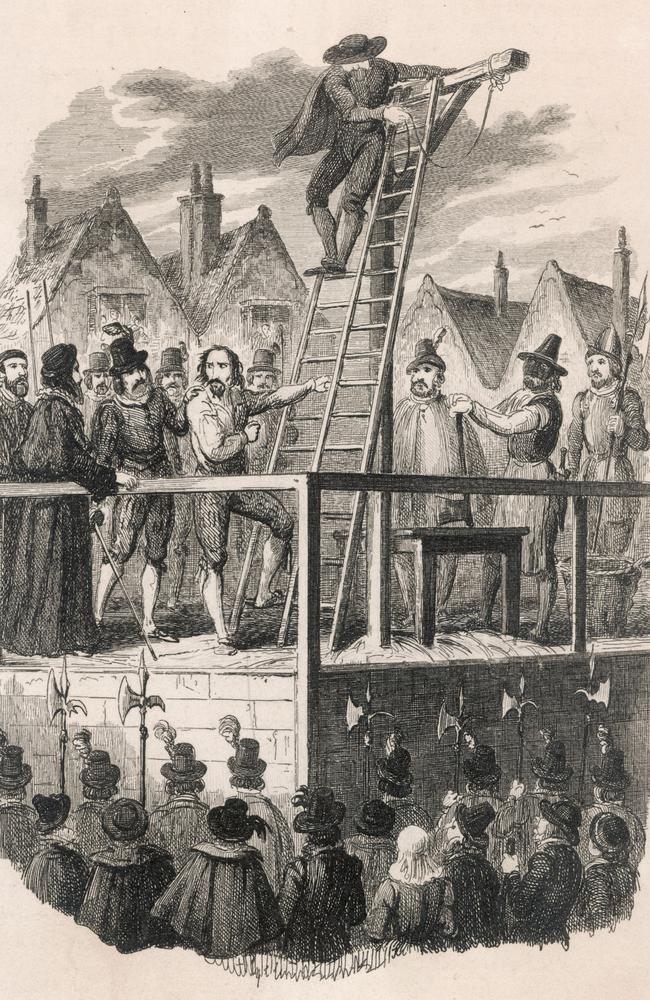

In the early years, hanging simply involved placing a noose around the criminal’s neck and suspending them from a tree. Other methods included using ladders or carts to hang people from wooden gallows. But by the late 13th Century the horrific practice of “drawing, hanging and quartering” was introduced. This was a death mostly reserved for those accused of treason.

First, the criminal was dragged by horses to the place of execution (drawing) then they were hanged, and then came the worst of all; the”‘quartering”.

The poor victim was disembowelled and beheaded and then their limbs were chopped off. Later, the head and limbs were kept on display for everyone to see — as a grisly reminder of what happens when one is foolish enough to break the law. Death was by asphyxiation, which was often excruciatingly, painfully slow.

According to historian Lizzie Steel, in 1783, the “New Drop” gallows were introduced, so that up to three criminals could be hanged at the same time. This involved a wooden platform with trapdoors through which the people fell.

The system of hanging was “upgraded” yet again in the later 19th Century when a “long drop” was used. This form of hanging took into account the prisoner’s weight and the length of the drop through the trap door. Placing the knot of the noose in a particular way meant that the criminal’s neck was broken, which was much quicker than being strangled.

Note: In 1752 a new law was created that meant the body of an executed person must be handed over to doctors for them to dissect, for the purpose of research. These days, that seems perfectly feasible but, back then, the idea of having their body cut up and used for research was truly horrifying. For most people, this new law was seen as an additional punishment to the execution itself.

Burnt at the stake

From the 11th Century, burning at the stake was used in England mostly for heresy and later (the 13th Century) for treason. The majority of those burnt at the stake were women who had been convicted of murdering their husband or employer and the practice continued in Britain well into the 18th Century.

The concept of burning at the stake was relatively simple. All that was needed was a pile of wood and a stake in the middle to tie the criminal to — then the fire is lit and life is over.

But death didn’t come quickly. It rarely took less than half an hour before the victim died and it often took up to two hours for the victim to die.

If it was windy and the fire blew away from the person at the stake, it could take hours to be slowly burned to death.

Hanging widely replaced burning for treason from 1790. However, women suspected of witchcraft in Scotland were still burnt at the stake until the 18th century.

Interestingly, if you were found guilty of a crime on the Bloody Code and were able to prove that you had basic literacy, you could claim “benefit of clergy”, which was available until laws were changed in the 1820s.

