Scary map exposes huge China war threat

It’s something most people never even think about – but if China attacked this as its first act of war, the world as we know it would all but stop.

What would happen in minute one of any future war? The internet would go down.

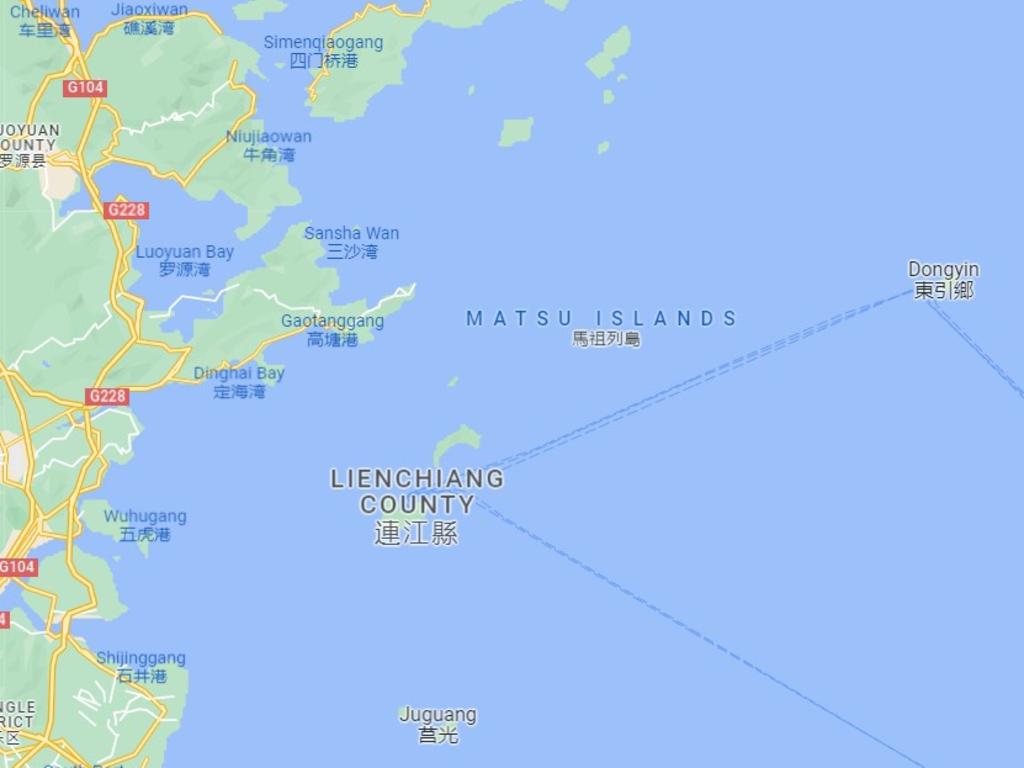

China has highlighted this critical international security vulnerability by cutting submarine internet cables to Taiwan’s Matsu Islands. Now nations across the world are nervously looking at their own exposed connections.

It’s plausible that the 500km-long Matsu Islands cables were cut by accident. Again.

It’s the 27th time it has happened in the past five years. It’s generally attributed to Chinese fishing vessels ignoring the warnings on their charts and dropping anchors on the fragile lines of communication.

This time, the outage has lasted almost a month, prompting many of Matsu Islands’ 14,000 mobile-phone-dependent residents to flee to the Taiwanese mainland.

But there are always suspicions such wayward fishers were actually members of Beijing’s “Fishing Militia” – a fleet of disguised espionage boats crewed by Communist Party members trained to enforce China’s aggressive territorial claims.

Cutting cables is a “way of showing that Beijing can disrupt the information environment, whether that be civilian, commercial or military,” says Stanford University international affairs analyst Oriana Skylar Mastro.

It’s a message that can be sent on a global scale.

