Celebrations and commemorations as Berlin remembers 30 years since fall of the Berlin Wall

A map of one of the world’s most famous cities from above contains glaring evidence that most people would rather forget.

Andreas Pfeiffer was nearly 14 and had never tasted Coca-Cola when the wall that divided his city came crashing down.

Now 42, the former national high-diver was deep into his training schedule, living with his family who were loyal to the East German government when the world began to transform around him.

On 9 November 1989, the young Andreas was asleep at home with his family and his parents didn’t mention the news – anxious as to whether the new-found freedoms could be real.

“They actually said nothing and even the day after that,” he recalled. “On Saturday I went to school in the morning and I came back and I was like ‘you know what? Everybody went to the West, what’s going on?”

Later that day, his parents bundled the young Andreas and his sister into their communist-model Trebby car and joined the procession flowing into West Germany, where elated Berliners doused their car in champagne and threw chocolates in the windows.

“I remember when we went over, even the smell was sweeter in the city,” he said. “There were so many lights. When we went to a big mall there were so many lights, so many things. I got headaches. For me it was a bit strange. Everything was so new and big.”

Like any young teen, what sticks most in his mind is “all the tastes” they soon found in the West.

“When you were growing up in the Eastern part, you just had two chocolates. There was one chocolate and another and that’s it and not like 275 chocolates,” he said. “We only had one cola. It was kind of an explosion” – he mimes the shock of something exploding in his mouth – “It was great. It came at a good time for me.”

On Saturday, Berlin celebrates 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall, a divisive symbol that loomed large over the city and is still evident from space due to the different coloured street lights used in East and West. It was erected on the night of 12 August 1961, taking residents by surprise when they woke up the next morning. In an instant, families, couples and colleagues were divided into East and West. Heartbreaking pictures from the time show parents holding their babies to show them to loved ones on the other side.

The wall was an attempt to stop people from the East German Democratic Republic (GDR) leaving for opportunities in the west, where a steady stream of emigrants was undermining East German propaganda. Initially made of barbed wire in parts, the wall proved porous and many escaped to the West by jumping out of building windows, making a run for it at the border or crossing the river portion of the border in bathtubs with children.

Over time, it became more heavily fortified, eventually turning into the 155 kilometre scar that zigzagged throughout the city, following divisions laid down by Allied powers after World War Two. The concrete blockade had a 10 metre wide “death strip” in the middle, illuminated with bright lights and ragged with barbed wire, where guards in watchtowers would sleep in shifts and shoot to kill anyone trying to cross.

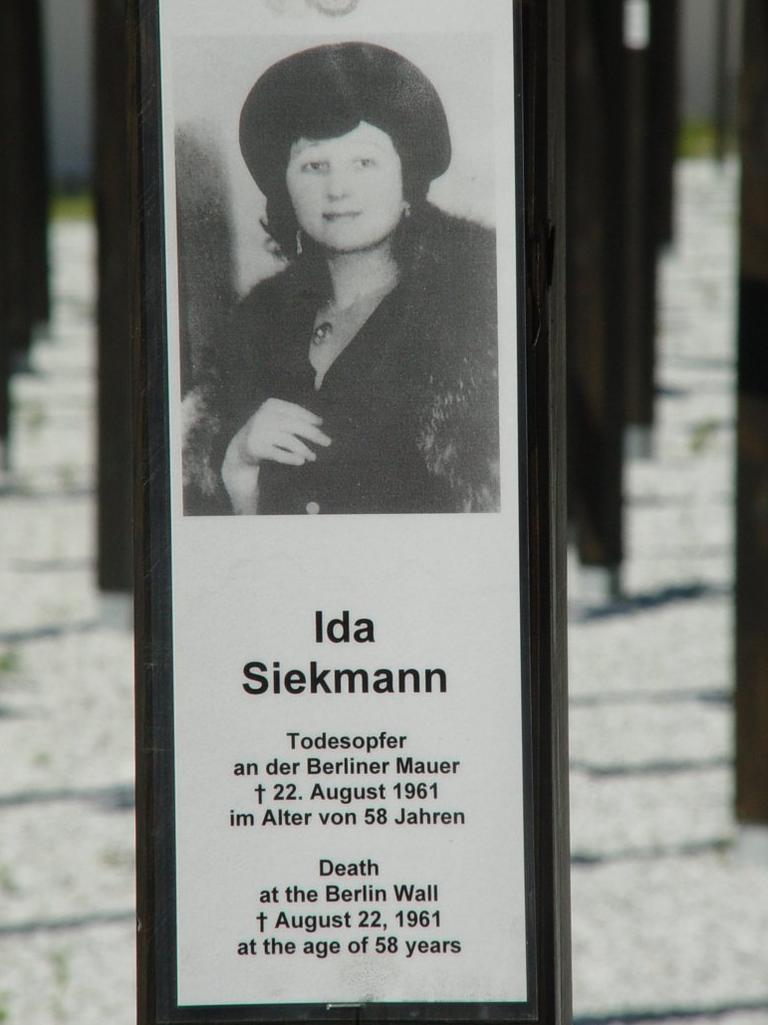

At least 140 people died at the border or trying to escape, with an unknown number of other deaths connected to the wall. The first known person to die was Ida Siekman, who lived in a building that straddled East and West in Bernauer Strasse. She had been cut off from her sister, who lived in the West and decided to try and escape out of her third flood window just ten days after the wall went up.

