These are the places across Australia people will soon struggle to live in without serious challenges

Roads melting, power supply dropping off and days reaching 50C — this is the bleak future Australia faces. So, how will your home town change?

Crushingly uncomfortable conditions, a greater risk of illness, economic turmoil, the destruction of ecosystems, extreme weather and ferocious bushfires.

It sounds like the description of some fictional dystopian society, but this is the stark reality that could face many Australian communities in the not so distant future.

Climate change is here and the consequences, both now and ahead, present significant challenges to all aspects of life, says Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, senior lecturer and ARC Future Fellow at the Climate Change Research Centre at University of NSW Sydney.

“The impacts of climate change are far reaching, from losing our precious Great Barrier Reef to the loss of life because of intense heat and bushfires,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

“Our way of life will be affected, as well as our economy and unique environment.”

Today, news.com.au launches its series Time Is Now, focusing on how climate change impacts Australians’ way of life. The series draws on the insights and extensive research of scientists, in special partnership with Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas and the Australian Science Media Centre.

To illustrate the impact, these are some of the regions that will become difficult places to live.

WESTERN SYDNEY

The western Sydney region has grown rapidly over recent years and is projected to be home to an extra 1.5 million people by 2056.

At the same time, average temperatures and the number of heatwaves are rising, and the types of new suburbs popping up aren’t designed to withstand harsher future conditions.

RELATED: Climate change myths debunked

RELATED: Truth about the world’s 12-year deadline

“We’re creating an urban nightmare in the west,” says Dale Dominey-Howes, a professor of science at the University of Sydney and an expert in hazards, disasters and risk.

Hotter days – and for longer – aren’t just uncomfortable. The impact of heat and heatwaves can be serious and western Sydney is vulnerable to a number of natural hazards.

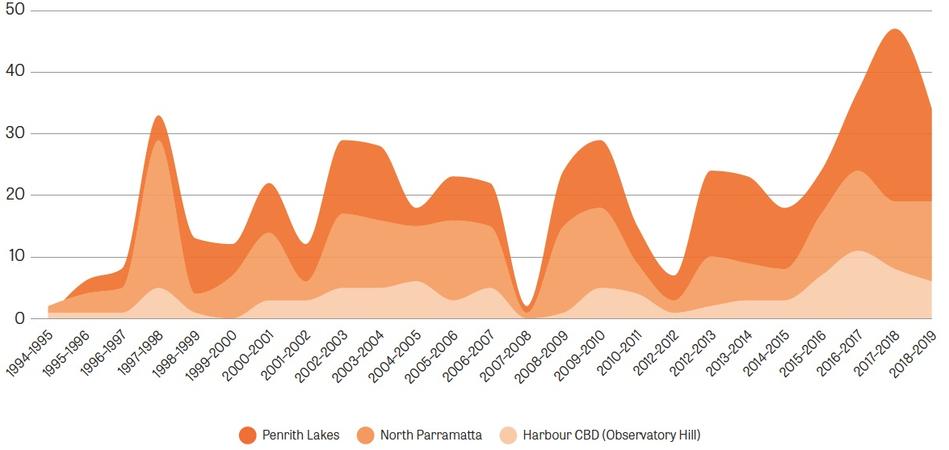

Western Sydney is set to warm by 1.5C to 3C by the end of 2050. Already, the number of days over 35C has almost doubled in 25 years – and that number is predicted to jump.

