Nine amazing Indigenous Aussie sports stars you probably haven’t heard of (but should)

Cathy Freeman and Lance Franklin are national icons, but do you know these amazing, inspiring and occasionally bizarre tales of Indigenous sports stars?

Cathy Freeman, Patty Mills, Ash Barty and Lance Franklin are all household names.

In fact, many of Australia’s biggest sporting heroes have Indigenous heritage — an amazing fact in itself considering Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people make up 3.3 per cent of the population.

But there are many more incredible, inspiring and occasionally bizarre, stories of First Nations sporting talents that we all should know about. Here are a few.

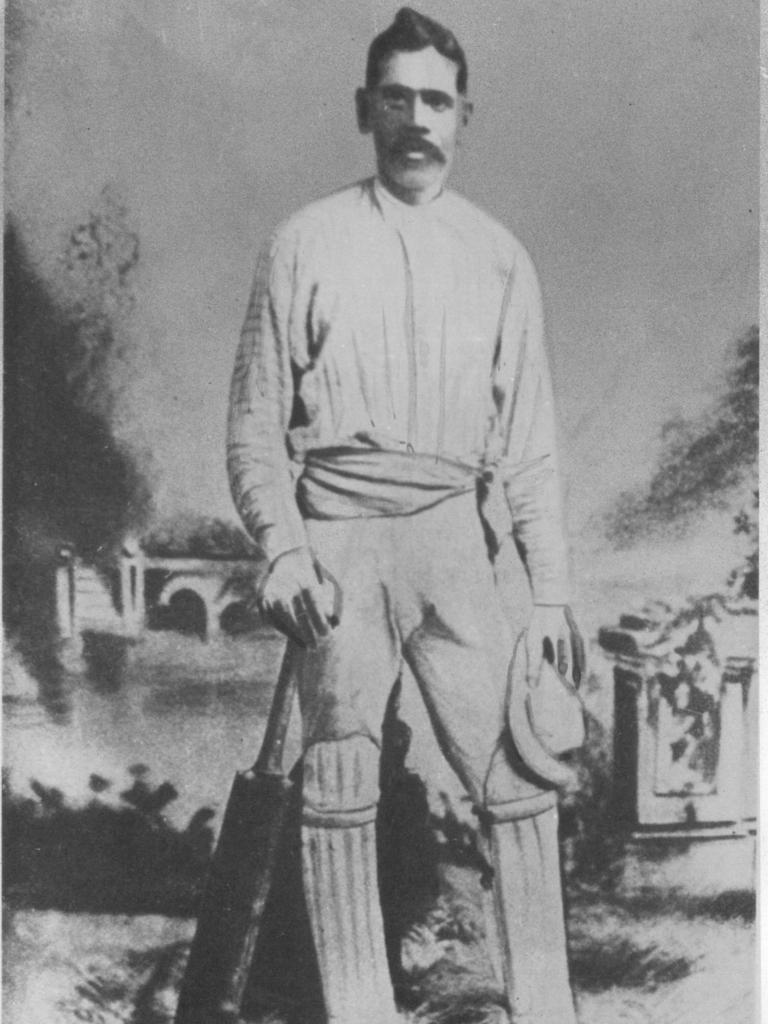

JOHNNY MULLAGH

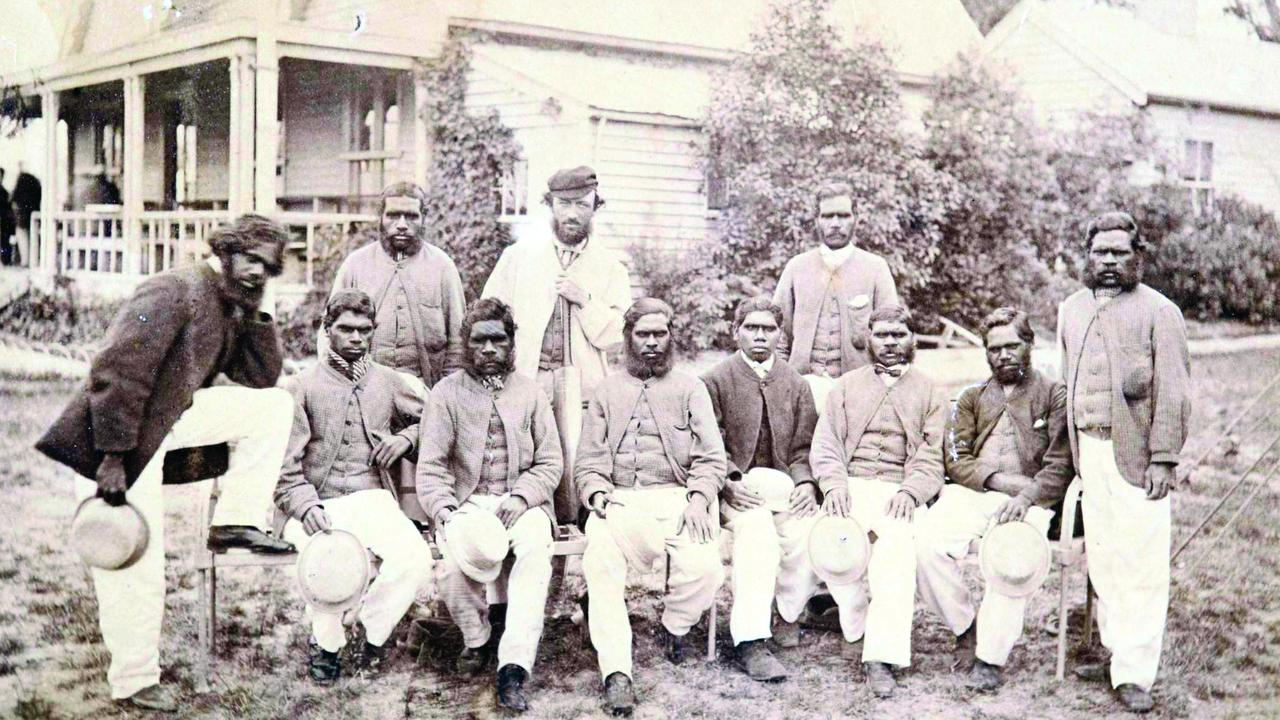

Mullagh was one of Australia’s first cricket champions and delivered what must be one of the great performances by any all-rounder. He was one of 13 Aboriginal players smuggled out of the colony to England in 1868 by squatter William Hayman and English ex-pat Charles Lawrence, the first Australian sporting team to tour internationally.

On one day in Burton-on-trent Mullagh topscored with 42, took 4-59, caught a fifth batsman and as wicketkeeper stumped the other five.

As well as being one of the stars of the cricket side, tour matches were enlivened with displays of Aboriginal athletic prowess; Mullagh was the star boomerang thrower and high jumper and also took part in events including backwards sprinting.

Also known by the traditional name Unaarrimin, Mullagh was a Jardwadjali man from western Victoria who learned to play cricket working on a nearby farm. Locals in the Wimmera town of Harrow named an oval after him and placed a plaque to mark the spot where in 1878 he launched a cricket ball out of the oval, across the street and into a paddock — the memorial is 151 yards (138m) from the crease.

In 2020 he belatedly became the first Indigenous player inducted into the Australian Cricket Hall of Fame, and the best player in the MCG Boxing Day Test is now awarded the Mullagh Medal.

CHARLIE SAMUELS

Samuels was Australia’s greatest runner in his day and considered by some to be the fastest man in the world. Born at Jimbaugh Station in Southern Queensland in 1864, he grew up with the local Bunyinni people and worked as a stockman, entering local running events at Toowoomba and later Sydney, where he left opponents in his dust.

