Ancient city of Petra suffering sharp decline in tourism

HOTELS stand virtually empty and visitors are few and far between. What’s happened to this ancient city that was once bustling with tourists?

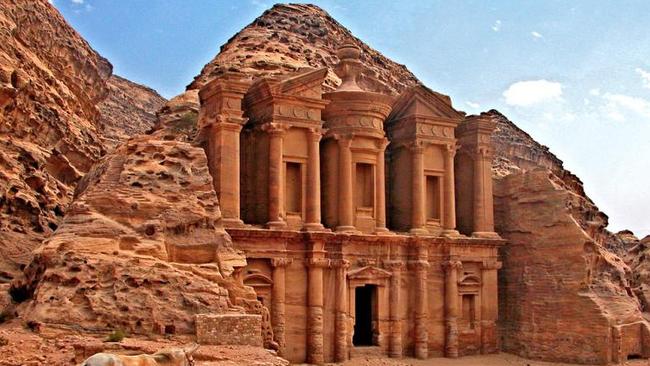

IT’S high season in Petra, an ancient city hewed from rose-coloured rock and Jordan’s biggest tourist draw. Yet nearby hotels stand virtually empty these days and only a trickle of tourists make their way through a landmark canyon to the Treasury building where scenes of one of the “Indiana Jones” movies were filmed.

Petra’s slump is part of a sharp decline in tourism as Jordan’s economy pays a price for regional turbulence and its high-profile role in the U.S.-led battle against Islamic State militants next door. Jordan’s involvement in the anti-Islamic State coalition drew worldwide attention earlier this year, when it stepped up air strikes against targets in Syria after the militants burned to death a Jordanian fighter pilot in a cage. With the harrowing images, war seemed to come closer and tourism suffered, even as the kingdom tried to maintain its traditional image as an oasis of calm in a violent region. Video of the pilot’s immolation, released by the militants in February, led to a surge in cancellations of hotel bookings in Jordan, tourism officials said. The tourism industry, backed by the government, is now trying to lure visitors with price cuts, including waiving some airport fees. But a quick recovery appears doubtful as neighbouring Syria and Iraq sink deeper into violence and Islamic State militants continue to control large areas of both countries. “We are not optimistic for 2015,” said Ahmad Amarat, manager of the 95-room Kings’ Way Hotel near Petra, which closed four months ago after an average occupancy rate of 28 per cent for 2014, compared to 95 per cent in 2010. The tourism troubles are just one of a series of challenges Jordan’s economy has faced since the outbreak of the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011, even though the kingdom experienced little unrest. “The instability in the region affected the economic indicators, mainly tourism, as well as foreign direct investment,” said government spokesman Mohammed al-Momani. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of refugees from Syria���s civil war, now in its fifth year, have strained public services. Still, Jordan’s economy is doing slightly better than the regional average, with 3.4 per cent growth projected for 2015, compared to 1.2 per cent growth achieved across the Middle East and North Africa in 2014, the World Bank said. Before the Arab Spring, Jordan’s tourism industry was going strong, with 8.2 million visitors in 2010. By 2013, that number had dropped to 5.4 million, according to the World Bank. The decline accelerated this year, with the number of overnight visitors down by 50 per cent in the first two months of 2015, said Abdel Al Razzaq Arabiyat, managing director of the Jordan Tourism Board. The slump threatens thousands of tourism jobs, a loss Jordan can ill afford. The official unemployment rate is close to 12 per cent, though actual joblessness is believed to much higher, especially among young Jordanians, creating potentially fertile ground for extremism. In Petra, a UNESCO World Heritage site, the number of annual visitors dropped from 800,000 in 2010 to 400,000 last year, said Yassar al-Majali, general manager of the Jordan Hotel Association. About half of the visitors currently come for day trips, rather than staying overnight, he said. In Wadi Mousa, a town of 25,000 closest to Petra, 10 of 38 hotels were forced to close, including nine in the past year, while others have scaled back staff, said Khaled Nawafleh, head of the Petra Hotel Association. The town has lost 1,500 tourism jobs, he said. Hussam Hamadeen, a 37-year-old father of three, lost his job as a reception clerk after the Kings’ Way Hotel closed. He unsuccessfully looked for work in two other tourist areas — the capital, Amman, 250 kilometres to the north, and in the Red Sea port of Aqaba, 130 kilometres to the south. Now he’s at home, using up his savings. “Everyone here is doing the same, and we don’t know what will happen in a few months when we run out of money,” he said. Nawafleh said he is keeping his Amra Palace Hotel open for now, even though just 20 per cent of the rooms are occupied, compared to 60 per cent last March. The Petra Visitors��� Center, with souvenir shops arranged around a square, is typically jammed at this time of the year. On a recent day this week, only a few dozen people walked around the plaza, where the “Indiana Jones Gift Shop” references a more recent chapter in Petra’s history — the filming of scenes of “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade” in the late 1980s. Some of the individual travellers, including two Americans teaching at an international school in Saudi Arabia, said living in the region helped put security concerns into proportion. “Sometimes it seems things are getting more hyped up. I am not scared to be in Jordan, and I am not scared to be in Saudi, either,” said one of the teachers, 35-year-old Tracy Redding of Chicago. Noor Muqadam, 47, originally from Mumbai, India, but based in Dubai, said he had booked a Petra trip in January, before the video of the immolation of the Jordanian pilot was posted online. After the video he got worried but Jordanian colleagues at work assured him the country is safe, he said. Jordan’s government has been trying harder to bring back tourists. Fees and travel taxes at the airport in Aqaba have been waived to lure back charter flights and discount airlines, said al-Majali of the hotel association. In recent years, Israeli tour operators offering lower prices had won some of the Jordan business, with tourists flying to Eilat, the Israeli port next to Aqaba, and taking day trips to Petra, he said. The national carrier, Royal Jordanian, this week promised discounts on some fares, targeting potential visitors from Europe and the Gulf Arab states. The tourism board, meanwhile, took dozens of travel writers and bloggers on a junket this week, with Jordan’s Queen Rania welcoming the group. But Amarat, the manager of the shuttered Kings’ Way Hotel, said a quick turnaround is unlikely. “Let’s say what is going on in Syria stopped today and they get rid of Islamic State today,” he said, standing in the deserted hotel lobby filled with stacked dining room chairs. “People will not start coming back the next month.” Associated Press writer Mohammed Daraghmeh in Ramallah, West Bank, contributed to this report.