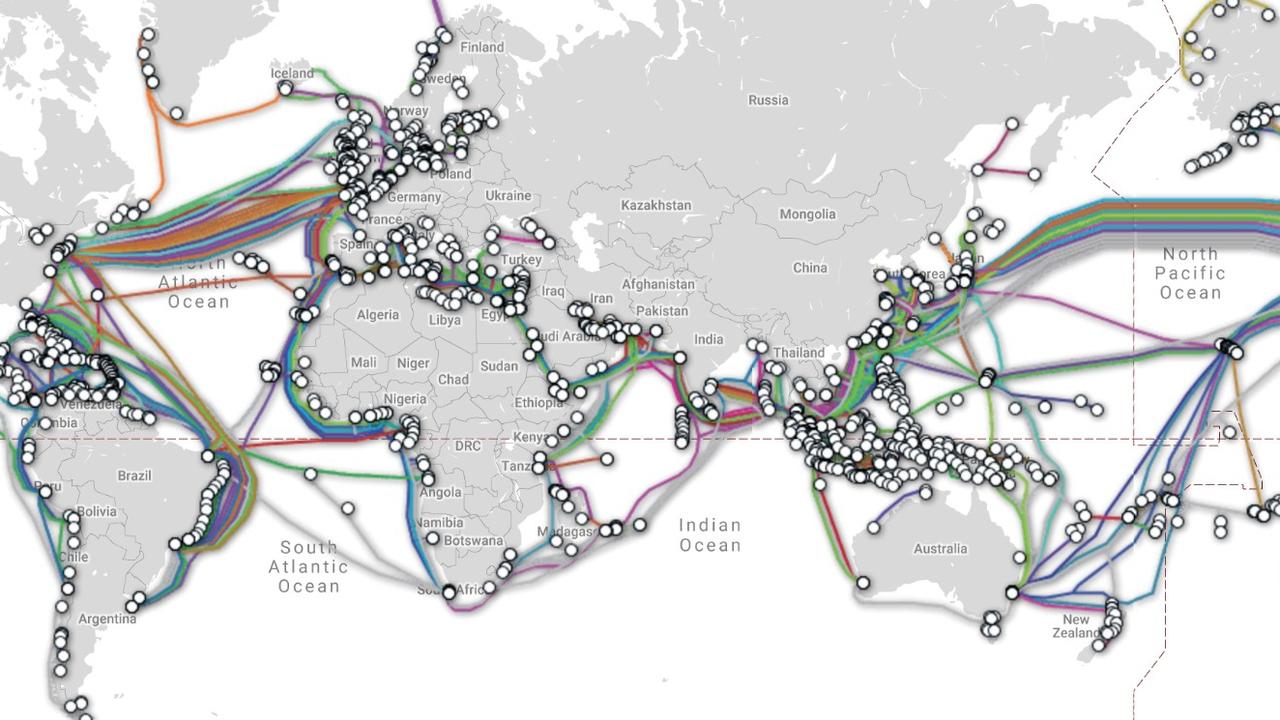

Almost 95 per cent of the world’s international digital traffic is carried by 1.3 million kilometres of undersea cables – all not much thicker than a garden hose and laid out in some 400 separate lines.

These carry everything, including emails, banking transactions, video streams – and military data feeds.

“In the financial sector alone, undersea cables carry some $US10 trillion [$A15 trillion] of financial transfers daily,” Centre for Strategic and International Studies analyst Pierre Morcos says.

In 2008, a cut cable near Egypt caused US combat drone flights over Iraq to fall from hundreds each day to just a few dozen. Last year, a line linking a satellite communications station in the far north of Norway was severed.

Cutting the cord

Communications cables are a valid military target.

“There are several conceivable objectives severing a cable might achieve: Cutting off military or government communications in the early stages of a conflict, eliminating internet access for a targeted population, sabotaging an economic competitor, or causing economic disruption for geopolitical purposes,” Mr Morcos says. “Actors could also pursue several or all of these objectives simultaneously.”

And Australia’s been targeted with such aggression before.

During World War I, the German light cruiserHMS Emden attacked an Australian telegraph relay station on Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean.

Only after the damage was done did the cruiser HMAS Sydney score Australia’s first victory at sea by sinking the raider.

Modern undersea internet cables are not exceptionally resilient. At their heart are bundles of glass fibres, each about as thick as a human hair. Information is passed along these strands in the form of pulsed light. They are covered in sheaths of copper, nylon and plastic. But this serves mainly to protect them from shark bites and temperature extremes.

And like the Cocos Island telegraph station, these cables come ashore to exposed – and well-known – data distribution centres.

