Australia’s tragic beginnings: The grotesque story of The Second fleet

By the time these ships began arriving in Sydney, most people couldn’t stand upright. Some had gaping wounds so deep you could see their bones.

When the first ships from the Second Fleet arrived at Port Jackson, NSW, in June 1790, those excitedly waiting on shore for the new arrivals were greeted with a horrifying sight – dead and dying men, shocking evidence of abuse, rampant disease and starvation.

Few men could stand upright and those that couldn’t crawl to shore were flung like sacks of flour overboard.

Witnesses reported seeing men with gaping wounds so deep from wearing irons for the duration of the voyage, you could see their bones.

Many of those struggling to reach the shore were close to death.

Dysentery was rampant. Onlookers were shocked to see men with bloated stomachs, bent over with painful cramps, others with legs that were swollen and purple, others barely clinging to life with blacken gums and loose teeth, grimacing in agony with scurvy.

Stories quickly spread about the cruel use of irons, convicts concealing deaths of their mates so they could use their rations and starving men forced to eat oatmeal poultices from dead bodies, (a poultice was used to help cure infection).

Those that survived the brutal voyage were so weak and ravaged by disease – adding extra pressure to a colony already suffering the effects of dangerously low supplies – up to ten people died per day in the week after their arrival.

This November marks the 227th anniversary of the trial of those responsible for the horrific abuse and loss of life onboard the ships - it’s a story of abuse many Australians today are completely unaware of.

Added to the mix was a group of selfish contractors’ intent on cutting corners, a captain so paranoid about security he refused to let convicts up on deck for fresh air and another captain whose previous job had been overseeing slave ships.

Here’s a moving account by the First Fleet’s Chaplain, Reverend Richard Johnson, who witnessed the landing of the Second Fleet from 26–28 June, 1790.

“I beheld a sight truly shocking to the feelings of humanity, a great number of them laying, some half, others nearly quite naked, without either bed or bedding, unable to turn or help themselves.

“Spoke to them as I passed along, but the smell was so offensive that I could scarcely bear it…. The landing of these people was truly affecting and shocking; great numbers were not able to walk, nor to move hand or foot; such were slung over the ship side in the same manner as they would a cask, a box, or anything of that nature.

“Upon their being brought up to the open air some fainted, some died upon deck, and others in the boat before they reached the shore. Some creeped upon their hands and knees, and some were carried upon the backs of others.”

The First Fleet arrived in NSW with a mortality rate of 5.4 per cent.

The Second Fleet arrived in NSW with a mortality rate of 40 per cent.

It’s no surprise the Second Fleet was known as ‘The Death Fleet.

*****

The Second Fleet consisted of six ships which were sent to the newly established colony of NSW in 1789–90. The First Fleet, which departed England in 1787, had done little to reduce London’s huge prison population.

So, once word was received from Governor Arthur Phillip that the colony of NSW had survived, the decision was made to send the Second Fleet – the Scarborough, Neptune, Surprize, Justinian, Guardian and the Lady Juliana.

But the voyage was a total disaster.

Of 928 male convicts on Neptune, Scarborough and Surprize, 26 per cent died on the voyage and nearly 40 per cent were dead within months of their arrival in the colony. This shocking mortality rate was nearly ten times that of the First Fleet voyage.

What went so horribly wrong?