The East German police noted in a report that at 6:50am, Ida Siekman had tried to jump and “was carried away by the West Berlin fire department. The blood stain was covered up with sand.”

Other victims include two boys, Lothar Schleusener, 13, and his friend Jorg Hartmann, 10, who were shot 40 times in a hail of bullets by a guard who later said he was firing at shadows. Jorg had left the house to buy bread rolls and never returned, while Lothar had told his sister he would bring her back something nice from the West. Their deaths were covered up and recorded as an accident by East German police.

MISTAKE THAT CHANGED THE COURSE OF HISTORY

The wall remained in place for 28 years, with around 5000 escapes including some by astonishing means. People were smuggled in cars and crawled through tunnels under the city. One man crossed via a cable shot with bow and arrow into a building on the other side. Others swam the River Spree or tried via hot air balloon.

On 9 November 1989, “destiny was knocking”, as one German media network put it, and SED official Gunter Schabowski made a mistake that would change the course of history.

Earlier that week, the GDR had been rocked by the largest protests it had ever seen, with thousands filling East Berlin calling for democratic reforms. In response, four communist party officials were tasked with devising new travel laws that would let a little pressure out of the cooker – namely by allowing the dissenters to cross the border.

The new travel laws were written and handed to Schabowski for a press conference at Communist Party headquarters, who read them to a room full of press without checking the draft. Shocked at the changes, an Italian journalist asked when they would take effect. “As far as I know … as of now” came the off-the-cuff reply from Schabowski.

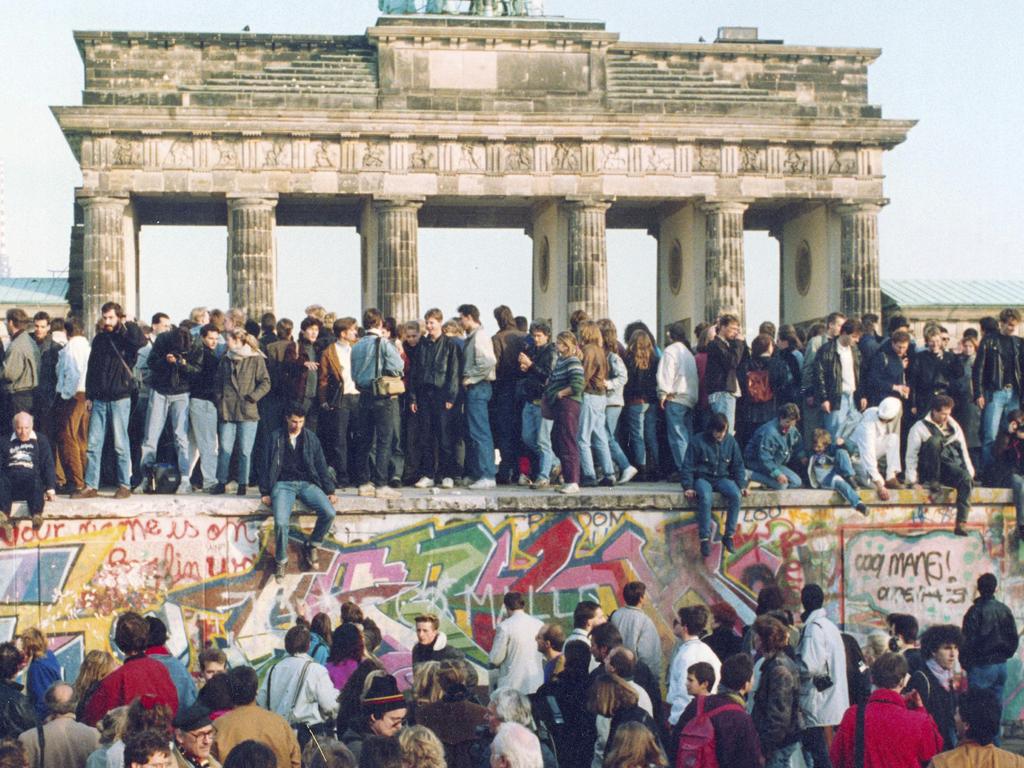

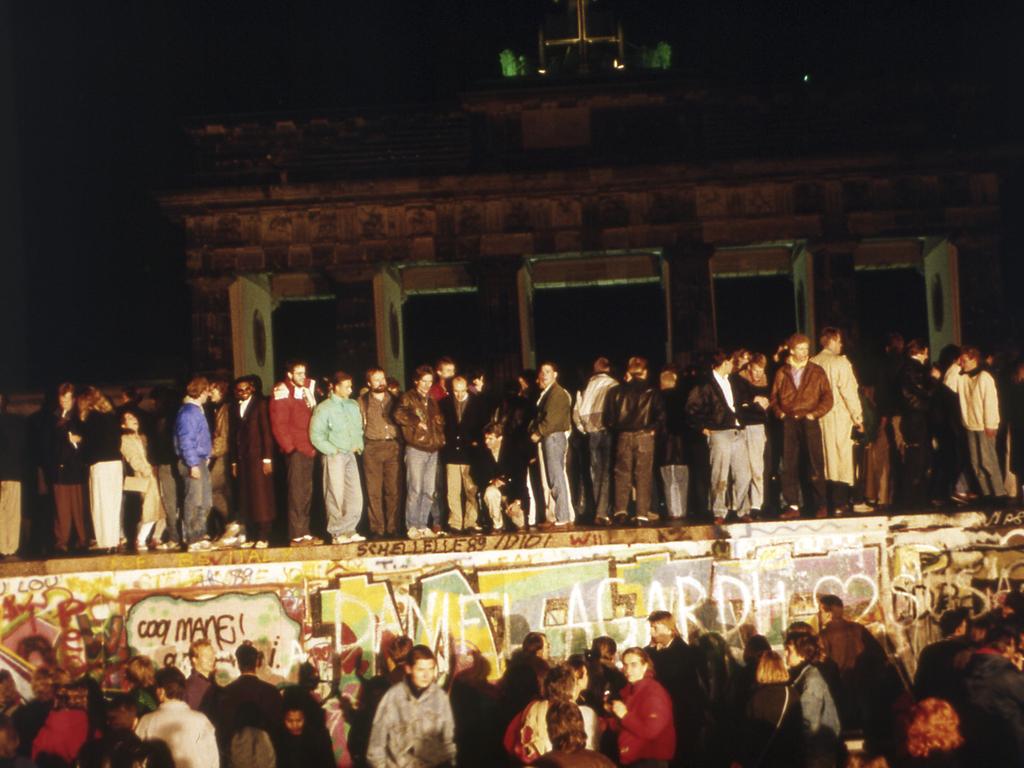

The news was instantly picked up by West German television networks and broadcast around the world. People flocked to the wall to see it for themselves and confused guards turned them away. But soon the trickle turned into a flood and people crossed the wall at Bornholmer Strasse. Now iconic scenes show thousands at the Brandenburg Gate, previously located in the middle of the death strip, where people chipped at the wall with hammers and chisels.

Locals have described the moment as the “happiest moment of Berlin history”. For Anna Dedorson, a Swedish tour guide who came to the city 12 years ago to live in its famous squatting scene, the atmosphere the wall created gives Berlin a unique sense of character.

“It affects the atmosphere of the city. It’s extremely tolerant, very open-minded,” she said.

“There’s a big vibe of why it’s so free and it’s because of the particular history. The distrust of the establishment is very high.”

This weekend, thousands will gather at the wall again at seven different venues around the city for a week-long festival to celebrate the 30th anniversary with events including everything from East-German punk bands to panel discussions. A flagship installation at the Brandenburg Gate, Visions in Motion, includes stories from 30,000 Berliners who have written messages of hope – many of which say “no walls” ever again.

“It’s inspiring to see what people did back then. They overcame their fear, they took to the streets. In the end they made the impossible, possible, said Simone Leimbach, project manager for Kulturprojekte Berlin who has been working on the project for 12 months.

She said the thousands of small actions which changed history in Berlin have given people strength for today’s challenges, in a world where nationalism across Europe is rising, Brexit is taking place and pro-democracy protests are raging in Hong Kong and Chile.

Yet despite the elation of that night 30 years ago, the story of German reunification has been a complex one with many former East Germans feeling their side of the country has still not caught up. Ms Leimbach said many East Germans feel people are “looking down on” their past, “but that doesn’t mean you didn’t have a happy life and great times,” she said.

It’s something German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who was also raised in the East and was in a sauna the night the wall came down, has acknowledged as recently as last month.

“Official German reunification is complete. But the unity of the Germans, their unity was not fully complete on October 3, 1990, and that is still the case today,” she recently said. “German unity is not a state, completed and finished, but a perpetual process.”

The feeling rings true for Andreas Pfeiffer who had a happy childhood with parents loyal to the GDR and was shocked to find out three years ago his father had plans to escape.

“He was quite unsatisfied and he wanted to get my mother over the border and then the kids after that,” he said, “There was already a plan but in the end he was too anxious and … he didn’t do it because he was afraid that something might go wrong.”

Back in 1989, after tasting chocolates in the West and having their car doused in champagne, the family returned home and resumed school and training as normal.

“You had actually a lot of things that were very good for kids and for young people,” he said about life in the East.

“I still think that it was a really good idea the socialism thing. It was a really good idea, because …. people helped each other. The people were closer.”

“The idea was good. But of course the men who were ruling the whole system weren’t good. And of course the whole Stasi thing was bad, but as a kid I didn’t know about these things, and for me, it was a good life.”

Continue the conversation on Twitter Victoria_Craw | victoria.craw@news.com.au