‘It’s a total fantasy’: First sign all is not right in Paris

A glimpse out the window of a Paris cafe on the day Olympic action began was provided an imposing reminder - this is a city on edge.

Rio had a race to complete stadiums. Tokyo a Covid crisis. But neither endured the disunity and destruction that has plagued Paris in the lead-up to hosting the Olympics.

The 2024 Games will be held in a country at war with itself following waves of anti-government riots, growing tensions over immigration, religion and race, terrorism fears and the rise of the far right over the past 12 months in France.

Anne Hidalgo, the Mayor of Paris, has said the city’s bid for the 2024 Olympics was seen as an opportunity for the French capital to rebound and heal following outrage at the 2015 Islamist terror attacks that left 130 dead.

“I said to myself that things were really, really, really bad, and that we absolutely had to find something that also provides perspective, momentum, to young people, to the country,” Ms Hidalgo told Euronews last year.

“And the Games can be this unifying moment.”

As Olympic action officially began on Wednesday with Rugby 7s games, it was clear this is a city on edge.

As tourists ate croissants and sipped on coffees at breakfast, soldiers armed with assault rifles patrolled the streets. It’s clear Paris is not taking any risks as it prepares to showcase its best side to the world.

‘Total fantasy’

But can the Olympics do the impossible and bring the fractious country back together?

“No,” said Dr Tom Heenan, lecturer in sport and Australian studies at the Monash University.

“It’s a total fantasy. You get a feel-good effect in cities but the divisions are too stark.”

Over the past 18 months, France has been rocked by a series of riots sparked by issues including pension reforms and the police shooting of a 17-year-old, ongoing farmers protests causing chaos as tractors blocked major roads, and even the defacement by environmental activists of the iconic Mona Lisa at the Louvre.

Just last week, a French soldier deployed in the anti-terrorism force was stabbed while patrolling at a train station in central Paris by a 40-year-old immigrant from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who reportedly shouted “God is great”.

The attack on Monday evening, a week-and-a-half before the Opening Ceremony, put the city on edge and again shone the spotlight on immigration, which has emerged as one of the top concerns among French voters.

And over the weekend, an Australian tourist was allegedly gang-raped in the city’s 18th arrondissement, metres from Moulin Rouge.

Snap parliamentary elections earlier this month saw Marine Le Pen’s anti-immigration National Rally thwarted in hopes of an outright majority, after a broad coalition of left-wing parties co-ordinated with President Emmanuel Macron’s centrists to strategically withdraw candidates in more than 200 seats to give the anti-National Rally vote a better chance.

The result was the New Popular Front, a coalition of Greens, Socialists, Communists and the hard-left France Unbowed, gaining the largest number of seats in the National Assembly, with 193 of 577, but well short of the 289-seat threshold for a majority.

Ensemble, the centrist coalition led by Mr Macron’s Renaissance party, holds 164 seats.

But Ms Le Pen’s National Rally and its allies still made undeniable progress, growing from 89 seats in 2022 to 143 today.

Victory “has only been postponed”, she told reporters as she visited parliament earlier this month, complaining that what she dubbed “massive withdrawal manoeuvres” had “deprived us of the absolute majority”.

“The elections have done nothing other than to say France is more divided than ever,” said Dr Heenan.

“Whatever the IOC says about the Games bringing people together, the divisions in society still remain. You’ve already had the bussing out of homeless people from the city centre. What Olympics really do is they create hyper-security and hyper-militarisation of cities. That doesn’t reflect any unifying factor at all, it’s actually to cover up the divisions within the city.”

The results of this month’s vote came as a relief to those who were worried about the rise of the National Rally, which has seen surging support amid public concerns over immigration and crime, but whose candidates had been accused by opponents of pushing racism and xenophobia.

France’s media watchdog said this month it was fining popular 24-hour TV channel CNews over a journalist who did not challenge a guest who said “immigration kills” during a discussion on National Rally last December.

Sport and the far-right

The country’s ever-present tensions over race, stemming from its colonial past in Africa, are inextricably woven into sport.

During the election campaign, French football captain Kylian Mbappe issued a plea to the public to recognise “the extremes are knocking on the doors of power”, urging young people to “make a difference” and “shape our country’s future”.

“I don’t want to represent a country that doesn’t correspond to my values, that doesn’t correspond to our values,” he said.

His teammate Marcus Thuram went further, explicitly urging the public to reject National Rally, describing the right-wing party’s leading position in the polls as “the sad reality of our society today”.

“We must tell everyone to go out and vote,” he said. “We all need to fight daily so the National Rally does not succeed.”

A quarter of a century ago, Ms Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, leader of the Front National, as the party was then known, famously downplayed France’s 1998 World Cup victory, which was widely hailed as a triumph for multiculturalism with players including Lilian Thuram, Patrick Vieira, Zinedine Zidane and Thierry Henry.

