Stasi document reconstruction team is painstakingly uncovering state secrets, piece by piece

It’s one of the most repressive and brutal regimes the world has known, now painstakingly low-tech work is bringing to light the full extent of the horror.

In a meticulous series of files housed in a building in East Berlin is a library of a nation’s hopes, fears and dreams.

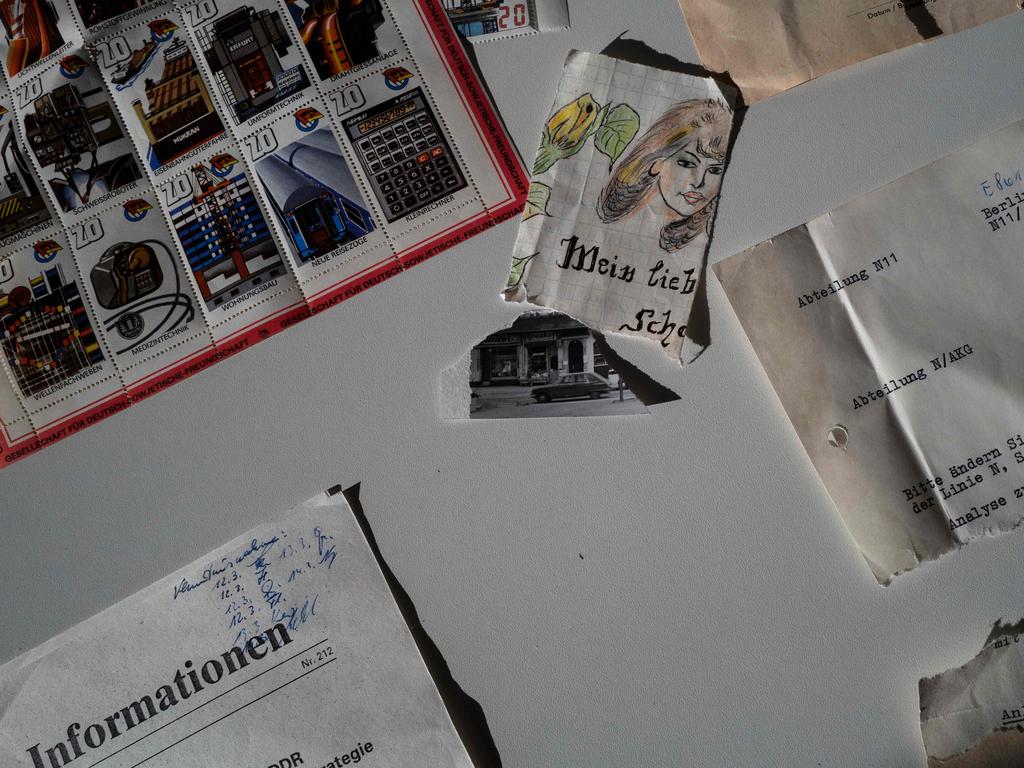