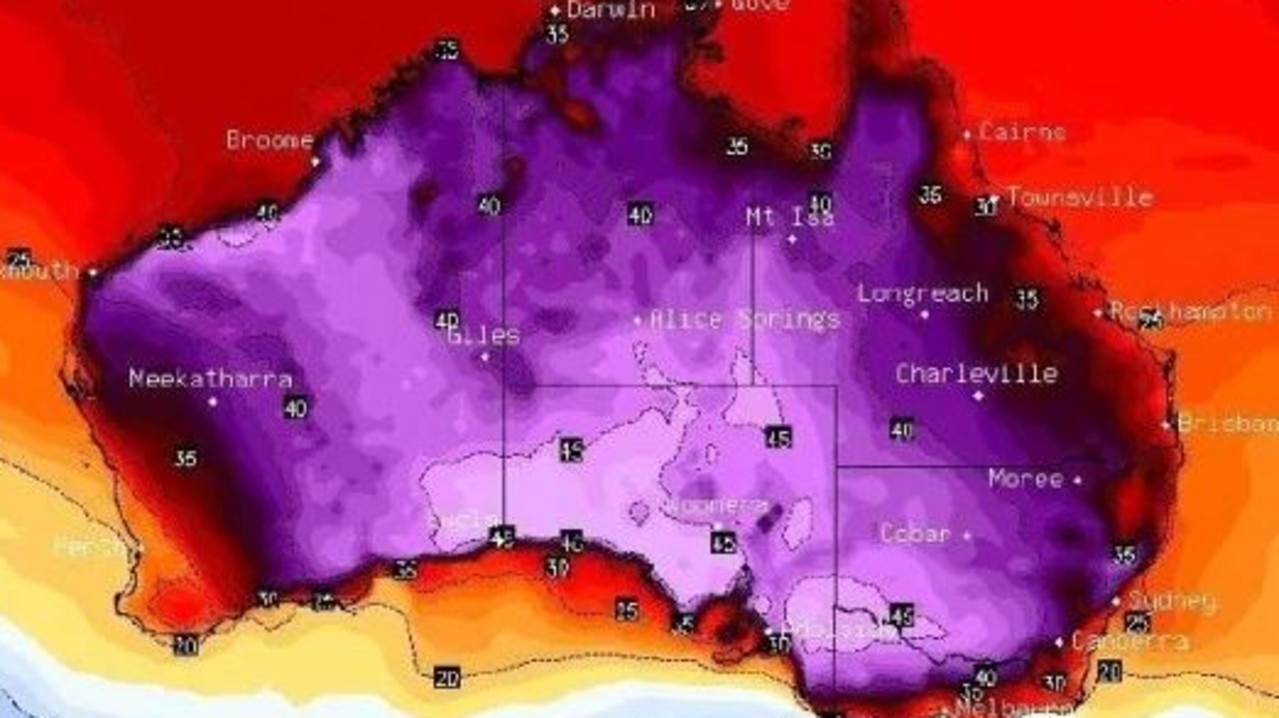

“It’s likely we’ll see days where the temperature reaches 50C in western Sydney by 2050,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

At that temperature, heatwaves can do things like melt roads and pathways, interrupt baseload power supply and make it less efficient.

And then there’s physical stressors on humans and animals, Prof Howes said.

“For humans, you start by getting overly hot, sweaty and uncomfortable. As the temperature rises starts to affect your concentration and decision-making. You might do things that are more dangerous,” he said.

RELATED: The things we’ll lose forever

“At the threshold of 41C, critical internal organs – the heart, liver, kidneys and so on – start to function more poorly. Once past that critical threshold, they can actually start to fail and death is more likely to occur.”

Going about your daily activities, both at home and work, would become increasingly difficult and this would have a ripple effect across the economy.

“In addition, we know that hospital admission rates already rise dramatically during heatwave events because heat exacerbates underlying health condition,” he said.

“Sick, young and older patients are particularly vulnerable. But as we move forward, that demographic could expand to include groups currently otherwise considered healthy – individuals from 15 to 55. So, heat and heatwaves increase the burden on the health system.”

Heatwaves can increase the amount of atmospheric pollutants, making it harder to breathe and increasing risk of harm to lung and heart systems.

“We’ll have to change the Australian attitude to heat,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

“We can’t afford to discount the risks. Sucking it up, saying ‘she’ll be right’ and having a barbeque, won’t be possible down the road.

“We can’t be complacent about the impact of heatwaves in the future. This will be worse than what we’re used to, what we’ve experienced in the past.”

Heatwaves are silent killers now at it stands, but their death toll is likely to rise in the future.

“Now, more people die from heat on January 27 than any other day because millions of us are outside celebrating Australia Day (the day before), where exposure to heat and the presence of alcohol create a deadly combination,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

But the risk is present throughout the year, with heat killing more Aussies than all other natural hazards combined annually.

The Black Saturday bushfires are considered Australia’s single greatest loss of life in a disaster, claiming 173 lives.

“But the heatwave preceding it killed at least 374 people in Melbourne alone. Some estimates are that it could be closer to 500 people,” Prof Dominey-Howes said.

Overall, the heatwave that rolled across the country and ultimately set the stage for Black Saturday, might have hospitalised up to 2000 people in Melbourne.

The consequences in a region like western Sydney is made worse when you examine the types of dwellings many people will occupy.

New housing estates filled with big dwellings constructed of cheap and dark materials on small blocks with minimal foliage, on streets with minimal tree cover, are suboptimal.

“Homes should have wide open spaces, decent distances between buildings for airflow, orientations that avoid absorbing heat, types and colours of materials that don’t attract heat and radiate it back out at night-time, and have a number of trees for shade and temperature control,” Prof Dominey-Howes said.

“Unfortunately, that’s all lacking in many of these western suburb planned estates.”

SOUTH WEST AUSTRALIA

The future situation in south west Australia paints a similarly stark picture.

This region will experience less rainfall, leading to drier conditions, ultimately affecting the economy through lower wheat yields.

In the future the rainfall change could be up to 25 per cent less than what it is now.

“Basically it’s going to significantly decline,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

“The weather patterns that bring rainfall to south west Australia are contracting towards the poles, or shifting south, particularly during winter, which is when the region receives the most amount of rain.

“A place that’s already reasonably dry is going to get drier, with implications for agricultural production, wine production and tourism.”

In inland areas, frost days have increased by about two to four weeks, mostly because of clearer skies at night.

“That can have massive effects on what you plant and when you plant it,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

Agricultural water supplies have already decreased by up to 25 per cent.

Wheat yields have stagnated since 1990, in part due to changes in the climate, in an industry worth more than $5 billion a year.

“Rising temperatures and reduced rainfalls are responsible for the shortfall in wheat yields,” she said.

By the end of the century there could be up to 20 to 30 heatwaves days in a season, compared to five to 10 now.

“The number of heatwave days has increased significantly and they’re getting longer and hotter. The change isn’t as dramatic as other cities but it’s still there.”

FAR NORTH QUEENSLAND

The Great Barrier Reef is one of the world’s greatest natural wonders and contributes much more to those living nearby – and all Australians – than a picturesque part of our geography.

The net social, economic and iconic value of the Reef has been estimated at $56 billion per year. The Reef directly supports 64,000 direct and indirect jobs and contributes $6.4 billion to Australia’s GDP.

It’s critical nationally, but especially to the Far North Queensland region where thousands of people rely on it for employment, and countless other businesses need it indirectly for their future prosperity.

But it’s in serious trouble because it’s threatened by multiple intersecting climate and weather-related processes, and the impacts of inappropriate land management.

“A temperature increase of 2C will completely change the reef as we know it,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said. “It’s very difficult to see how we don’t get to that point in the future.”