Drowning

Drowning wasn’t used as an execution but was used as torture to extract information which usually led to their execution. Of course, if people were accidentally held under water for too long, they’d inevitably drown on what was known as the “ducking stool”. This stool was just a seat on a long wooden arm. What did you need to do to be forced upon the ducking stool? If you’d been accused of spreading rumours, otherwise known as gossiping, you’d be ducked in the local pond or river until you confessed. 1809 was the last year the ducking stool was officially used as punishment in Britain.

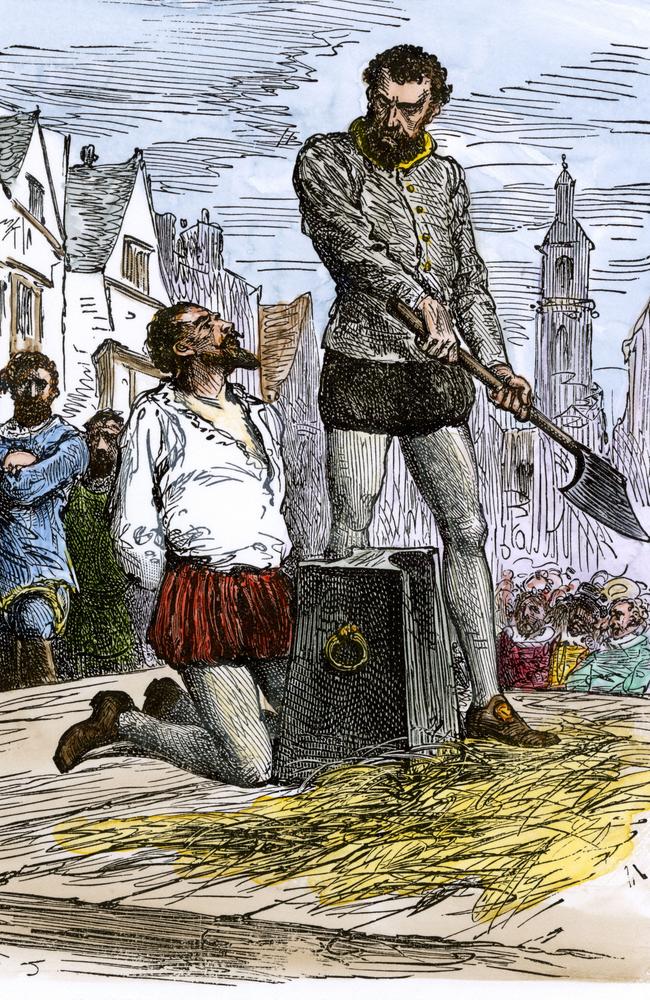

Beheading

You might think beheading might be less horrendous than a hanging but, due to the execution being carried out with an axe or a sword, it was often the worse of the worst ways to die. That’s because you might be unlucky enough to have an executioner who wasn’t entirely skilled in the art of swinging an axe against the nape of a neck and he might have needed several blows before your head was severed.

Beheading was usually reserved for the upper class because it was seen as being more dignified than a public hanging. Back in the 16th Century, during the execution of Mary Queen of Scots, it took three blows of the axe before her head was removed; it was said to be hanging by a “few strings” and witnesses said her lips were still quivering for a few minutes after her death.

Sir Samuel Romilly

One of the most vocal critics of the Bloody Code was the campaigner and reformer Sir Samuel Romilly, who protested against what many considered “a lottery of justice”.

There was such complexity around sentencing and punishment that, even when somebody was sentenced to death, there were often questions over whether that person was going to be executed immediately, sometime in the future, or not at all.

Sir Romilly, who was a barrister by profession, believed judges held too much power and would often sentence people according to their own beliefs.

After much campaigning, Sir Romilly succeeded in repealing the death penalty for some minor crimes, as well as ending the sickening practice of disembowelling convicted criminals while alive. By 1834, the practice of hanging in chains was abolished and there was an end of capital punishment for cattle stealing and other minor offences.

By the 18th Century, the more brutal punishments of the Tudor period were almost entirely abolished, although the public whipping of women didn’t end until 1817.

Macabre punishments, such as ear slicing and nose slitting also ended. The use of the pillory, a medieval torture device, stopped too — mostly because some people lost an eye or died while strapped into the wooden device.

LJ Charleston is a freelance historical journalist. Continue the conversation @LJCharleston