Tokyo Olympics: Australian reporter mistaken for sex offender at Sydney airport

An Aussie reporter heading to Tokyo on his first flight since the pandemic hit was terrified after being mistaken for a sex offender at Sydney airport.

“Can I see your passport, mate?”

Words you expect to be uttered at an airport, but not ones you want to hear after you’ve already cleared the check-in counter, passport control and had your carry-on baggage given the green light.

It’s even worse when you hear them just metres from the gate where you’re going to wait for the boarding call ahead of your first international flight in 18 months – your first overseas trip since Covid-19 became part of our vocabulary.

No traveller has ever been chased down and asked for their passport at that point in their journey so they could instead be whisked off to an island paradise where their first Hollywood crush is waiting for them holding coconuts and wearing nothing but a sarong. So I sensed bad news was coming.

Two beefy Australian Border Force officers working at Sydney airport flanked me as they asked the question. They looked at my passport, jumped on the phone, then told me to come with them. Asking what this was all about as I walked nervously back to where I’d just come from, I was simply told: “It’s a Federal Police matter.”

Fantastic.

As a reporter heading to Tokyo for the Olympics, I was carrying 87 pieces of paper in a plastic-sleeve folder – many of them double-sided. Accommodation details, vaccination certificates, insurance letters, flight tickets, press packs, contact lists – they were all there after being checked at least 27 times in the days before my departure.

Despite the lack of fellow passengers on my flight, the check-in process was long and tedious as I pulled pages out of sleeves and showed airport staff emails I’d received just an hour earlier confirming I was Covid-negative. I thought – wrongly – I’d finally reached the point where I could zip my backpack up for good until I strolled on board.

Walking back to God knows where with the Border Force officers, one asked: “You were taking a lot of photos of McDonald’s back there. What was that all about?”

It’s true. Even in a pandemic I thought, ‘If Macca’s is closed, then the world really has gone to s**t’. The airport was basically deserted.

I’d been taking photos on my phone of hauntingly empty corridors – something I’d never experienced at Kingsford-Smith in my decade of international travel. My editors wanted insights into what it was like being one of the lucky few Australians allowed to head overseas – and snaps of an empty airport were as good a place as any to start, I thought.

My voice wavered as I explained this to the men in thick navy uniforms and heavy, black boots, all the while trying to sound like an innocent man. Because you’d never arrest someone if their small talk was on point, right?

Now all I could think was: “A photo of a closed McDonald’s is going to cost me a trip to the Olympics, and put me on a no-fly list for a while too. Why the hell did I choose this moment to start my amateur photography career?” And just as confronting, how was I going to explain this to the bosses?

I was back at passport control and told to sit on a row of empty seats. My passport, boarding pass and phone were taken from me. Soon a different Border Force officer asked if I’d ever had anything to do with the police.

I’d given a statement once, about 10 years ago following an incident involving patrons at a pub I worked at. But I’d never been arrested or had any trouble with Johnny Law. The officer seemed surprised. I wisely decided this wasn’t the time to tell him I was planning on bingeing cop drama Line of Duty during hotel quarantine.

I’d been on edge all week and the feelings magnified en route to the airport, anxious about something going wrong – missing a piece of paper here or having the wrong box ticked there. One mistake was all it would take to prevent me from hopping on a plane. Sitting alone while serious-looking men and women gathered in a huddle around a computer terrified the bejesus out of me. I can’t remember being more afraid – other than meeting my girlfriend’s parents for the first time.

Another journalist from my company passed through and introduced herself after recognising me. I wasn’t sure if I was allowed to talk to anyone, so I rudely shooed her away. The officer who first stopped me in my tracks hurried over, asking what was going on. I was told to sit tight.

This was all happening about an hour before my flight was due to take off. I was a mess. I’d taken a few photos on my dodgy phone – were they looking to see why I was scoping out an airport? If I promised I wasn’t a terrorist, would they believe me? Or is that exactly what they’d expect a terrorist to say? Reverse psychology is a complicated mistress.