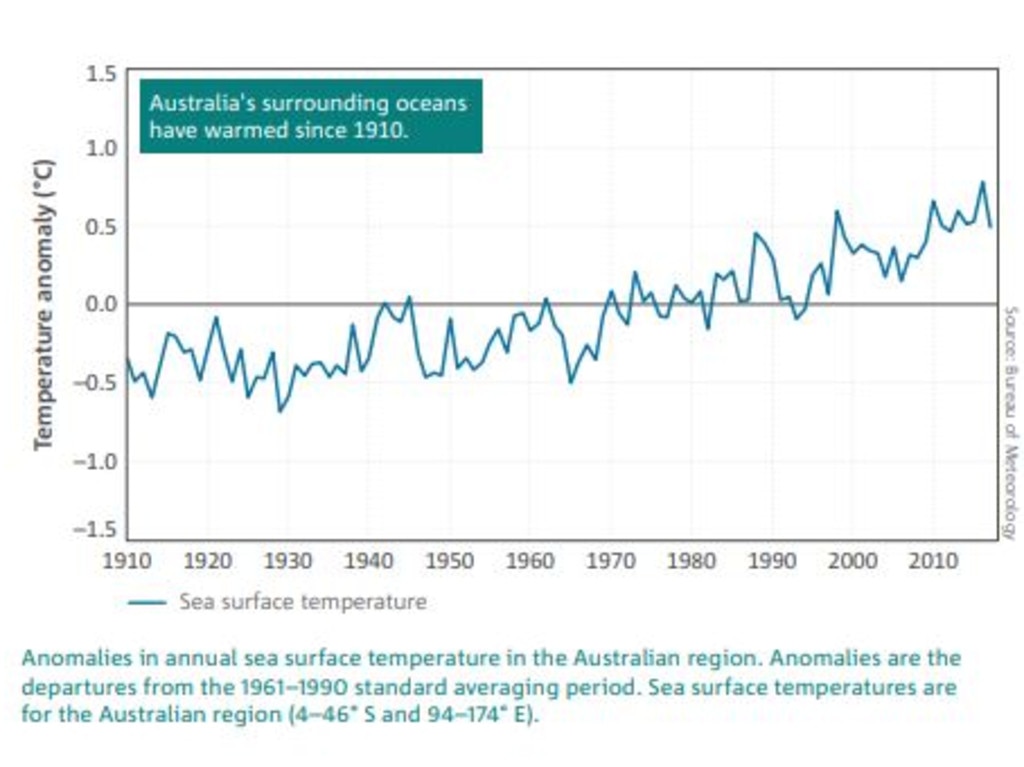

Coral bleaching has occurred in the past on the Reef, but it’s happening with dramatically increased frequency and extent over recent decades due to warmer ocean temperatures.

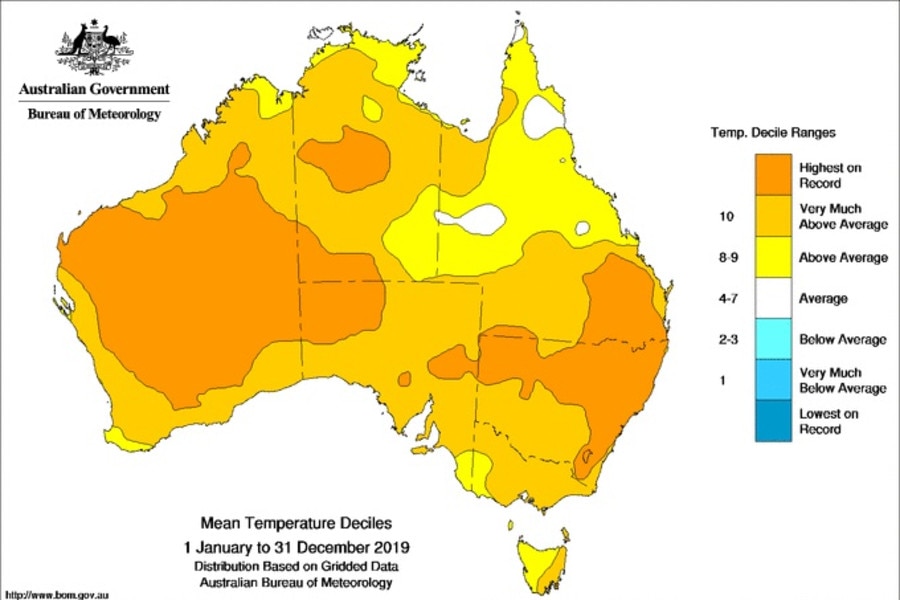

The CSIRO Oceans report State of the Climate 2018 found there was a 0.16C temperature increase per decade since 1950.

That increase appears to be accelerating, which will contribute to more severe and more frequent coral bleaching events, Prof Dominey-Howes said.

“The time to recover has gotten shorter and so the chances of a full recovery are impaired.”

It’s a stark reality already being seen, with a bleaching event in 2016 resulting in a staggering 93 per cent of the reef being damaged.