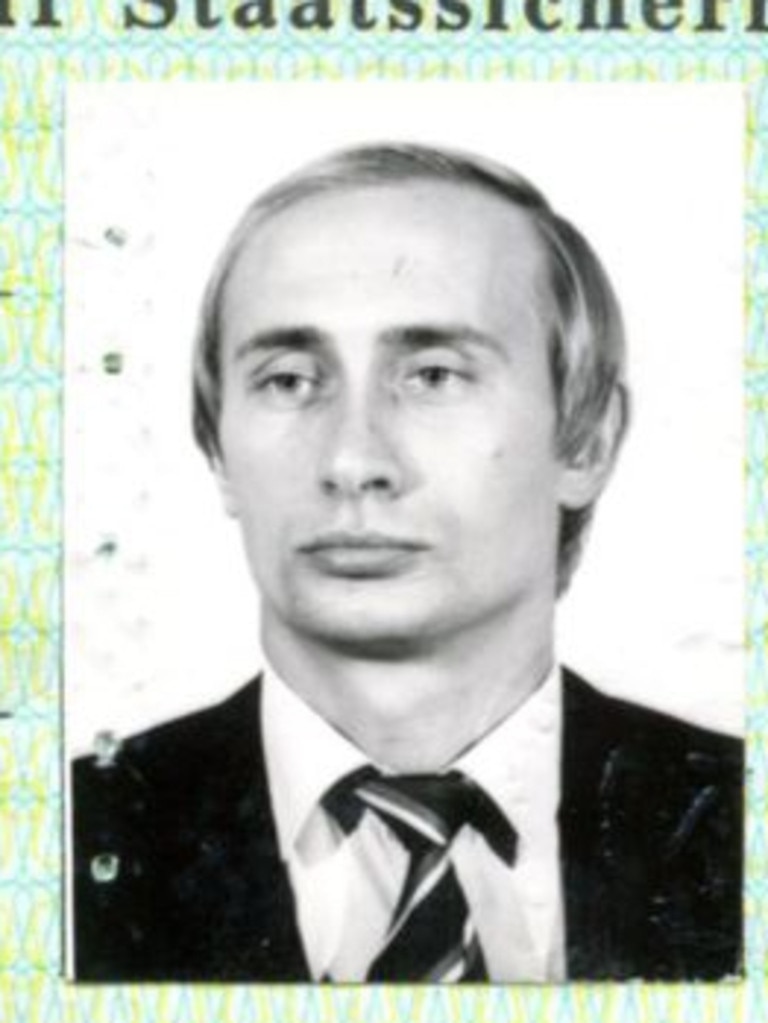

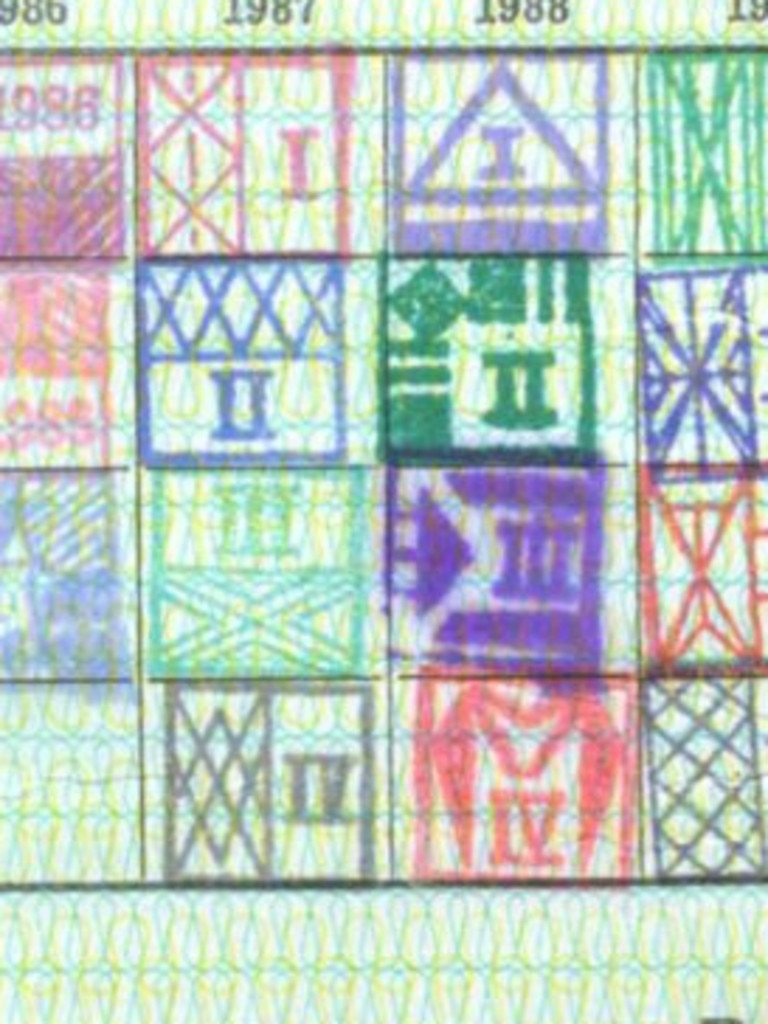

The archive of East Germany’s Ministry for State Security, the Stasi, stretches 111km and covers everything from the political leanings to secret habits of the former state’s citizens.

Far from being complete, the enormous trove is growing by the day thanks to the painstaking work of the document reconstruction team.

