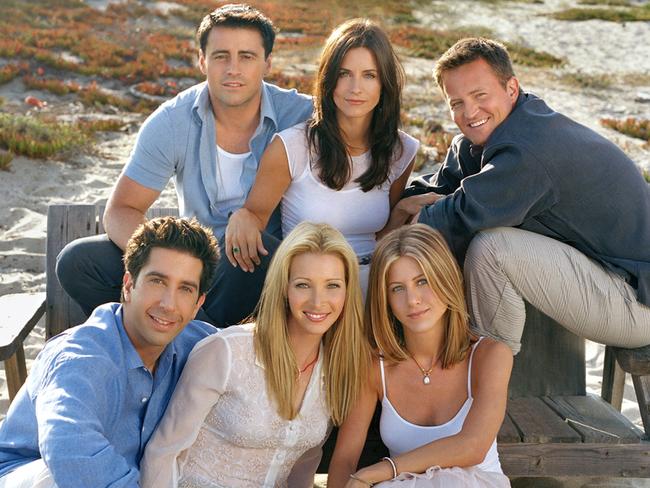

Friends is still insanely popular: Why Gen Y are nostalgic for an era they didn’t experience

THE antics of the entire Friends gang haven’t aged well, but there’s a strange reason the show is still a juggernaut.

THERE is a simple sitcom that’s a massive hit with Gen Y, sweeping high schools and colleges all around the world. Netflix paid $118 million for the US-only rights to stream the show, while screenings on NBC and its subsidiary channels attract a whopping 16 American million viewers each week.

Friends, that warm-hearted staple stuck firmly in the ’90s, is still a massive success in 2018. And the biggest audience for it isn’t those who fondly recall their own flannel-clad youths, but those who are too young to have experienced the show the first time around.

Friends co-creator Marta Kauffman told Vulture in 2016 that her then-17-year-old daughter was asked by a school friend, “Hey, have you seen this new show called Friends?” The same article quotes anxious college students who swear by the show to soothe them to sleep. It’s a relationship that isn’t shared by other massive and still-popular shows of the era, such as Frasier, 90210 or Seinfeld. Kauffman can’t work out the specifics of the deep attraction for a generation that wasn’t yet born during the show’s original run. “It blows my mind,” she admits.

While it is, indeed, mind-blowing, it does also make a certain sense.

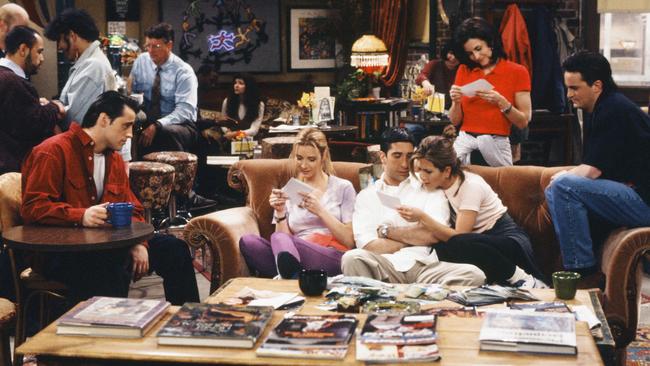

With a 10-year run that extended from 1994 to 2004, Friends is current enough that, wacky fashion choices aside, it seems to take place largely in contemporary society. It is, however, a Sliding Doors-style scenario, in which social media was never invented. And boy, does it seem simpler. There are no screens (unless you include the TV that Joey and Chandler once scored free cable porn on), no trawling Tinder for sex and maybe love, no nervous monitoring of Twitter followers, no posing for photos of experiences only half-experienced to upload to Instagram, no mindless scrolling. There is no FOMO as they are all in the same room, at the same time, experiencing the same thing, for the majority of the show’s run. To a busy, distracted generation also being sold on the importance of mindfulness exercises, Friends effortlessly embodies the idea of being here now. Sit, talk, listen, pay attention. Experience. Monica might be neurotic and controlling, but you cannot argue she isn’t 100 per cent present when fretting about her life in Central Perk. (The same probably cannot be said for Joey.)

