Wet and mild in sea lion swim

SWIM with sea lions at South Australia's Baird Bay and you'll soon become a devoted fan, writes Peter Needham.

THEIR eyes are dark and soulful and their faces silvery brown. Their muzzles are adorned with long, elegant whiskers. These are Australian sea lions, rare and beautiful, and we are off to swim with them.

Our little group has set out from Baird Bay on the western coast of South Australia's Eyre Peninsula aboard Investigator, a 12m launch skippered by Alan Payne.

During our short voyage to the sea lion colony on Jones Island, dive assistant Troy McCurdy gives a few words of advice: "When you swim, try not to kick. The pups like to smell your feet. Hold their focus by staring at them. They are a lot like dogs."

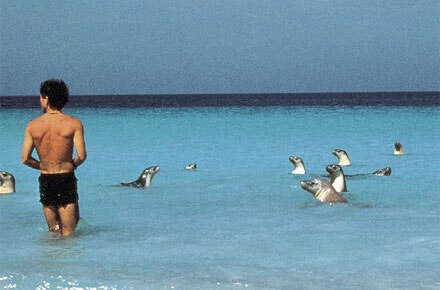

Approaching the island, Payne stops the launch and we transfer, in our wetsuits, to a small flat-bottomed aluminium boat. The sea lions, perhaps 25 of them, are straight ahead, basking on the foreshore of the long, low island. Our destination, about 200m offshore, is a clear, shallow lagoon, about 2m deep, where the sea lions enjoy swimming with Payne and his guests.

Payne has befriended these handsome animals over the years, without offering them food or any other reward or inducement. "You don't need to feed an animal to be friends with it," he says.

Members of our party don snorkels and masks and slip into the crystalline water as a couple of inquisitive sea lion pups swim out to meet us, popping up a few moments later next to the boat.

Sea lions prove easy to meet. As I dip beneath the water, a creature with an intelligent, puppy-like face swims up, looks me in the eye and does a sort of underwater somersault. Moments later, it swims up again to give me a playful, doggish nudge. Its whiskers are bristly and its fur feels like a wetsuit.

This sea lion pup, which Payne calls Fang, is eight months old, still feeding on milk and highly playful. Fang is followed by another couple of pups, then more, until about 10 of various sizes are diving and cavorting acrobatically, with human snorkellers bobbing between them.

Back aboard the launch, delight is universal. "I could say that was my best-ever swim, but I say that once a week," McCurdy laughs.

The Investigator zooms off in search of dolphins, making a wide arc at high speed. The dolphins are located in much deeper water, a tad too challenging for my limited swimming ability. I watch from the vessel's bridge. It's all over pretty quickly. The group of snorkellers forms a semicircle, a couple of dolphins pop up and dive again.

That evening we stay at the Baird Bay Ocean Eco Apartments. Built of sandy-coloured rammed earth, they are comfortable, light, airy and well-furnished, and constructed on sound ecological principles. The establishment is run by Payne and his wife, Trish, and sea lions dominate the conversation.

Apparently this focus is not unusual. Payne says people arrive thinking dolphins will provide the most memorable experience, only to have sea lions win them over. Some swimmers compare dolphins with aquatic cats and sea lions with dogs.

Isolated Baird Bay is an ideal place to get away from it all. This tiny hamlet of a few houses (or shacks, in South Australian parlance) lets travellers share a long stretch of crunchy, honey-coloured sand with abundant pelicans, numerous birds of other species, passing wallabies and the occasional dingo. Payne arrived on a motorbike 16 years ago, liked the place, bought a cheap plot of land and stayed. He and Trish bring Baird Bay's resident population to eight.

