FBI won’t reveal how a locked iPhone used by the San Bernardino attackers was accessed

IN a move with far-reaching security implications, the FBI says it will not publicly disclose how a locked iPhone used by the San Bernardino attackers was accessed.

THE FBI says it will not publicly disclose the method that allowed it to access a locked iPhone used by one of the San Bernardino attackers, saying it lacks enough “technical information” about the software vulnerability that was exploited.

The decision resolves one of the thorniest questions that had confronted the federal government since it revealed last month that an unidentified third party had come forward with a successful method for opening the phone.

The FBI did not say how it had obtained access, leaving manufacturer Apple Inc. in the dark about how it was done.

The new announcement means details of how the outside entity and the FBI managed to bypass the digital locks on the phone without help from Apple will remain secret, frustrating public efforts to understand the vulnerability that was detected and potentially complicating efforts to fix it.

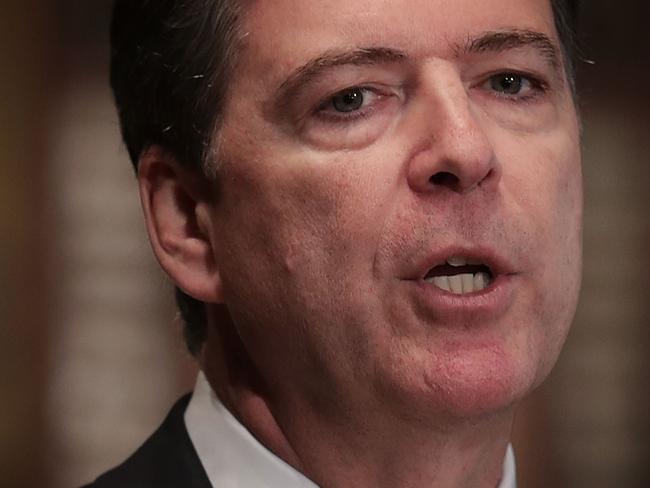

In a statement on Wednesday, FBI official Amy Hess said that although the FBI had purchased the method to access the phone — FBI Director James Comey suggested last week it had paid more than US$1 million (AU$1.3 million) — the agency did not “purchase the rights to technical details about how the method functions, or the nature and extent of any vulnerability upon which the method may rely in order to operate.”

The government has for years recommended that security researchers work cooperatively and confidentially with software manufacturers before revealing that a product might be susceptible to hackers.

The White House has said that while disclosing a vulnerability can weaken an opportunity to gather intelligence, leaving unprotected internet users vulnerable to intrusions is not ideal either.

An interagency federal government effort known as the vulnerabilities exploit process is responsible for reviewing such defects and weighing the pros and cons of disclosing them, taking into account whether the vulnerability can be fixed, whether it poses a significant risk if left unpatched and how much harm it could cause.

Hess, the executive assistant director of the FBI’s science and technology branch, said the FBI did not have enough technical details about the vulnerability to submit it to that process.

“By necessity, that process requires significant technical insight into a vulnerability.” she said.

The revelation last month that the FBI had managed to access the work phone of Syed Farook — who along with his wife killed 14 people in the December attacks in San Bernardino — halted an extraordinary court fight that flared a month earlier when a federal magistrate in California directed Apple to help the FBI hack into the device.

Earlier this month Comey said the FBI had not yet decided whether to disclose details to Apple but suggested the agency had reservations about doing so.

“If we tell Apple, they’re going to fix it and we’re back where we started,” Comey said. “As silly as it may sound, we may end up there. We just haven’t decided yet.”