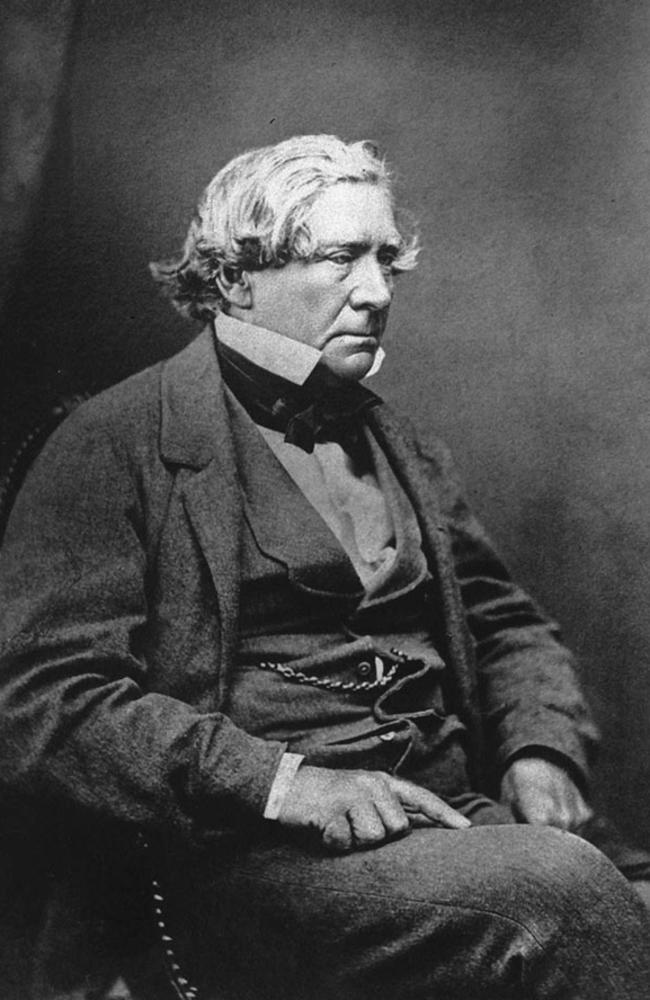

Historian and author of The Second Fleet: Britain’s grim convict armada of 1790, Michael Flynn, told news.com.au the First Fleet convicts had it easy compared to the horror experienced by the Second Fleet.

“The major difference was that the First Fleet was closely controlled by the British government and transports were monitored by Governor Phillip and his two naval ships the Sirius and the Supply.

“As a result, it was very expensive, and, for the Second Fleet, the British government decided to take on contractors who totally botched the voyage,” Flynn said.

“The First Fleet stopped three times along the way, so people were able to get fresh food and water, which made a huge difference. But, for the Second Fleet, the private contractors cut corners and only stopped once, at Cape Town, South Africa.

“The captain was very security conscious and kept the convicts below deck for a long time in bad weather. It would have been horrific as the ships were over crowded.

“The Second Fleet was combination of bad luck, mismanagement and wishful thinking in terms of being able to do the voyage on the cheap.”

The Second Fleet was a grim example of privatisation gone wrong in the most catastrophic way.

The First Fleet was an expensive exercise for the British government. When planning stages began for the Second Fleet, the government’s penny-pinchers set up bidding for the contractors to be on a fixed-price per head basis, with the contract to be given to the lowest bidder.

But payment wasn’t dependent on how many people reached Australia alive.

Most contractors refused to take that risk because, in those days, low standards onboard meant high death rates. Instead, the contractor was paid for the number of people who boarded the ships in Britain. In other words, there was absolutely no incentive for the contractors to treat the prisoners with care.

There was also a provision in the contract, allowing contractors to sell any leftover provisions at the end of the voyage. This saw the ruthless captains reportedly withholding food from the prisoners which they later sold “for a killing” to those struggling in the colony of NSW.

Overall, 267 people died at sea and at least 150 died shortly after arrival.

The worst ship of all was the Neptune. Of the 499 onboard only 72 arrived in reasonable health. 158 died; 269 were incapacitated at the time of landing.

William Hill was a second captain in the New South Wales Corps who sailed with the fleet. He told officials conditions in the slave trade were better than the Second Fleet. He wrote about the masters of the Neptune and the Scarborough, as being cruel men.

“The more they can withhold from the unhappy wretches, the more provisions they have to dispose of on a foreign market, and the earlier in the voyage they die the longer they can draw the deceased’s allowance for themselves; for I fear few of them are honest enough to make a just return of the dates of their deaths to their employers.”

The ships set out for Australia in three stages, all arriving during June 1790, apart from the Guardian which had struck an iceberg in the Southern Ocean. This was devastating for the colony as the Guardian was filled with supplies such as stock and plants. (It eventually made it to Cape Town where it was beached).

First to leave England was the Lady Juliana with its ship load of women. This ship had the longest voyage (just over 11 months) but the convicts arrived in good health. In fact, a seaman who witnessed the ladies’ arrival wrote: “They were all fresh, well looking women”.

The arrival of the Lady Juliana meant the ratio of women in the colony went from about 20 per cent to 40 per cent. There were seven babies born on the voyage and many more shortly after they arrived, obviously, due to “shipboard romances”.

THE LADY JULIANA

The Lady Juliana left England on 29 July 1789, carrying about 230 women. There were only 193 women on the First Fleet and London’s Newgate Gaol was terribly overcrowded so it was decided that a ship load of women would go to NSW.

