Bulgaria’s Valley of Thracian Kings keeps its secrets

BLINK and you could miss them, as many have before. But in the fields of Bulgaria, these mysterious mounds are everywhere and they hold an ancient secret.

IN THE fields of Bulgaria they are everywhere — hundreds of mounds like huge molehills concealing the gold-filled tombs of ancient kings who left no other trace of their rule.

Known as tumuli, the burial mounds are the only remnants of the Thracian civilisation that inhabited the Balkan Peninsula from the 2nd millennium BC to the 3rd century AD.

The accidental discovery of a tomb in 1944 revealed that the earthen structures were in fact man-made and that the burial monuments hidden within contained intricately crafted treasures.

Experts believe there are more than 15,000 of these tombs in Bulgaria, a tenth of them in the so-called Valley of the Thracian Kings near the central town of Kazanlak.

Many of the tombs have been looted, but a collection of surviving gold, silver and bronze objects are being shown at the Louvre museum in Paris until July 20.

Of the 1500 tumuli in the valley, “only 300 of them have been excavated so far and about 35 revealed such rich burial monuments,” said Kazanlak archeologist Meglena Parvin.

EU funds have been used to restore a handful of tombs that have been opened to public view, but most remain shut because of a lack of money for repairs.

“I feel sad that they are left like that. I hope that more money will come and we can restore and open them,” Parvin said.

Earth goddess

The Thracians were a people of horse and cattle breeders, metal miners and goldsmiths who are believed to have had no alphabet of their own and left no written records.

They believed in the afterlife and the immortality of the soul, and buried deceased rulers with their horses, dogs, weapons, drinking cups and even playing dice.

The kings were considered sons of the great goddess Mother Earth and the burial rites were highly symbolic, Parvin explained.

“When he finishes his journey in this world, the king must return to the womb of his mother. That is the reason why we think that they built these artificial mounds around their funeral structures,” she said.

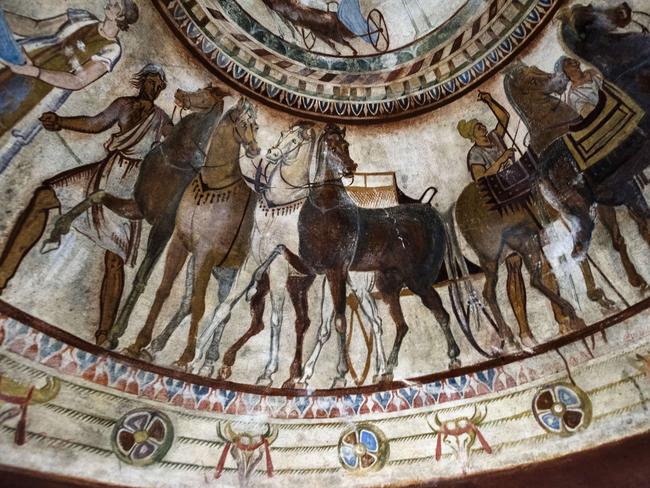

In addition to the treasures, the bushy tumuli also conceal a variety of exquisite burial monuments.

Built from huge granite blocks or bricks, they consist of a corridor and one or more chambers, with each revealing its own meticulous design and ornamentation.

“No two tombs are alike,” Parvin noted, leading the way through the antechamber of the tomb in the Shushmanets mound.

Inside, a slim column helps support the vaulted ceiling of the burial chamber, the walls of which are adorned by seven half columns.

The Ostrusha tumulus nearby contained a sarcophagus-like chamber hewn from a single granite block thought to have weighed 60 tonnes.

Its ceiling contains traces of drawings of people, animals, plants and geometric figures. The remains of six other rooms surround the burial chamber, none of which have been restored as yet.

Emergency repairs

The most famous tomb in the valley is the Kazanlak tomb, which was the first to be unearthed during World War II and has been on UNESCO’s World Heritage List since 1979.

The original is closed to visits to protect its fragile murals, which depict a funeral procession and a horse race, but visitors can view a replica right next door.

The site draws large crowds but the tourism revenue has not been converted into conservation funds, said Sofia-based archaeological expert Diana Dimitrova.

“It is a pity that in Bulgaria somewhere the link is cut and the money from tourism does not go to restorations and archaeological excavations,” said Dimitrova, whose late husband, archeologist Georgy Kitov, excavated most of the tombs in the Kazanlak valley and christened it the Valley of the Thracian Kings.

Dimitrova pointed to the three-chamber tomb of King Seuthes III which provided the pieces for the Louvre exhibition as an example of the problem.

A hit among foreign tourists in the years after it opened to the public in 2005, the tomb has been temporarily closed this summer while awaiting funds for emergency repairs.

“The Thracians built these splendid monumental structures to last forever,” Dimitrova said.

“We cannot just uncover them and leave them like that.”