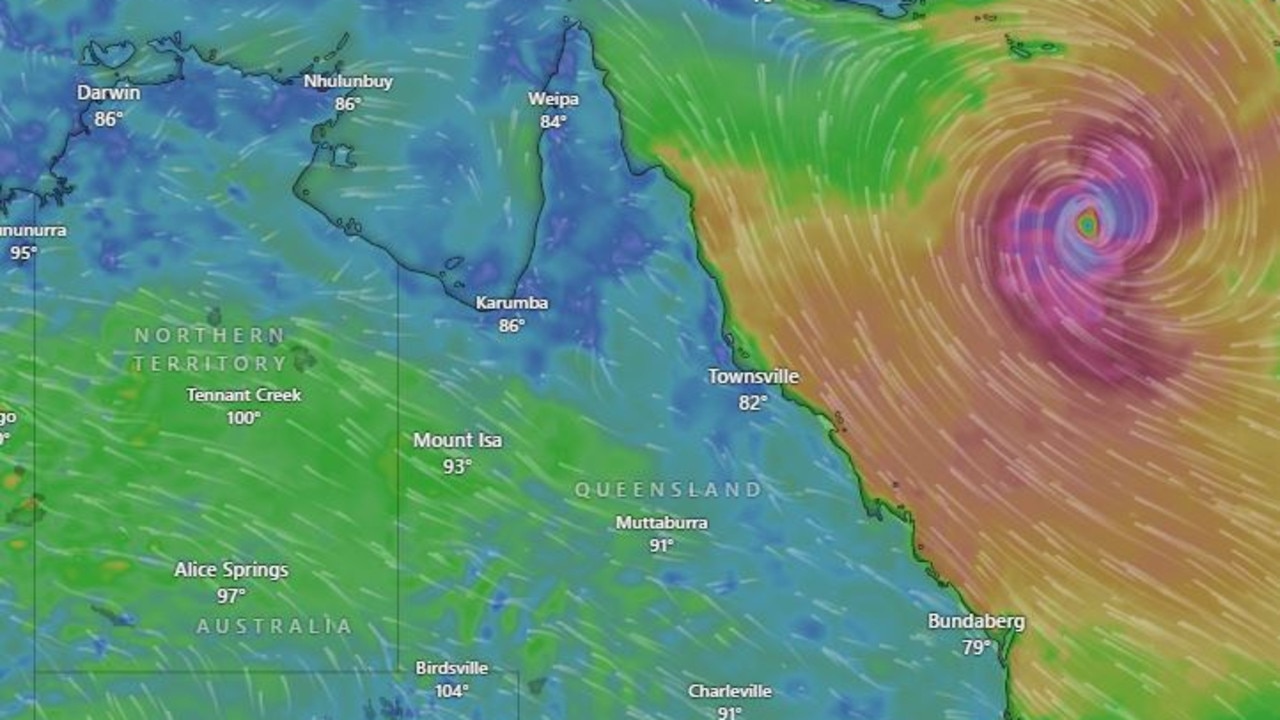

The Reef is also at threat from an increased acidification of the oceans, as well as the likelihood of increased tropical cyclone frequency and intensity.

“As the ecology of the reef changes, it can favour invasive pest species. Other plants and animals not traditionally there can come in and out-compete the natural ecosystem,” Prof Dominey-Howes said.

“Coupled with that, the washing off of sediments and other debris from the land due to poor land management practices.”

A temperature rise of 4C would destroy the Reef entirely – a scenario that’s not impossible if action on climate change is delayed or below current commitments.

“We’re struggling to keep temperature rises at 1.5C to 2C, so further increases will be extremely damaging to the reef, it’s health and diversity and productivity,” he said.

Once it’s gone, it’s gone forever and the loss will be more devastating than a pretty picture, with entire communities in the north potentially paying the price.

SOUTHEAST AUSTRALIA

Over the past few months, Australian witnessed hell on earth as large chunks of the country – particularly in the southeast – were razed by ferocious bushfires.

There’s a very good chance we’ll see such destruction again in the near future, again and again, with greater intensity and frequency.

Once again, southeast Australia will be in the firing line.

“This is happening under 1C warming,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said. “Under 2C to 3C warming, we could see bushfire seasons that are even worse.”

Bushfires aren’t a new challenge in Australia and the most recent fires, which affected three-quarters of all Australians, would have occurred without climate change, Sarah said.

“But they wouldn’t have been as severe,” she said.

From 1973 to 2010, the fire season in Australia’s southeast has lengthened and it’s projected to continue to do so into the future.

“It means there’s less chance for hazard reduction because the conditions to do those burns occur during a shorter window now,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

Intense fires, known as pyrocumulonimbus systems, interact with the atmosphere and create their own weather systems. They are more conducive in warmer environments, she said.

