Head chef reveals unbelievable behind-the-scenes detail at Michelin star Dubai restaurant

The head chef of a luxurious restaurant in Dubai, loved by the rich and famous, has revealed the extreme rules they follow to achieve perfection.

Wait staff setting the table with gloves and rulers, and chefs weighing salt to the gram.

Consistency takes on a whole new meaning at Dinner by Heston Blumenthal in Dubai’s luxurious Atlantis The Royal resort.

The restaurant astonishingly received a Michelin star within just a few months of being open last year, an achievement so great, head chef Tom Allen recalls someone influential asking him if he deserved it the very night of the awards.

“What people wouldn’t see from the three months is that we were on the ground in Dubai a year and a half before we went live, tirelessly working 13 to 14 hour days when we had no restaurant,” he says as we chat at a round table in the corner of the restaurant before it opens. The windows reveal a view of Dubai’s iconic Palm Jumeirah and it is pleasantly cool compared to the most intense summer heat I’ve ever felt outside.

To get into the restaurant, guests travel up from the hotel lobby in a round glass elevator surrounded by running water, like being inside a waterfall, and then enter a dark room before stepping foot into the restaurant. There is a giant mechanical pineapple in the centre that opens and closes during the dinner service.

I’m told the distinct scent I noticed when walking in is the signature scent of Dinner, which they are considering turning into candles.

Mr Allen explains that the beauty of the Michelin Guide is that no one really understands how it works. They have “no idea” who the inspectors are or when they visit.

However, he says, maintaining a high standard is not for recognition, but to have a restaurant full of happy diners. In the off season they serve about 500 guests a week, and during busy periods it’s is more like 850 to 950 guests a week.

The aspiration is to have two Michelin stars like Dinner by Heston Blumenthal in London.

This year, they retained their one Michelin star.

As we are talking, Mr Allen points to a well-dressed man with gloves, who is bent over a nearby table concentrating on a ruler.

He explains the staff are setting the tables, measured precisely to the centimetre.

“No way,” I can’t help but say aloud. I thought such an act was reserved for the royal family.

That key word “consistency” comes up again.

“There’s so much we do behind the scenes that they [guests] don’t need to know about,” Mr Allen says.

What it takes to make Michelin star food

In the kitchen, about 12 to 15 sub recipes are used to make one starter, main courses have about 15 to 22, and desserts about eight to 12.

“All of our dishes are very labour intensive,” Mr Allen says.

There is no guess work. If they are making a broth, the same amount of bones will be used each time – even the exact same amount of aromatics, peppercorns, thyme and bay leaves.

The precise weights and measurements mean that regardless who is making the recipe, it will be almost “where it needs to be” each time.

Those recipes will then be adjusted slightly to control different variables – like the cream having more fat at a certain time of year – to get each dish perfect.

Mr Allen describes it as a “very systemised, very controlled, very calculated; a very precise way of cooking”.

He batch tastes everything at 4pm every day. If he is not happy with something, it gives time to troubleshoot. On rare occasions it is not possible to achieve the high standard they desire in time, and therefore they won’t serve the dish at all.

The night before my visit, the iconic triple cooked chips were taken off the menu because they were not perfect, and truffle new potatoes were served instead.

“When you go from the previous years season to the new season, the sugar levels in the potatoes are bit volatile and take a little bit of time to turn from sugar to starch,” he explained of the mishap.

The level of effort put into the food is really driven home later on when I compliment a delicious sauce and I’m told by our waiter (referred to as a Jester) that it took 10 days to make.

Designing a menu based on history

All the dishes at Dinner take are based on British food history and therefore have a backstory.

Mr Allen and Mr Blumenthal work with museum curators and historians to design the menu,

which evolves through the year with seasonality. They aim to change three to four dishes a month.

One new dish can take up to six months to create, involving research, writing the historical story and teaching staff the correct level of table talk, as well as tasting the dish with a sommelier to match wine.

“We go to the British library a couple of times a year, very exclusive access, and we’ll dive into their archives and we’ll take cookbooks from as early as the 13th century, which we have to get translated,” Mr Allen says.

“They are priceless. You have to put gloves on and have little led weights, which are covered in velvet.”

That inspiration is then taken back to the development kitchen in Bray, Berkshire, England and the dishes are “re-imagined”.

At this point, you may assume Mr Allen is a serious, uptight character, but he comes across quite the opposite, laughing and cracking jokes throughout the interview.

He is in his 17th year working with Heston Blumenthal and moved from England to Dubai with his wife and two daughters, 11 and 8, three years ago.

He chooses to live with his family in the Atlantis staff accommodation. The day we meet is ‘Wellness Wednesday’, where Dinner staff play sports like badminton and football in the sports hall before work.

The highest standard of service

It becomes extremely clear working at Dinner by Heston Blumenthal is no typical hospitality gig as my colleague and I return for a meal in the evening.

Pierrick, our waiter, who is more like a professor feeding our curiosity, tells me he underwent 14 weeks of intense training, including British history, before the restaurant opened.

At the end of each week, they had an exam, and still to do this day they have an all-staff briefing every day before guests arrive with a surprise pop quiz.