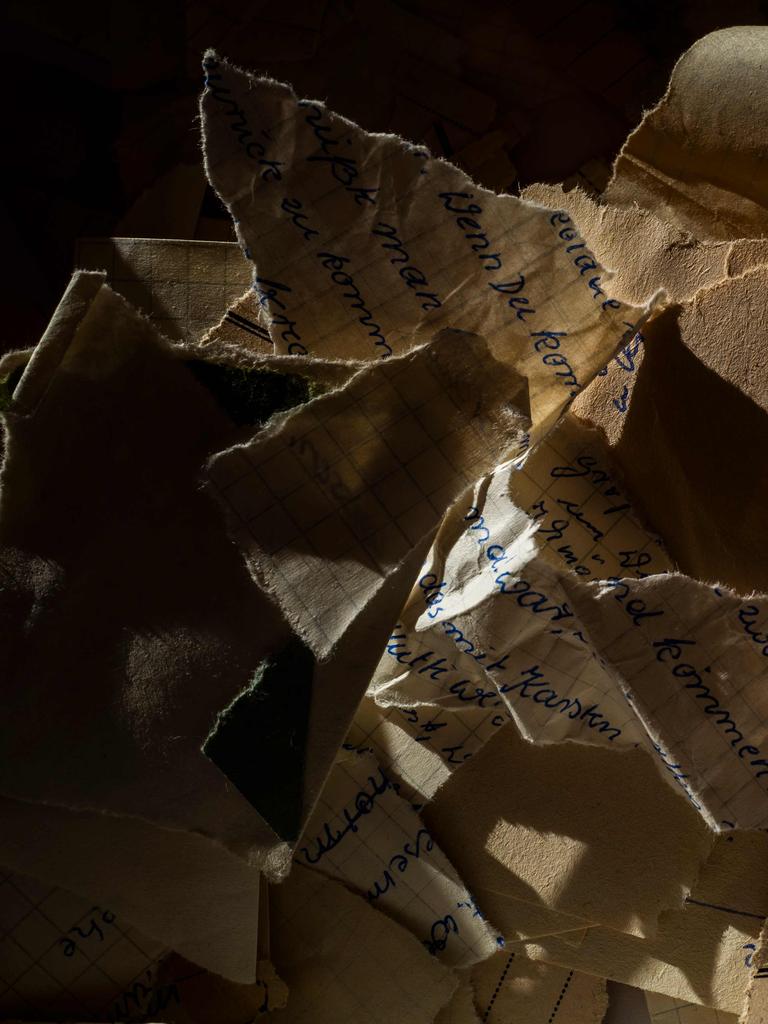

The 10-strong outfit is piecing together items shredded by the secret police in a desperate attempt to hide their work after the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989.

Archivist Barbara Poenisch, born in East Germany herself, is one of those tasked with piecing destroyed documents back together. Working by lamplight with paperweights, a scalpel and sticky tape, she told news.com.au it was “very satisfying” to put the ruined pieces back together.

“I knew this past. I want to contribute quite literally, to piecing it back together and making it available to future generations,” she said.

After she has puzzled out the documents, they will be filed and made part of the wider archive that reveals the true extent of the power the East German state wielded over its citizens.

“Even though the work looks not so challenging, the knowledge of what I’m doing here is very satisfying in that it helps broaden the knowledge base for the archive,” she said.

MORE: Berlin celebrates fall of the Berlin Wall

Information in the Stasi files underpinned the sense of absolute control the East German state had over its citizens, gathered through an extensive network of 91,000 full-time staff and about 180,000 unofficial informants.

Everyone from colleagues to lovers, neighbours to family members, was used to build up an elaborate picture of citizens and head off any threats to the regime.

Over time, Stasi strategies morphed from outright brutality and repression to “psychic demolition” – where rumours and manipulation were used to intimidate and undermine those deemed dangerous to the state – ruining their reputations, lives and careers with many victims never fully realising why.

In the autumn of 1989, the Stasi ordered the information destroyed with many files shredded, pulped and burned. However on January 15, 1990, protesters stormed the Stasi offices in an event known as the “storm on Normannenstraße” demanding the documents be saved.

Remnants of the archive were scooped up and placed into thousands of sacks.

Now, 30 years on from the fall of the Berlin Wall, work continues to piece the together the documents, which have revealed everything from statewide plots to heartbreaking human tragedies.

“You have to be ready to look in these files,” said Dagmar Hovestadt, head of communications for Stasi records.

She said interference and manipulation was the common theme among files, which can lead people to question “deep-seated assumptions about who they are”.

