‘Below the replacement rate’: Alarming trend sweeping the globe

Humanity appears to be sliding into a terrifying “doom loop”, with experts warning of dire global consequences in the near future.

Is humanity sliding into a “doom loop”?

Unaffordable housing. Soaring costs of living. Inaccessible education. Coercive employers. Exorbitant childcare costs. A lack of hope for the future.

All contribute to a global malaise expressing itself in falling birthrates.

Many government policies designed to tackle these issues, ranging from imposing communal living on young families through to penalising single women, are making matters worse.

And that’s compounding what some experts believe is the underlying cause.

Most couples don’t want more than one child.

The 20th Century began with a population explosion. Middle classes were expanding. Health, housing and income were improving. Birth control was chancy – and often dangerous.

The 21st Century is a population tipping point. Financial inequality is returning to Medieval feudal ratios. Health, housing – and food – expenses are soaring. And birth control is often readily available.

“There’s been an entirely unanticipated acceleration of the already existing long-term decline in global fertility, more or less everywhere,” says American Enterprise Institute political economist Nicholas Eberstadt.

“It’s not impossible that the world has already fallen on a planetary scale below the level of child-bearing necessary for long-term population stability.

“We can’t tell if that’s actually happened yet. But if this has not happened already, it may happen much sooner than people expected.”

From boom to bust

In Mexico City, the trend is less than one baby per woman per lifetime.

Thailand is at about a one-to-one ratio.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) recorded a fertility rate of 1.5 for 2023.

“You need a little bit over two for long-term population stability,” Eberstadt told Foreign Affairs.

“Not just two, but a little over since not everybody survives to child-bearing years.”

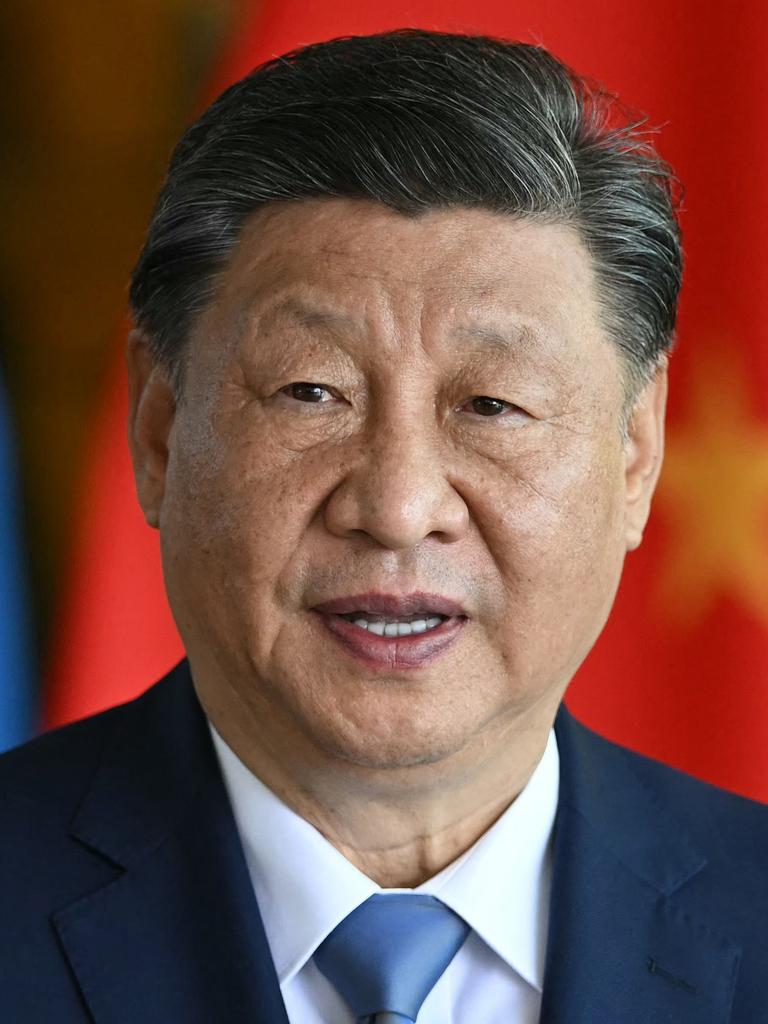

Even the world’s most populous countries – India and China – are below the replacement rate.