“It’s a bit artificial to bring players from abroad and call it the French team,” he said at the time.

Mr Le Pen, who was expelled from the party by his daughter in 2015 for anti-Semitism, continued to make similar statements over the years about the ethnic makeup of the French football team, including that “France does not fully recognise itself” in the 2006 World Cup squad.

“The tension between sport and the right-wing nationalists goes back to the end of last century and it’s still going on,” said Emeritus Professor David Rowe, a researcher at Western Sydney University’s Institute for Culture and Society who has published numerous academic works on social impacts of the Olympics.

“Jean-Marie Le Pen said these people do not represent France, they are not French enough. There’s still this issue. The right says these people aren’t French. The migrant communities say we are not being accepted as French, we can never be French enough because we look wrong, or we believe in the wrong religion. Part of that is France’s difficulty reconciling itself with its colonial past. Many people don’t want to.”

He added, “The Olympics, is it expected to magically resolve these problems, reconcile these differences?”

France’s surging right-wing, which “took great exception to Mbappe saying vote against the right”, have “had to play a bit more careful game with the Olympics’.

“But there certainly have been the same kinds of statements about who actually represents France and the same hostility,” said Prof Rowe.

“It tends to come down to women who wear the hijab.”

Dr Heenan said it would be “highly unusual for anyone on the far-right not to use the sporting event” to drive their message.

“Fascists used it in Italy, Hitler used it in Berlin, the junta in Argentina used the 1978 World Cup,” he said.

“There is a connection between far-right politics and sport. When you look at the other side of politics, you’ll have the left defending neighbourhoods that are going to be impacted by the Games. One of those neighbourhoods is Bondy [where Mbappe grew up]. A really high percentage of top-ranking footballers come from that area in one of the poorer parts of Paris. That is an area where you won’t see the benefits of the Olympic Games trickle down.”

Simmering tensions

Prof Rowe said the return of the Olympics to Paris for the first time in a century, just after an election which “came uncomfortably close to installing a far-right, xenophobic government”, exposed France’s tensions over cultural diversity, immigration and colonialism.

The nation of 68 million people has the largest Muslim population of any country in Europe at 10 per cent.

French law prohibits collecting census data on ethnicity, but a 2008 academic study estimated the France’s population was 85 per cent white, 10 per cent North African and 3 per cent black.

In 2010, the French government sparked outrage from its Muslim community by banning the wearing of full face veils in public, and restrictions on wearing religious symbols such as headscarves have since been tightened further.

“There is a kind of perversity in the host nation allowing the veil to be worn by overseas athletes but not by their own,” said Prof Rowe.

“I think that is symbolic of the problem that France is having with dealing with having the largest Muslim population in Europe, and not reconciling itself [with these competing cultural tensions].”

Those tensions are also being felt more broadly in significant opposition among the French to hosting the Games.

“There is actually quite a lot of hostility to the Olympics themselves,” said Prof Rowe. “There are plenty of Parisians who just don’t want it.”

Saint Denis, one of the most famous multicultural suburbs in Paris, is the site of the athletes’ village which has been locked down with a massive police and military presence in three concentric rings of security.

“There has been the removal of poor people and people who might embarrass the tourists, closing down the squats where many such people live,” he said.