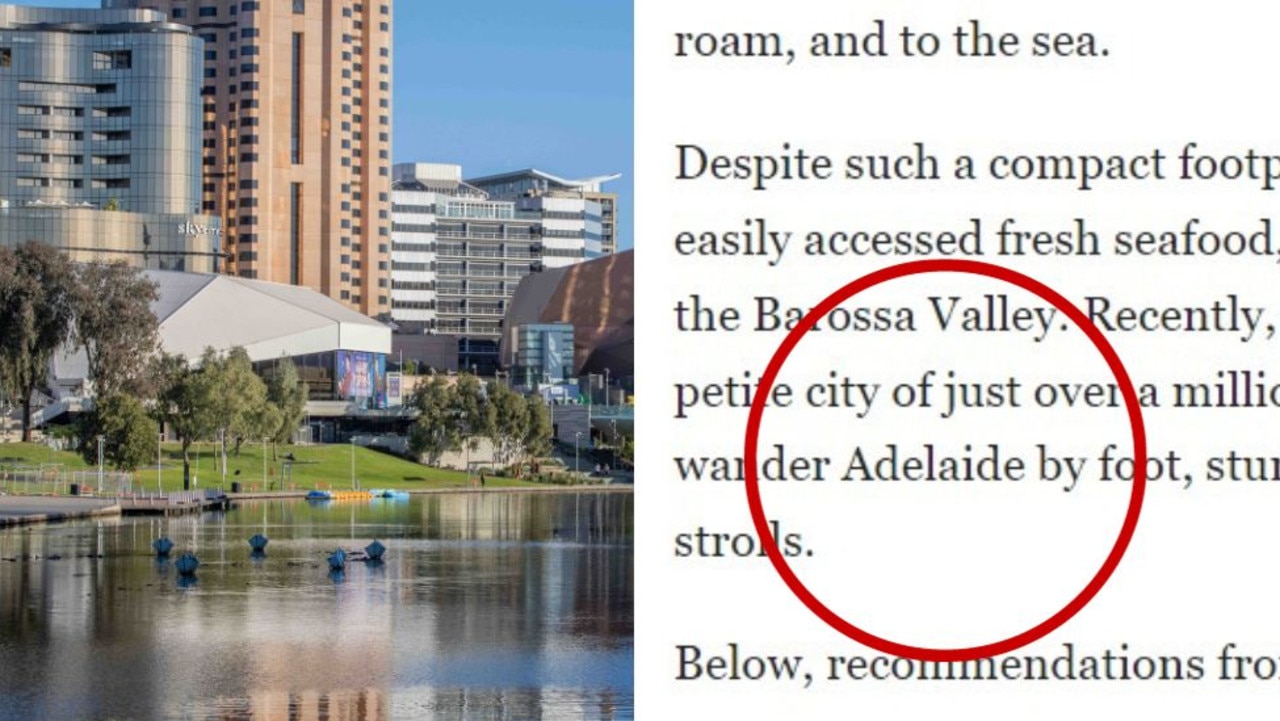

Seafood, aquaculture, marine mammals and fish are the lifeblood of the Eyre Peninsula, the triangular wedge jutting towards the Southern Ocean on the eastern side of the Great Australian Bight. Scenery includes crumbling drystone walls built by early settlers, steel windmills, massive cliffs towering over relentlessly pounding waves and salt lakes of the palest aquamarine.

As well as sea lions and dolphins, you can swim with cuttlefish and tuna and even great white sharks (a sturdy cage protects you for this particular adventure). The biggest fishing fleet in the southern hemisphere sails from Port Lincoln on the western side of the peninsula. Southern bluefin tuna, abalone, mussels, oysters, prawns, crayfish, scallops and Murray cod are all farmed or caught around here. So bountiful is the catch, local restaurants often ensure they have beef or rack of lamb on the menu in case regular patrons tire of eating some of the world's finest seafood. Few visitors face that problem.

On the peninsula's western shore, drive or sail from Anxious Bay to Coffin Bay, passing Mt Hope on the way. Coffin Bay, named after a 19th-century naval officer, is an oyster lover's nirvana. Diners at the Oysterbeds cafe and restaurant savour choice local specimens while watching pelicans flap lazily overhead. Try oysters here, au naturel, creamy and delicious, or with lime, coriander and ginger, perhaps soy, mirin and wasabi or horseradish butter and parmesan.

Local Living Tree olive oil and fresh-baked bread make a fine accompaniment as does Coopers Stout (South Australia's finest) or crisp Lincoln Estate Sashimi Sauvignon Blanc 2007.

Port Lincoln, near the peninsula's tip, a short hop by air from Adelaide, is Australia's aquaculture and seafood capital. It's also an important wheat exporting port, with huge silos facing the foreshore. Its tourist season peaks during the Australia Day weekend, when the Tunarama Festival doubles the population (usually about 14,500). Tunarama is more than 40 years old. Its most celebrated event is the tuna toss, in which participants compete to hurl large dead fish. The record, set in 1998 by athlete Sean Carlin (who won gold for Australia in the hammer throw at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics), stands at 37.23m.

Port Lincoln enjoys a Mediterranean climate and a clutch of very wealthy residents; by some estimates, the highest proportion of millionaires per capita in Australia live here. The main source of the wealth is fishing, particularly for southern bluefin tuna. Prices in Japan for this species have reached $133,000 for a single fish, though the average is between $5000 and $10,000.

These days, Port Lincoln has a genteel look. A fine new four-star, 111-room resort hotel, the Port Lincoln, opened at the end of last year. The hotel's Sarins Restaurant is named after owner Sam Sarin, one of the town's best-known residents, who built his fortune on, you guessed it, tuna. If dining at Sarins, try the tea-smoked Coffin Bay oysters and black mussels.

Smart cafes line Port Lincoln's main street and a bronze statue of local racehorse Makybe Diva graces the foreshore.

Back in the 1980s, tuna boat crews brawled in the local pub, fired shots at each other on the high seas and spent their earnings in a day or two as wildly as possible.

Graham Daniels of Marina Boat Cruises gives vivid accounts as visitors putter around Lincoln Cove Marina and surrounding waterways in his electrically powered launch Tesia. Cruise past the mansions of fishing millionaires, bedecked with statuary, their huge yachts moored outside.

See the commercial harbour, where Daniels will teach you how to tell a prawn trawler from a tuna boat. He worked on the boats during the tuna "gold rush", when crews threw pilchards into the sea to attract tuna, which were then "poled" by crewmen hanging off the back (without a harness).

The technique involved skewering tuna with a barb-less hook and flipping them through the air on to the deck. If they poled two tuna, the catch was theirs and other boats better steer clear: such was the unwritten law. Poling, always dangerous, has long since disappeared. Today, more than 90 tuna boats in the Great Australian Bight use safer methods to catch their quota of about 5200 tonnes.

In the meantime, tuna farming has come into its own. You can even swim with the fish. Matt Waller, a fourth-generation Port Lincoln fisherman and tuna expert who runs Adventure Bay Charters, can arrange that. Waller's tuna, which seem almost like his pets, dwell contentedly in a special offshore pontoon. Their enclosure replicates a commercial tuna farm; it's enclosed with undersea nets and protected by electric fences and cameras to deter tuna rustlers and desperate anglers.

More than 70 tuna, worth about $700 each at this stage of their development, swim in this pen. Hold a pilchard above the water and a tuna will jump up and catch it, its jaws snapping like a rat trap as it seizes the prize. You can climb in and snorkel with these muscular, fast-moving fish, which zip around like torpedoes at 70km/h, swerving adroitly to avoid you.

Tuna are interesting but, as Waller admits, they are not big on personality. In personality terms, sea lions beat them hollow. But Waller has that covered, as his Adventure Bay Charters now offers sea lion swims as well.

Peter Needham was a guest of the South Australia Tourism Commission.