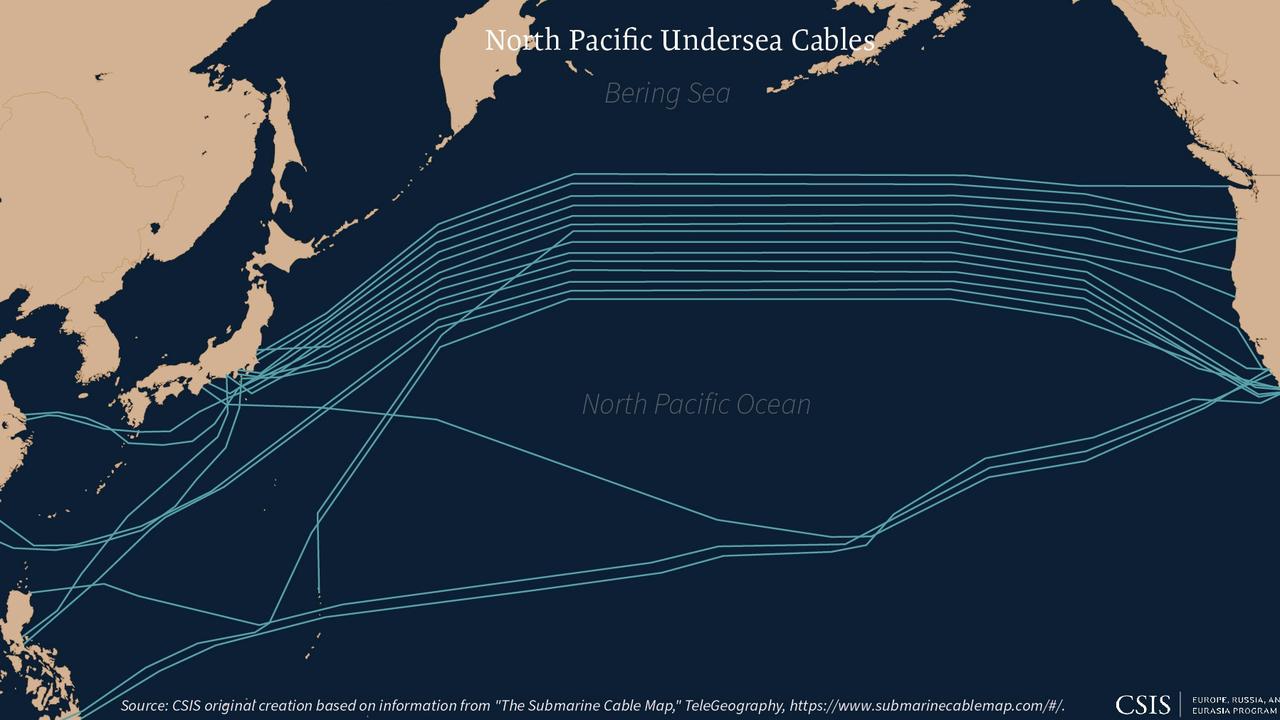

The bombing of the Nord Stream gas pipeline running along the bottom of the Baltic Sea last year highlighted how vulnerable Europe’s critical submarine infrastructure is. For example, most of its cloud-based data servers are based in the US.

Britain, France and Italy are now investing in new ships and underwater drones to protect these lines of communication against saboteurs.

One such suspect is the Russian research ship Akademik Boris Petrov. It was seen leaving the Shetland Islands when the submarine cable linking it to Scotland was severed in October last year. It was also escorted out of Netherlands waters after being observed tracing underwater gas pipes and data lines.

But most cable breaks – between 150 and 200 annually – are caused by fishing vessels, shipping and earthquakes. Specialist repair ships must be sent to each break, locate the ends, lift them to the surface and splice them back together.

Wire-tapping

Cords cuts are not the only risk, analysts warn. They can also be compromised.

Atlantic Council analyst Justin Sherman recently told Reuters that undersea cables were “a surveillance gold mine”.

“When we talk about US-China tech competition, when we talk about espionage and the capture of data, submarine cables are involved in every aspect of those rising geopolitical tensions,” he said.

Mr Morcos says the world’s intelligence agencies are busily “tapping them to record, copy, and steal data, which would be later collected and analysed for espionage”.

This can be achieved by building “back doors” into the network during cable manufacturing, targeting coastal landing stations, or directly tapping the wires at sea.

“A nightmare scenario would involve a hacker gaining control, or administrative rights, of a network management system,” he says. “At that point, they could discover physical vulnerabilities, disrupt or divert data traffic, or even execute a ‘kill click’ deleting the wavelengths used to transmit data.”

But Council on Foreign Relations analyst Joshua Kurlantzick says tapped internet links could also become a deadly information manipulation tool.

“Beijing wants to silence conversations about many topics – Xinjiang, Tibet, the South China Sea, its Covid-19 policies, and so on. It wants to make these tough topics disappear,” he writes.

“If Beijing had more control of the pipes of information, it also could, within foreign countries, more easily censor negative stories and social media conversations, and spread stories, rumours, opinions, accusations, blandishments, and other types of disinformation, obviously types of sharp power.”

It’s a subtle but powerful way to wield international influence.

“China could achieve this outcome, of course, through clear and open threats to punish other countries with economic measures, diplomatic measures, or other sanctions, for instance,” he says, referring to Beijing’s coercion campaigns being waged against the likes of Australia, Canada and Taiwan. “But the bullying approach … has major downsides as well.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel