NFTs explained: What is a non-fungible token and why are Elon Musk, Kings of Leon and Jack Dorsey selling them

Another obscure abbreviation is taking the world by storm as speculators race to cash in, but not everyone is crazy about the new idea.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have been generating a lot of attention and headlines in the tech world in recent weeks, leaving many intrigued by their potential and many more scratching their heads wondering what exactly they are.

They’ve been heralded as the future of art and music and potentially the next best investment since Bitcoin, but they’re not without drawbacks.

So what are NFTs and are they here to stay?

WHAT IS A NON-FUNGIBLE TOKEN (NFT)?

An NFT is similar to cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum, in the sense that they rely on the same “digital ledger” known as blockchain.

Blockchain works by creating an open and distributed record of transactions that’s nearly impossible to alter.

Rather than storing data in tables in a database, the data fills up “blocks” which are then linked to the previous blocks

In the context of Bitcoin, each new “coin” mined contains the history of previous Bitcoin, and they all talk to each other in a sense to ensure the database contains the correct information about who owns what coins and when they’ve been traded.

This provides security because if you’re a hacker who wanted to steal Bitcoin you would have to control enough of it to start with that altering a coin’s data to make you its owner wouldn’t be automatically corrected by the rest of the blockchain — and if you managed to get over that practically insurmountable hurdle, the Bitcoin you were able to steal would be rendered essentially worthless anyway because it would no longer be secure.

Cryptocurrencies and NFTs rely on similar architectures and philosophies, and you need the former to buy the latter, creating a barrier for entry for newcomers, albeit one that doesn’t seem to be slowing down the recent rise of NFTs.

The difference is that Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are “fungible” and interchangeable, you can trade one Bitcoin for one Bitcoin.

As the name suggests, NFTs are not fungible, they are one-off certificates or “tokens” of a particular thing that can theoretically be traded but not recreated — a bit like buying an original painting — and that’s partly led to its embrace in the worlds of art and investment, and their intersection in the real world they exist in.

HOW ARE NFTS BEING USED?

With the crazy pace of the world these days you might not remember who Martin Shkreli is, but if you do it’s highly likely your memory is not a fond one.

Mr Shkreli became something of a modern-day villain in the last decade, upping the prices of medications before being jailed for unrelated securities fraud, and doing it all with a boyish smirk on his face.

RELATED: Aussie invention ‘recipe for disaster’

Prior to his notoriety he also paid $US2 million ($A2.58 million) for a one-of-one album from Staten Island rap group the Wu-Tang Clan, who made the single-copy album with the hope of restoring value to music, complete with stipulations that it couldn’t be resold until 2103.

“The intrinsic value of music has been reduced to zero. Contemporary art is worth millions by virtue of its exclusivity,” Wu-Tang members wrote at the time.

“By adopting a 400-year-old Renaissance-style approach to music, offering it as a commissioned commodity and allowing it to take a similar trajectory from creation to exhibition to sale … we hope to inspire and intensify urgent debates about the future of music.”

RELATED: Elon stuns with monkey brain chip claim

Those urgent debates might not have happened as streaming behemoths like Spotify and rivals like Apple Music continued gobbling up the music industry, who were just happy to receive some form of income after years of internet piracy, even if very little of that money would trickle down to their artists.

But the Wu-Tang Clan’s plan may have foreseen the potential power of NFTs to restore monetary worth to music and art in a world where both can be quickly and easily reproduced using technology.

RELATED: ‘That is creepy’: Cops deploy robot dog

RELATED: Eerie website brings dead back to life

NFTs also have the capability for stipulations like the type Wu-Tang put on its one-off album to be included in the contract that makes you the owner of the token.

Musicians are intrigued, and that’s pushing NFTs to the fore as famous faces jump on board.

According to Music Business Worldwide, more than $US25 million ($A32.2 million) in music sales via NFTs have occurred in the past month.

American band Kings of Leon recently announced their next album will be available as an NFT.

Other artists to release music or merch as an NFT include Shawn Mendes, 2 Chainz, Jack Harlow, and Grimes.

Grimes’ slightly more famous partner Elon Musk recently got in on the action too, releasing a song about NFTs that he planned to sell as an NFT.

RELATED: Unexpected phenomenon to launch in Aus

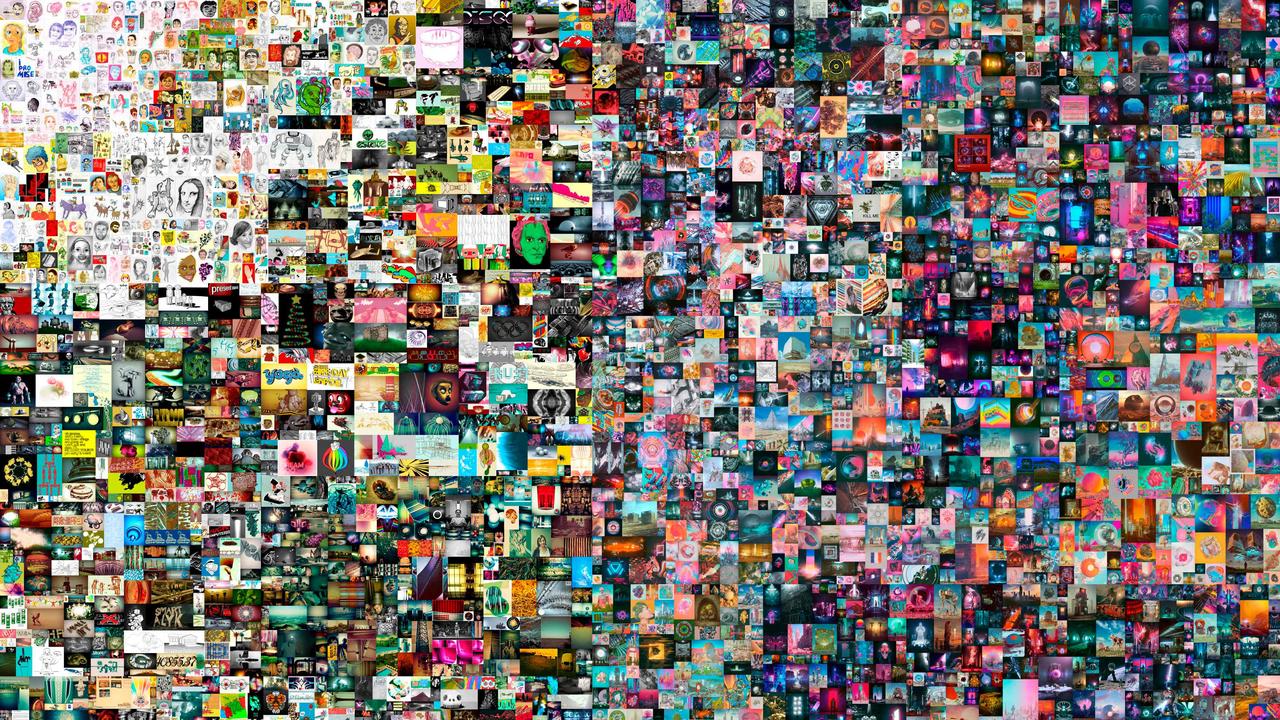

Christie’s, known for its fine art auctions, recently embraced the technology with the sale of an NFT for a digital collage by artist Beeple, which fetched an eye-watering $US69.4 million at auction.

Beeple reacted to Mr Musk’s song about the technology that had just made him very wealthy with a joking offer to buy the NFT of Mr Musk’s song with the proceeds from the Christie’s auction.

i'll give you $69M for it. https://t.co/DMd4EEOGCZ

— beeple (@beeple) March 15, 2021

RELATED: Elon Musk’s ‘flamethrower’ seized in bust

Beeple might even sell that tweet as an NFT, new platforms are seeking to make it possible, providing a way for online “creators” to get paid for their content.

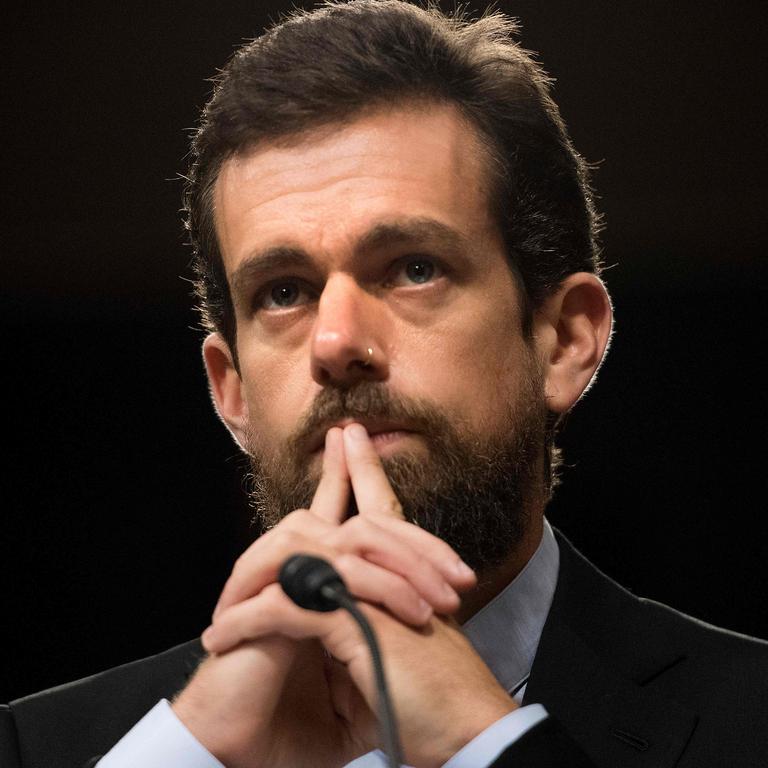

Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey’s first ever tweet is being auctioned off as we speak, attracting a $US2.5 million ($A3.2 million) offer.

He plans to cash that in next week and donate the proceeds to a charity.

As is the attraction with buying fine art or other rare items, it’s assumed that NFTs will increase in value over time, making the purchase an investment as well as an acquisition.

WHAT’S THE DOWNSIDE?

The implications on the future of society and the economy are numerous when it comes to cryptocurrency and NFTs, but to avoid speculating wildly all day on its hypothetical future pitfalls, we’ll focus on the one many have sought to highlight in relation to NFTs and the wider cryptocurrency movement.

The process of creating and maintaining a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin and Ethereum has, by design, extremely intensive demand for electricity, which currently creates an associated emission of greenhouse gases when the power comes from a non-renewable source.

Estimates from Digiconomist, a platform “dedicated to exposing the unintended consequences of digital trends”, claim Bitcoin has an annual energy requirement of around 82.03 TWh, which it says is comparable to the entire power consumption of Chile, a nation of around 19 million.

A single Bitcoin transaction is estimated to use 744kWh of electricity.

RELATED: Fears power bills could rise

RELATED: Elon’s secret plan for power revealed

Figures from this reporter’s most recent energy bill suggest that’s equivalent to the amount of power a five-strong household in Sydney would use in 38 days, but a Bitcoin transaction only takes seconds.

Ethereum, which has been more widely used for NFTs due to its contracts that allow for the Wu-Tang style stipulations, uses an estimated 60.64 kWh per transaction, enough to keep an Australian family cool in their home for three days.

That energy use, and the associated release of greenhouse gas emissions until the computers that provide the backbone of cryptocurrencies are powered by renewable energy, has led to some backlash from artists and audiences who don’t want to contribute to it.

Beeple himself said his future NFTs will be carbon neutral or negative through the purchase of offsets and investments in renewable energy projects.

Other artists have cancelled planned NFT collections after learning about the associated ecological cost.

The future of NFT and cryptocurrency and whether they achieve some of the loftier expectations that have brought a surge in interest could depend on whether they can lower their carbon footprint in a rapidly decarbonising world.