Long ignored female songbirds do sing: And they’re glad you never noticed

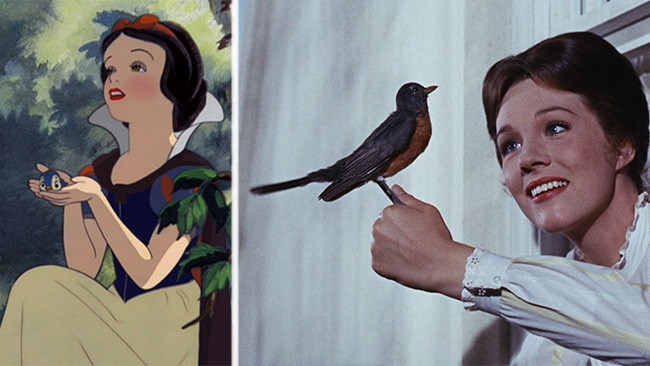

DISNEY got girls wrong — again. Female songbirds do actually sing and compose their own songs. But they’re glad you never noticed!

DISNEY got girls wrong — again. The popular notion that brightly coloured male birds do all the singing while the gals sit demurely on their nests has been turned on its head. But it has ominous implications.

They’re beautiful. They’re intelligent. And the song of the superb fairy wrens (Malurus songbirds) hold a special place in the heart of every Australian who has stepped outdoors.

While the bright plumage and chatter of the blokes prancing about on the fence rails and tree branches win our attention, a study of the wrens’ songs has revealed something new.

They’re not just masculine declarations of territory and lady wooing.

The more demure girls sing, too.

It’s a different — softer — song, often sung for different reasons.

And at great personal risk.

Flinders University Professor in Animal Behaviour Sonia Kleindorfer has paid particular attention to the types of songs the little wrens sing, going so far as to put tiny heart monitors into nests filled with eggs.

The results of her work has been published in the science journal Biology Letters.

“For decades scientists overlooked female song because it was perceived as being infrequent and soft, and was therefore considered that females copied male song”, says Professor Kleindorfer.

“While naturalists focused on colourful males and loud male-male contests, female song was not thought to have any real purpose on its own. It was ignored. But we are finding that they do sing — and they are very clever about it.”

She’s found the doting mothers quietly sing lullabies to their unhatched eggs.

They’re teaching them ancestral tunes. They’re soothing them.

But, in doing so, the mother fairy wrens risk broadcast their position.

“Our study provides the first explanation for why females sing less conspicuously than males: not because their song is less important — but because female song attracts predators to the nest,” says Professor Kleindorfer.

Put simply, her study found the more the girls sang — the more prone they, and their nest, was to predation.

But their nurturing instinct remains strong. So, they’ve learned to tone down their tunes to reduce the risk — while still managing to reassure and inspire their anxious offspring.