“The time between these ferocious fires has halved. Historically, we usually saw one or two a season. In the current season, we’ve seen 20 to 30.”

Australia’s southeast stretch is where most of the population lives, she pointed out, “and so the exposure of people and buildings is the highest”.

“We will have to seriously shift our approach to a number of critical areas, from the design of homes and their locations to bushfire management plans,” Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said.

“We will also have to change what we farm and how we farm it, and that’ll have knock-on effects to the broader economy and cost of living.

“In addition to agriculture, bushfire seasons of the future will also impact a number of southeast Australia’s vital sectors, including tourism and viniculture.”

SOUTHEAST QUEENSLAND

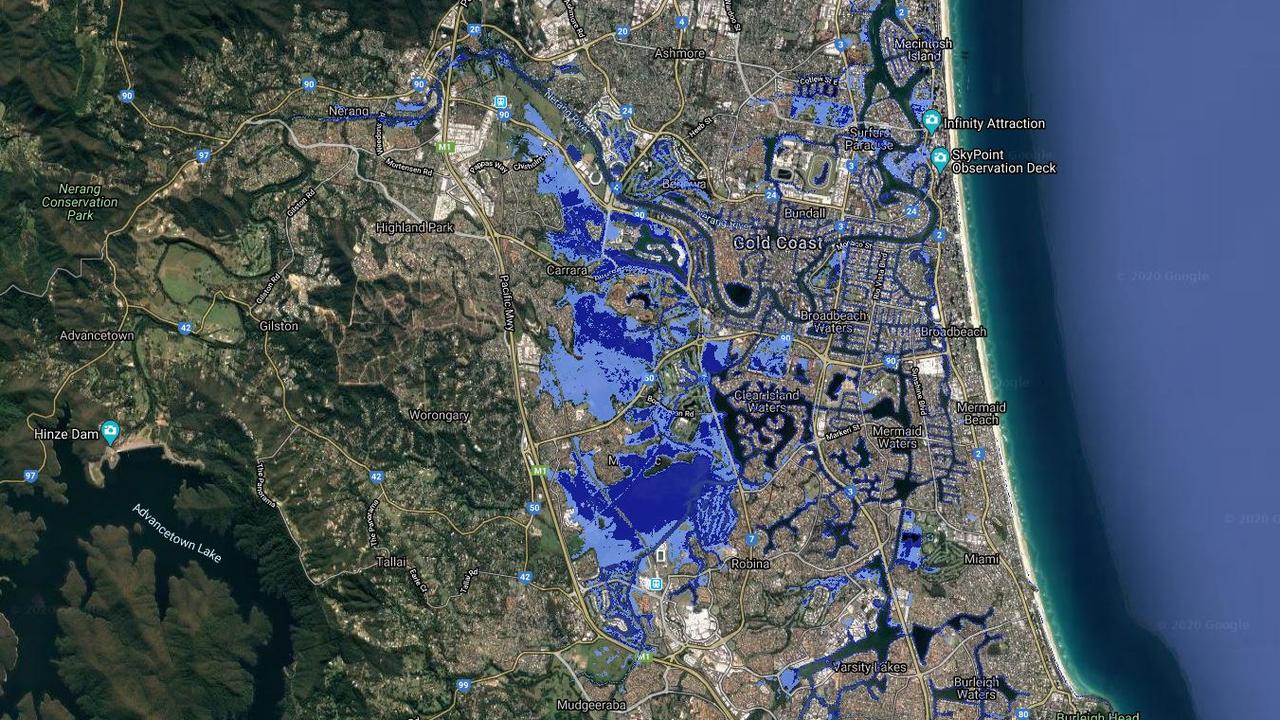

In 2019 the Queensland department of environment warned a sea level rise of 1.1m would cost $226 billion nationally by the end of the century.

Southeast Queensland is the hotspot for sea level rise risk, with an estimated 68,000 homes at risk of destruction.

Prof Dominey-Howes said there were several interacting factors that created this risk.

“In a warming world, each additional 1C rise means the atmosphere holds an additional seven per cent of water, which has got to go somewhere, so when storms happen, the forecasts are for increasingly intense rainfall events,” he said.

