‘Chain reaction’: Researchers fear Antarctica volcanoes could blow

Millions of tonnes of ice have been keeping the lid on Antarctica’s volcanoes for millennia. Now it’s melting fast, and eruptions are on the cards.

Millions of tonnes of ice have been keeping the lid on Antarctica’s volcanoes for millennia. Now it’s melting. Fast. And researchers say a bout of eruptions is on the cards.

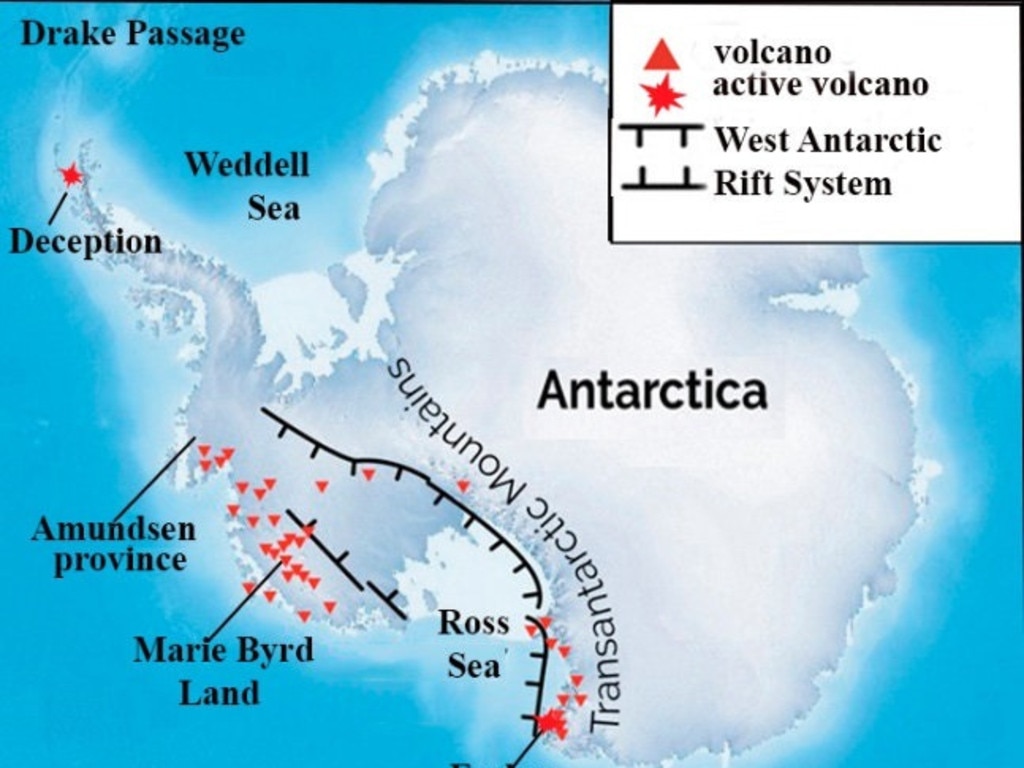

About 100 dormant volcanoes are known to inhabit the southernmost continent.

Some have peaks that extend above the ice sheet. But most are completely buried.

That ice is melting.

The risk of all that water rolling off Antarctica’s land mass and into the oceans has long been known to pose a threat through rising sea levels.