There is also a sense of permanence that exists within the world of Friends that must prove comforting to a generation with zero job stability, and endless romantic possibilities, where social standing is measured not by the depth of your friendships, but by the number of them, and the measurable manner in which they “like” the “content” of your “personal brand”.

These six friends spent 10 straight years basically hanging out together, at the same table, at the same coffee shop. IRL. That is, when they weren’t spending time at one of two apartments across the hall from each other. Again, IRL. The dorm-hall set up of their living arrangements — boys in one room, girls across the hall in another — must be comforting to those fresh out of home and thrust into similar college housing. The way they all spend holidays together instead of scattering off to various family obligations is comforting. That the show is basically built around friends who hang out and talk in person is a radical notion in a world where most communication occurs via phones. Breakups need to be done in person. Difficult talks and fights and flirtation need to be done in person. Meet-cutes are actual meetings. Phoebe might pretend to be her twin in order to softly break up with Joey in one episode, but nobody is being catfished or ghosted here. You have to face life. This is TV, but you cannot fast forward.

Of course, there are other people in the Friends universe. A number of temporary lovers permeate the group for multi-episode arcs, but these characters seem as transient as a railcar hopping beat poet. The Paul Rudds and Bruce Willises might pop into Central Perk and shake up the snow globe from time to time, but when things settle, the original six remain, on the same couches, drinking the same coffee. There is comfort in how this group had chosen each other in their early 20s, and seemed content in their own exclusive company. (Ross’s Facebook page would show he has five friends.) There is comfort in the fact that no episode is titled The One Where Rachel Boredly Scans Her iPhone (and attempts to juggle a Tribeca loft party, two Tinder dates, and drinks with a school friend who keeps tagging her on Instagram).

Even the lasting romances are found within this sextet. Monica and Chandler found love with each other in the season four finale and became the show’s most enduring couple, if not the most endearing. Ross and Rachel — despite spending a mere 34 of the show’s 236 episodes as a couple, and having no real chemistry, or shared interests or viewpoints to speak of — were the show’s romantic centre; their permanent impermanence or their will-they-won’t-they even seems stable. There is as overriding sense that it’ll all work itself out, even if it’s hard — which in Trump’s America (or Zuckerburg’s America depending on how you view the world) must be very comforting.

Mention must be made of how archaically un-PC the show is with its gay jokes, trans jokes, fat jokes, the whitest gathering of humans since the crowds at ’80s Boston Celtics games and mild sexual-harassment-as-courtship. This might now be the subject of numerous revisionist articles about how “problematic” the show is (including this one, written by me), but for a generation who can literally destroy their career prospects and social circles with one misguided tweet, this notion of speaking unchecked must seem quite anachronistic and radical. I’m not suggesting Gen Y wants to be offensive or exclusive for the sake of it, but having to scan every thought for its perceived degree of “wokeness” can prove tiring. I suspect that Trump’s main attraction to voters wasn’t the content of the outrageous viewpoints he was expressing, but that he expressed them at all — and seemingly without comeuppance. Trump is leader of the free world. Chandler called Monica fat for years, then fell into bed with her. Neither learned a lesson.

Of course, for all that is unfamiliar about the show, it is the universal themes that have secured its place with the younger generations. The same realities about the 20-somethings in Friends ring true to 20-somethings of today: navigating unfulfilling jobs, dead-end relationships, crushes on friends, money issues (a particularly good episode pits the more affluent of the three against the poorer after the latter make a stand against the group’s bill-splitting practices), feeling too small for a big city, and leaning heavily on your close friends when you are down. These are the timeless qualities of the show, and why all the technology in the world won’t make it any less relevant. As the theme show expounds, the six friends are there for each other — physically and emotionally, when times are hard. In the sterile world of 2018, this type of relationship feels like a revelation and a revolution. It seems warm and inviting and non-judgemental. And Rachel’s hair will never not be fantastic.

- Nathan Jolly is a Sydney-based writer who specialises in pop culture, music history, true crime, true romance and where the old Australia’s Wonderland rides are now. Follow him @nathanjolly