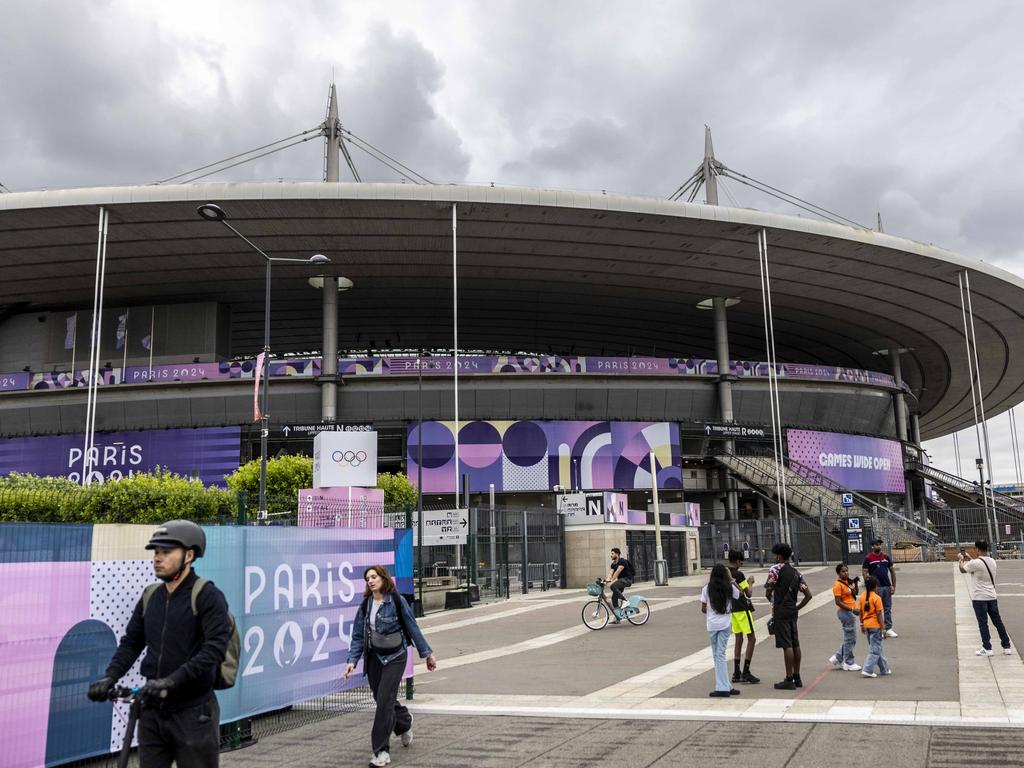

Prof Rowe said French authorities would be desperate to avoid a repeat of the 2022 Champions League final at the Stade de France in Saint Denis, where match-goers leaving the venue were ambushed, attacked and mugged by organised gangs.

“They had to walk a gauntlet, quite infamously, of the fans being attacked, gangs ripping necklaces off women as the police stood off,” he said.

“I think that indicates the kind of problems, the tensions [that exist]. In the poorer suburbs that are migrant dense, the relationship with police is appalling. That tension is just beneath the surface, then you add terrorism to the mix, of course itself connected to those tensions. There is a lot of concern about it, as there is for all major events, therefore you get a larger and larger political apparatus. It’s one of the reasons why hosting the Olympics is increasingly unpopular.”

‘White elephants’

Another reason is the debate over the economic benefit, or lack thereof, to host nations.

A report by state statistics body Insee this month said France’s economic growth would increase by 0.3 percentage points in the July-September quarter thanks to the sporting extravaganza.

That would be mostly down to “a rise in tourism” as well as sales of tickets and broadcasting rights which have been logged as activity in the period, the agency said, adding the Olympics would reduce growth by 0.1 percentage points in the final quarter of the year as some of the one-time effects are unwound.

The estimates were based on observed effects in London during and after the 2012 Games.

Measuring the economic gains attributable to so-called “mega-events” such as the football World Cup and the Olympics is notoriously difficult.

The construction work that precedes each Games helps to boost jobs and growth in the run-up, while extra foreign visitors and other commercial activity such as ticket sales and food and beverage consumption also help create wealth.

In some instances, however, the Olympics can suppress tourist activity, with high hotel and flight prices deterring some visitors, and consumer spending can be affected if people stay at home to watch sport in large numbers.

Many hotel chains and others involved in the Paris tourism sector have complained in recent weeks that visitor numbers are down in the French capital as regular foreign travellers stay away — with the Olympics effect compounded by bad weather.

France’s top airline Air France-KLM warned at the beginning of July that the Olympics would lead to a drop in revenues of up to 180 million euros ($291 million), saying there was “significant avoidance of Paris” internationally.

An economic impact study by the France-based Center for Law and Economics of Sport in May, which was commissioned by the organising committee, estimated the Games would generate an economic gain of up to 11.1 billion euros ($18 billion) for the capital region.

“The reason people bid for the Games is actually to redevelop cities, to bring in capital, and what it does is in many ways creates further division,” said Dr Heenan.

“It’s people in cities who really are the loser in this. You see it particularly where the Games have cost a lot of money and bankrupted cities — Montreal in 1976, Athens in 2004. We’re seeing similar things in Brisbane ahead of the 2032 Olympics.”

Dr Heenan said whether someone saw any benefit “depends on where you sit in society”.

“If you’re somebody in Woolloongabba who’s a renter, your future with the Olympics is looking quite bleak because that’s one of the areas that will be gentrified,” he said.

“If you’re a developer the Olympics are looking pretty good for you. It depends where you sit and how involved you are with the cabal that runs the whole thing. Most of society will just get that feel-good effect. Who walks out with the money? It’s basically the IOC.”

Every mayor or leader “says something like it’s a great thing to bring the nation together”, added Prof Rowe, who said the impacts were “multidimensional”.

“You can have big, urban infrastructure changes, it advances changes that would normally take decades,” he said.

“It can be good or bad, white elephants or useful infrastructure. But it’s also like a big, expensive party. Put it this way — it’s never as great and never as terrible as predicted by various interest groups.”

— with AFP