“If there are storms, then we have other processes that happen – we can have a storm surge and then you might get wave sets on top of that.

“So that means the extreme water level for future storms, under a climate change world, puts even more property at risk. The increasing risk threatens the sustainability of those communities.

“This has been a high growth corridor where a lot of people have been encouraged to settle, which increases the exposure above what would have otherwise been the case.”

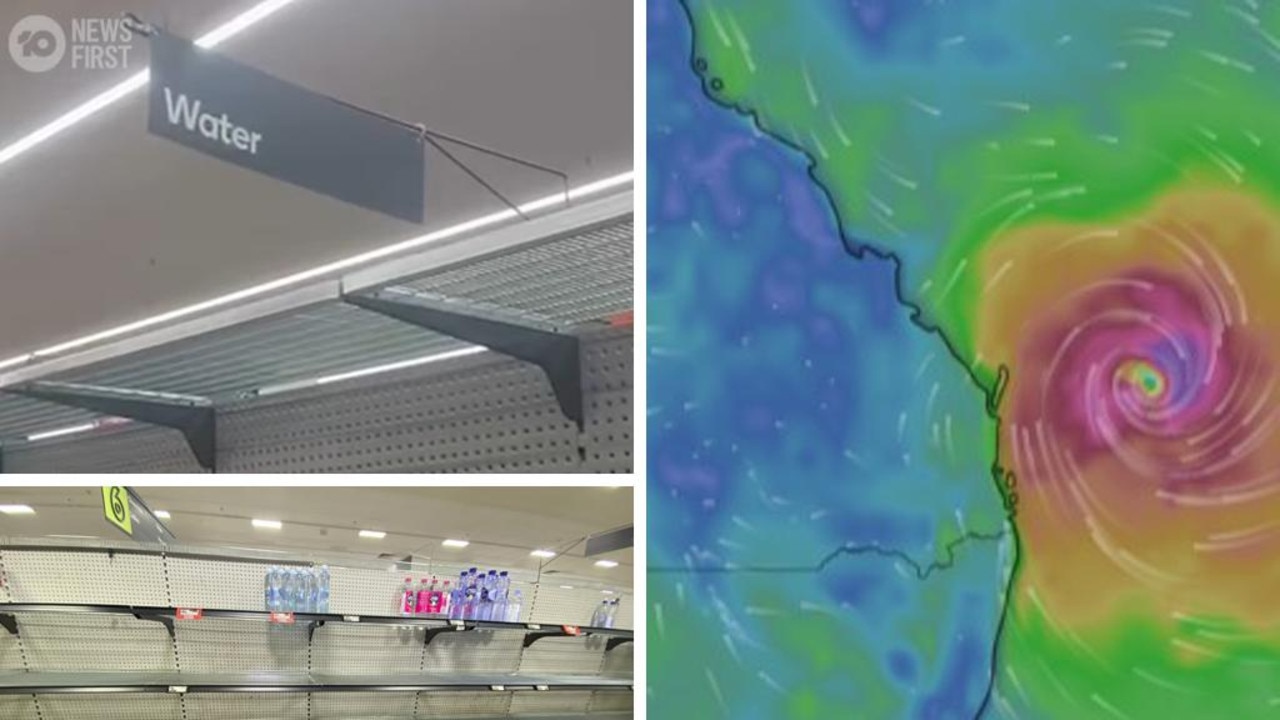

The conditions that favour tropical cyclones are also more likely in southeast Queensland in the future.

“There is concern tropical cyclones could make their way further south,” Prof Dominey-Howes said.

With populations in the city rapidly growing, he said there would be more people and property at risk.

Tourism is now worth $4.65 billion annually to the Gold Coast’s gross regional product and employs 42,000 people, with 20 per cent growth year-on-year.

“Climate change has the real potential to curtail that growth in value.”

IS IT TOO LATE?

Conversations about how Australia should respond to the challenges of climate change – or, as some continue to debate, whether we should at all – continue to rage.

But Dr Perkins-Kirkpatrick said it was critical for everyone to understand that it’s “never too little or too late to reduce our carbon emissions”.

“Everyone plays a part and no part is ever too small. We should never become complacent in our efforts to reduce our emissions now or in the future.”