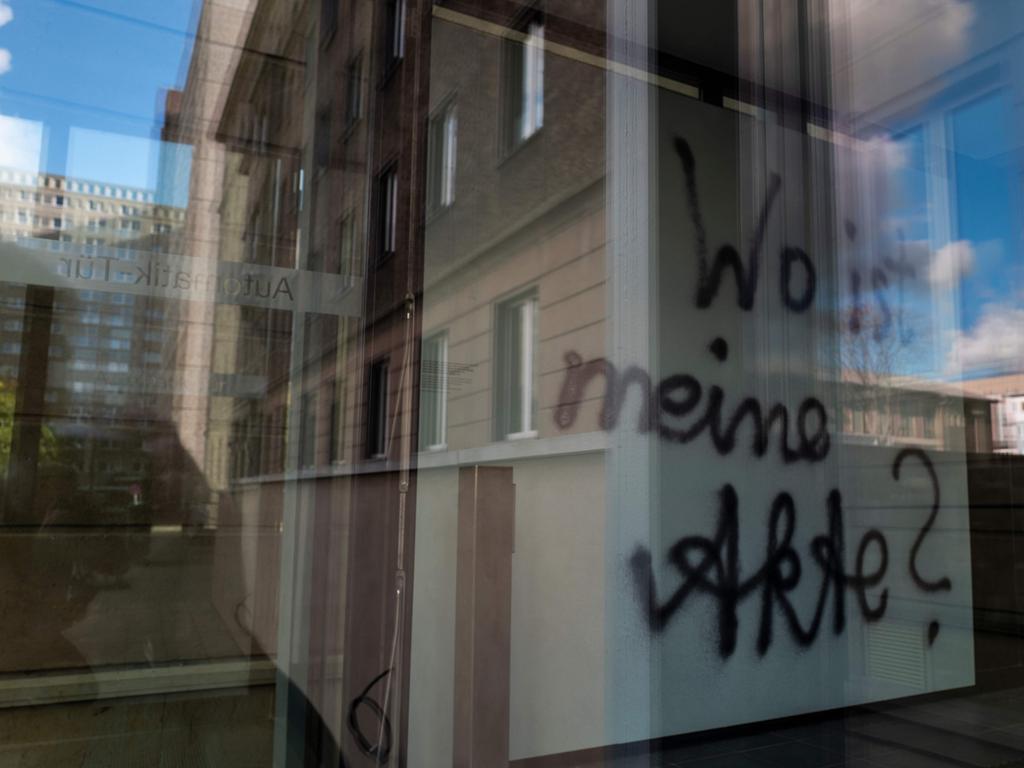

In the first two years since they were made available to the public, the office received one million requests for information. Now, it receives 4000 each month from those keen to know what information the state held on them.

For many, it’s led to huge revelations, such as finding out the reason they were stopped going to university or following a certain career path.

“It’s not because you’re not smart, but because the state says you’re not reliable,” Ms Hovestadt said.

“And the source for that information is pure suspicion. It could be a friend who said ‘yeah she’s not really into the party’ and that means you can’t go to university.”

“All these decisions are life changing. They are taking away your control over your life’s path, because of what the state decided to do.”

Reconstruction efforts have revealed everything from details of East German state-sponsored doping in sport to information about Red Army militants assigned new identities by the East German state.

They also show human tragedies and the extraordinary minutiae of life in the German Democratic Republic – a paranoid state that recorded observations on which way people looked as they walked past a sensitive military site.

For Ms Hovestadt, some of the most outrageous interventions include personal humiliations designed to undermine people’s confidence and sanity. A woman, for example, who had her bike tyres punctured regularly while at a weekend market. Or a couple caught trying to smuggle their children into the West who were made to recreate the scene for photographs.

“It’s how they want to live their life and how the state interferes with it or stops them from going to their full potential and leaves them stuck in their tracks,” she said.

Reconstruction team leader Andreas Loder, who has worked at the archive for five years, said there are “still new things to discover” in the information.

He recalled one particularly haunting case where a woman had sought the whereabouts of her husband who mysteriously vanished, only to find he had declared her dead and remarried.

For Mrs Poenisch, a moving letter from an elderly woman to ask for the freedom of her son to help her on the family farm struck a chord.

So far, 1.5 million pages of documents from 500 bags of shredded material have been reconstructed over 20 years. There are around 16,000 bags left, each of which contains between 2500 and 3500 shredded pages.

In 2013 hopes were raised that technology could help the process with an e-puzzler developed for the job. However the level of scanning sensitivity required proved too arduous to be efficient and only about 23 bags, or 91,000 pages were fitted together digitally.

There are still about 400-600 million fragments, representing 40-55 million pages that need to be worked through.

Now, a new machine is being designed and will hopefully be deployed in the coming years.

Ms Hovestadt said despite the scale of the task, the German government was committed to preservation of the archive, which provides an important insight into how state surveillance functioned.

“The fear that they were right there and they could reach out to you at any moment was a great tool,” she said.

“Ultimately it’s quite sad and a little overwhelming that your normal life and your desire to have free speech and political thinking resulted in this huge apparatus.

Despite the horrors contained within, she said the archive also contains a message for how we live now.

“You find courage in these files … you also see the frailty of people and the weakness,” she said.

“You are much more aware of how you want to live today and how valuable the rights are today.”