I sat in silence, rubbing my hands in a nervous tick kind of way, then telling myself not to because only guilty people act restless like that.

About 20-30 minutes had passed since I was first stopped – I think – when the original officer came walking towards me with my phone, passport and boarding pass. He handed them back and apologised.

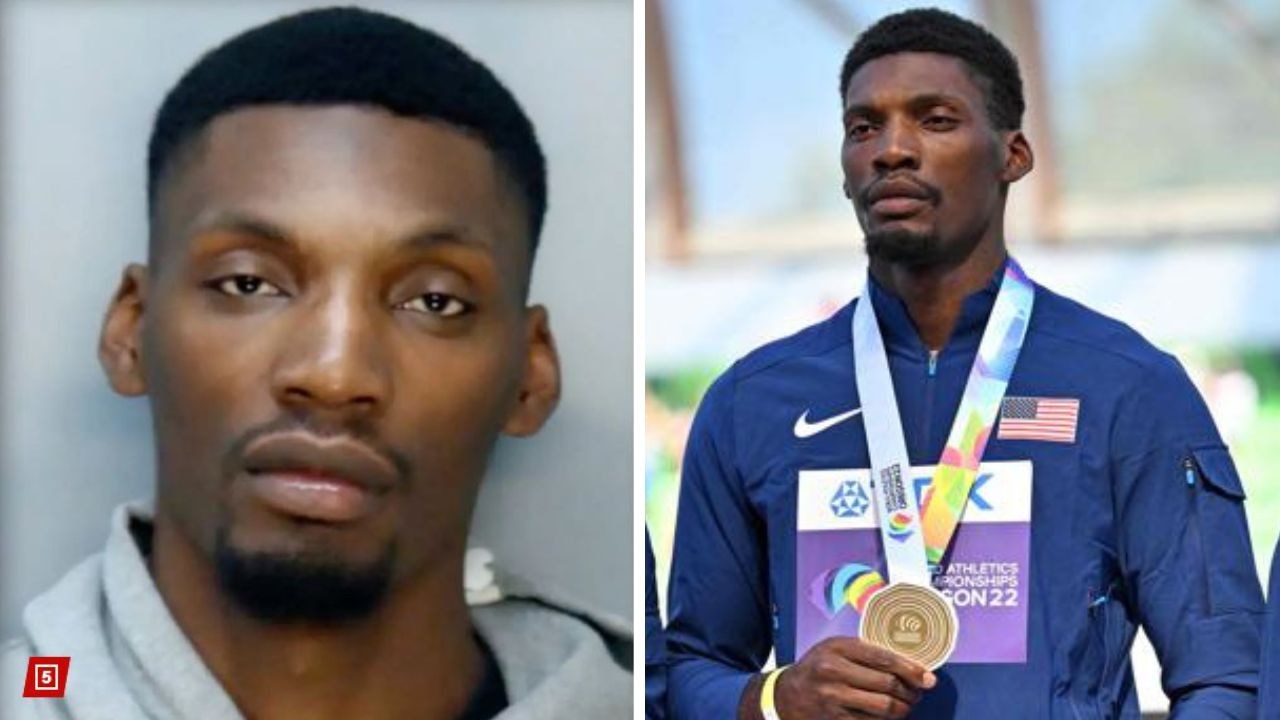

Apparently the details on my passport were a 96 per cent match for someone else who happened to be a registered sex offender. Something in my date of birth, passport number and issue/expiry dates was apparently remarkably similar to a person the Australian Federal Police had more interest in than me.

The red flag was raised but thankfully, photos of McDonald’s with the lights off and an empty queue at customs weren’t going to be the end of me.

These Olympics were always going to throw up challenges like never before, but being mistaken for a criminal before takeoff was paying longer odds than the Wests Tigers to win this year’s NRL premiership. It was time for a beer.

James Matthey is news.com.au’s sports editor. Follow all his Olympic coverage here