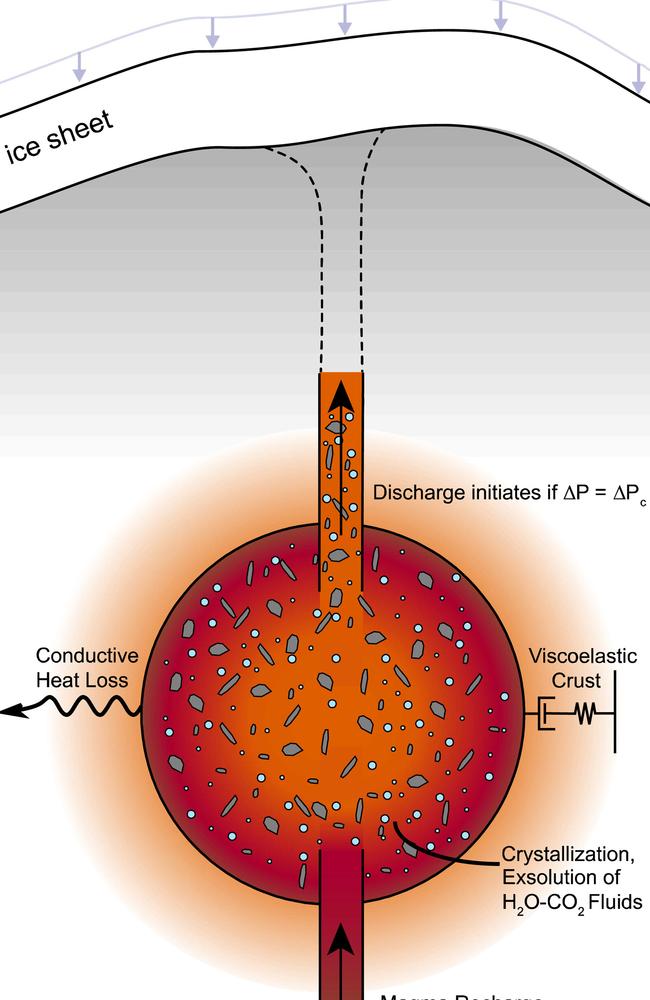

But it’s also removing weight. And that weight has been pressing down on millions of years’ worth of magma build-up beneath Antarctica’s crust.

Researchers are now trying to understand what that means.

And unlike the spectacular lava lakes of Antarctica’s most famous volcano, Mount Erebus, indications are the result won’t be pretty.

Geologist Allie Coonin and several colleagues have published a study in the science journal Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems detailing the results of 4000 computer-model simulations of the changing weight distributions.

The results show the retreating ice will not have to completely disappear before subglacial volcanoes reach trigger point.

“The crustal unloading associated with melting an ice sheet affects the internal dynamics of the underlying magma plumbing system,” the researchers write.

The Brown University Rhode Island researchers noted that the end of previous ice ages was associated with increased volcanic activity worldwide.

And Antarctica’s ice sheets are already beginning to collapse into the sea at an accelerating rate.

“At present, accurate sea-level predictions hinge on our ability to forecast the stability of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet,” the study states.

“The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is particularly vulnerable to collapse, yet its position atop an active volcanic rift is seldom considered.”

Put simply, retreating ice allows the compressed magma below to expand.

That expansion is weakening volcanic chamber walls.

And each volcano has a different point at which those walls will fail as the restraining ice retreats.

The results, simulations suggest, could sometimes be explosive.

Some volcanoes contain vast quantities of dissolved water and carbon dioxide dissolved into the magma. If the magma begins to cool as it expands, these will bubble out of solution.

Superheated steam and gas take up more space.

Like a shaken can of carbonated soft drink, these gases may then vent through fissures in the volcano’s chambers and into the ice cap above.

Such an eruption may not be spectacular.

But the researchers say the effects on Antarctica’s glacial sheets may be catastrophic.

“We find that the removal of an ice sheet above a volcano results in more abundant and larger eruptions, which may potentially hasten the melting of overlying ice through complex feedback mechanisms,” the study concludes.

Melting the subsurface ice will both weaken the glacier and lubricate its contact point with the ground. This rapid melt could cause the glacier to slip towards the sea and further reduce the pressure on the volcano beneath – leading to increasingly large eruptions.

It’s a deadly feedback loop of accelerating eruptions and ice melt.

The authors say this process, while rapid in geological terms, will still take several centuries to unfold.

But, once the feedback loop is triggered, even a successful attempt to curtail the emissions of climate-changing pollutants won’t stop the melt-eruption-melt chain reaction.

And Antarctica’s changing sea ice profile is already affecting global weather patterns.

Warmer oceans have caused ice coverage in the Bellingshausen Sea and Weddell and Ross seas to fall by up to 80 per cent over 1990 levels.

More Coverage

Ironically, the newly exposed sea water cools more than ever before. This causes it to become denser than the warmer water beneath – so it sinks.

According to a study in the science journal Nature, this emerging water movement pattern is beginning to disrupt longstanding deep-ocean currents. And these circulate through the Southern Ocean to produce Australia and New Zealand’s climate conditions.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social