It’s a dramatic change that has been a single generation in the making.

“It is striking when you take a step back and look at the 20th century,” says Eberstadt.

“We began at around 1.6 billion people on the planet. We ended at 6 billion people, which is an enormous jump.”

Only the wealth generated by this surge of new taxpayers produced the scientific innovation needed to feed and care for burgeoning populations.

“What was missed by many during the Population Explosion panic was that this surge in human numbers was generated entirely by improvements in health – by pervasive plummets in mortality (and) by explosive increases in life expectancy,” Eberstadt observes.

More mothers survived childbirth.

More children grew into adulthood.

Life expectancy doubled.

But that growth lasted only one generation.

That one generation lived for as long – and was as productive as – two. Modern global economics, society and expectations were built by that generation.

And that will have overwhelming implications for future economics, industry, defence – and governments.

The housing shortage will plummet into surplus.

Employers will have to bid ever higher wages for scarce employees.

And an ever-shrinking pool of taxpayers will need to fund the (delayed) retirement of the elderly.

“You live in a world where there are five or six current earners for every retiree. That’s great. You’re getting social benefits on the cheap,” Eberstadt says.

“As soon as that population pyramid tilts, you’re in a doom loop. You just can’t do it.”

Paradise falls

Who’s to blame?

Is plastic injecting synthetic oestrogen into our food and water? Is it educated women? Is it the economic imperative for both parents to work?

“There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that the big declines in fertility we’re seeing yet are due to environmental factors,” Eberstadt observes.

“They do seem, for the most part, to be driven by changes in human behaviour and, most importantly, by changes in desired family size.”

Income. Education. Contraception. Legal equality. Institutional attitudes.

All are associated with falling fertility rates.

But correlation does not mean it is a cause.

“The problem is there are always exceptions there,” he explains.

“And one of the exceptions …, is what we’re seeing today in Myanmar.”

It’s one of the most impoverished nations in the world.

“Myanmar has below replacement fertility as well. So you don’t have to be an affluent society to have parents choosing very small families.”

Educating women also doesn’t appear to be a cause.

“We’ve got fascinating exceptions also to the overall patterns of modernity, such as the increase in fertility for Israeli Jewry – well above replacement in an affluent, highly educated society in the Middle East. And I think that that further reinforces the importance of volition.”

Families don’t want many children.

“Now the question of what considerations go into this choice is an inescapably human one, and thus a tremendously nuanced personal one,” Eberstadt warns.

“The reasons for choosing less than two children, I would guess, would be rather different in rural Myanmar from affluent Seoul and South Korea.”

And new, coercive birth-enhancing policies being enforced in Russia and China appear to be backfiring.

“I kind of find it reassuring to find out that we’re not rabbits, and we’re not robots, and that we can’t be cheer-led into having different numbers of children from what we’d want,” he comments.

“We can’t be bribed into having a different level of child-bearing than we’d want.”

Riding the population wave

“(It) seems to me there is a lot that human beings and their governments and civil institutions of all various sorts can do to adjust to shrinking and ageing populations – just the way we adjusted to a growing world when we had a population explosion. And that emphasis should be on making the most for humans to flourish,” Eberstadt observes.

The future is one we haven’t experienced.

Growth is the foundation of the modern global economy.

But contraction is now inevitable.

“We don’t know how to cope with this yet, but human beings are very good at coping,” Eberstadt concludes.

This is evidenced by how humanity’s collective efforts managed to dramatically improve living conditions even as populations exploded.

The next century is going to be different.

“It’s not as if we are in a tightly, relentlessly worsening straight jacket,” he adds.

“We’ve got an awful lot of opportunity to help us deal with these inevitable social changes that we’ll be confronting.”

It will need changes in policy.

It will need changes to economics.

It will need changes for communities.

And we can plan for this change.

“And we know enough about how population trends are going to unfold over the next couple of decades because all of the workers for 2040 have already been born,” he explains.

“We know enough that we should already be preparing for a set of social guarantees that transcend the old fashioned ‘Pay As You Go’ model,” Eberstadt adds.

“It’s not going to be all sugar and spice.

“Some particular birth cohort is going to be the one that loses out on the musical chairs. “They’ll have to both start financing their own retirement. And they’ll have ended up paying for somebody else’s.

“I think humane and intelligent government policy ought to be working on something to help compensate that particular group.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social