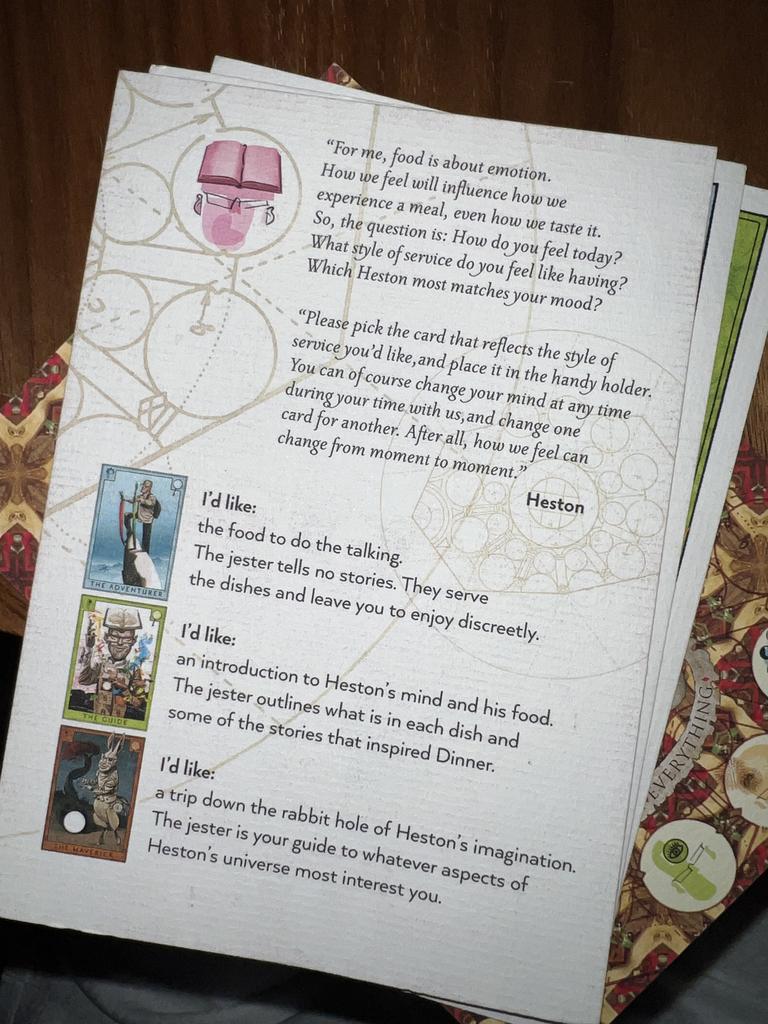

Notably, while the staff are well-educated, Dinner acknowledges not every diner wants the full history behind what they are eating.

Guests choose the level of interaction they have with their wait staff via a card system.

“When I personally go to a restaurant, I don’t want much interaction,” Mr Allen says.

On every table there are three cards to choose from: the ‘adventurer’ who wants the food to do the talking, the ‘guide’ who wants to know what is in each dish and the historical reference, and the ‘maverick’ who likely has been wanting to visit for a long time and wants to know the whole developmental process.

“We were concerned people might find it a bit edgy but it takes away that awkwardness, some people maybe don’t want to say ‘look I’m here for a business meeting leave me alone’ or ‘I’m on a date’. It just helps get what you want out of an evening,” Mr Allen says.

Atlantis The Royal is a celebrity haven (Beyonce reportedly got paid $A35 million to perform at the hotel’s grand opening last year).

Mr Allen says they have had a number of A-listers dine from sports people to musicians and actors, but he doesn’t go as far as divulging their names.

“We have rules; we don’t ask for autographs and we don’t ask for photographs. If they want to come up to kitchen and have a photo we’ll obviously embrace that,” he reveals.

If another diner recognises a celebrity guest and attempts to approach them, wait staff are expected to defer them.

Dining at Dinner in Dubai

The restaurant’s signature dish is the meat fruit (c. 1500).

It is inspired by a dish Henry VIII, the famous former king of England, served guests at a dinner party.

“Back then people thought eating raw fruit and vegetables, that there were toxins in them and it wasn’t good for you, so they felt you had to cook the fruit and vegetables before you could eat it,” Mr Allen explains with bright eyes, still excited to tell the story for what is probably the millionth time.

The original dish, he says, would have been veal mince dipped in parsley custard, made to look like an apple.

“Everyone was kind of like ‘I don’t want to touch this’ because I’m going to get sick’. And he would grab the apple and cut into it, and eat it because he knew what it was.

“It was a bit of trickery, things aren’t as they seem, and that ties in nicely with what Heston does.”

The meat fruit on the Dinner menu is a chicken liver parfait disguised as a mandarin.

But as we spoke, Mr Allen revealed they were in the final stages of developing an alcohol-free date meat fruit in honour of Dubai.

They also make an alcohol-free ‘tipsy cake’ at the Dubai restaurant, which is a brioche pudding with pineapples that Mr Allen describes as “one of my favourite things to eat even after 13 years”.

The pineapples are spit roasted for four to five hours and coated with apple caramel every 30 minutes.

That giant mechanical pineapple I mentioned earlier, is connected to the spit.

The main religion of Dubai is Islam, which prohibits consuming alcohol. While restaurants in the city can still cook with and serve alcohol, it gives Muslim guests an opportunity to experience the iconic dishes.

All meat must also be halal at Dinner by Heston Blumenthal in Dubai, unlike the London location.

Knowing I’m from Australia, Mr Allen shares they source their truffles and Wagyu beef from Australia, and venison from New Zealand.

To get the most out of Dinner, a diner must really embrace the fact it is not just a meal, but an experience.

I was admittedly nervous to try some of the options on the menu, but was blown away by the most strangest sounding dishes. The food certainly doesn’t just look good. Some of the tiniest details on the plate packed the most impressive flavours.

I still struggle to believe I ate a green savoury porridge with snails (c. 1661) and found it delicious.

If guests want to end the experience with a bang, my recommendation is to order ice cream.

It is made by your table on the liquid nitrogen ice cream trolley (c. 1901) – a show and dessert in one.

This writer was a guest of Atlantis.