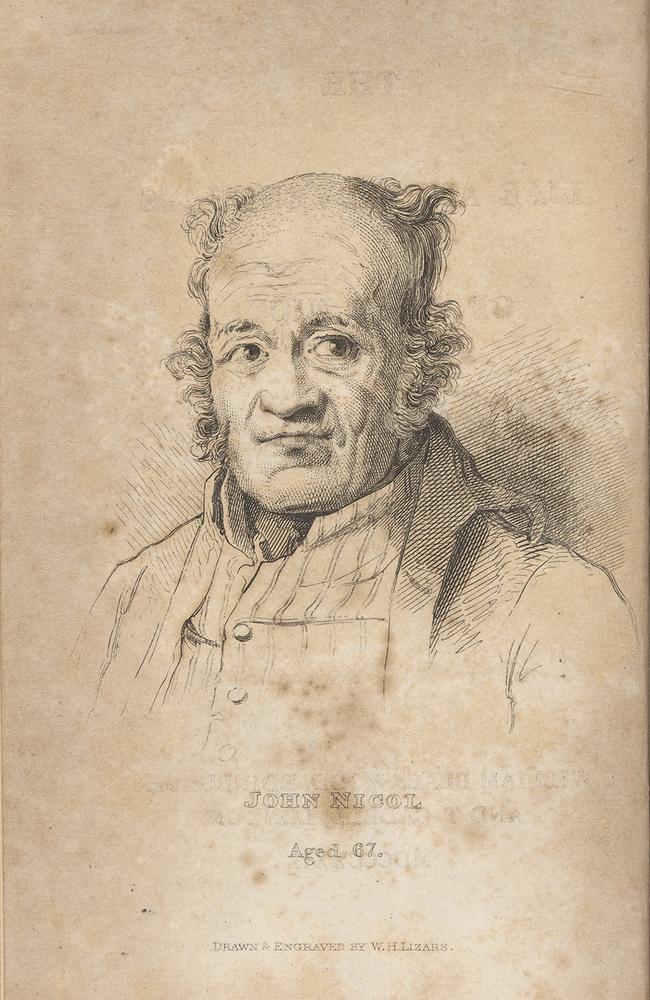

Ship’s steward Jon Nicol wrote about his time aboard the Lady of Juliana, stating that every man struck up a consensual relationship with a woman.

The ship took nearly 11 months to arrive in Sydney – compared to Surprize which took 158 days and Neptune, 159 days – leading maritime historian Charles Bateson to refer to the ship as “a floating brothel”.

A British newspaper reported: “The female convicts carried to Botany Bay, by the Lady Juliana transport, were delivered very soon after their arrival of thirty-seven children, the exact number of men in the ship!”

Another stroke of luck for the female convicts was that the Lady Juliana was forced to stop at three ports for repairs, so the women benefited from having fresh meat and vegetables.

According to historian Michael Flynn, many of the Second Fleet women mothered children who became important figures in NSW.

Catherine Crowley’s son, the future politician William Charles Wentworth, was conceived on Neptune with ship’s surgeon D’Arcy Wentworth.

But life was not so easy on the other ships.

SHIP OF HORRORS

In February, a rumour spread that convicts were planning to “rise up” and take the Scarborough. This led to a decision that all male convicts were kept chained up for long periods and rarely allowed on deck for fresh air and exercise. By the time the ships reached Cape Town on April 13, 68 men were dead.

According to Michael Flynn, any excitement at the arrival of the Second Fleet quickly gave way to horror. Governor Philip and his officials were deeply shocked at the sight of such gross inhumanity. Phillip immediately sent a message to the British Government to condemn the handling of the transportation.

Several of the Second Fleet crewmen had deserted and, as ships arrived in England from September 1791, British newspapers carried details of the horrendous abuse onboard.

By November, lawyer Thomas Evans, launched a private prosecution in London courts.

The Neptune’s captain Donald Trail, a former navy master who had commanded a slave ship and was described by many as a sadist, was brought to trial at the Old Bailey in the admiralty court – along with his chief mate William Ellington.

Michael Flynn said the trial was initially about unpaid wages for some of the seamen on the voyage, but the issue was raised about the brutal treatment of the convicts.

“But Trail and Ellington were acquitted in that trial and the government defended them when it was raised in parliament. By that stage, the international scene was lurching towards war with revolutionary France, so the Second Fleet faded into the background,” Flynn said.

“The same contractors did bring out the Third Fleet in 1791 but, by that time, there had been changes in contracts and policy as well as incentives that were used to encourage contractors to keep convicts alive by paying them bonuses – as a result of that the death rate was kept quite low.

“So, the Second Fleet deaths had one positive effect.”

Flynn believes it’s a shame the Second Fleet isn’t given as much attention as the First Fleet.

“The Second Fleet is overlooked and I think it’s important that people do know about Australia’s very tragic beginnings.

“Many people alive today are descended from the Second Fleet so it’s a major and brutal part of our history that shouldn’t be neglected,” Flynn said.

During his meticulous research, Flynn discovered that many of the convicts that died on the Second Fleet had been sentenced to death in England, but were offered a life sentence in Australia as an alternative to the gallows.

Many refused the offer, but some were persuaded by prison chaplains to board the boats. Knowing this, it’s impossible not to dwell on which death might have been less horrendous.

More than 200 years later, the monstrous story of the Second Fleet is still as shocking as ever.

— If you want to see if you’re related to one of the Second Fleeters, visit the State Library

— LJ Charleston is a freelance journalist. Follow her on Twitter @LJCharleston