Running experienced a boom in the 1880s and the best athletes from England and America competed in races on the grounds of the Sir Joseph Banks Hotel. In 1886 Samuels ran 136 yards (124.5m) in 13.2 seconds, the fastest time recorded in Australian professional athletics.

He is credited with the times of 300 yards (274.5m) in 30 seconds flat and 100 yards (91.5m) in 9.1 seconds, although he may have been aided by race promoters’ tendency to shorten the track.

According to sporting newspaper The Referee, Samuels trained on “a box of cigars, pipe and tobacco, and plenty of sherry”, adding “... it might be a more pleasant reflection to Australians, perhaps, if a white man...could be quoted as champion; but ... Samuel has, in a long course of consistent and brilliant running, established his claim, not only to be the Australian champion, but also to have been one of the best exponents of sprint running the world has ever seen.”

Sadly, the last 11 years of his life were unhappy ones, shunted between Aboriginal reserves before dying of tuberculosis in 1912.

ROBERT KINNEAR AND LYNCH COOPER

Early Indigenous runners had to fight appalling discrimination. The Queensland Amateur Athletics Association tried to ban all Aboriginal athletes from competition on the grounds that they either “lacked moral character” or “had insufficient intelligence”.

But some, like Samuels, defied these obstacles to become champions. Kinnear became the first Indigenous runner to claim the Stawell Gift in 1883, winning off 14 yards in 12.5 seconds; the Melbourne Sportsman described him as “literally a dark horse from the mission station near Dimboola”.

After Kinnear’s death in 1935 the Weekly Times recalled his famous victory: “So great was his delight at winning the famous handicap, and so easy was his victory, that he breasted the tape with his hands above his head.” It also reported that Kinnear was “the last of the Yurra Yurra tribe”.

Kinnear is one of four Indigenous runners to win the Gift (Joshua Ross became the fourth when he won the race twice, in 2003 and 2005). In 1928 Yorta Yorta man Lynch Cooper not only took out Australia’s richest footrace but reportedly collected another 3000 pounds after selling his fishing boat and placing the proceeds on himself at odds of 60-1.

The following year, Lynch won enough points from races in Melbourne to be declared the world’s professional sprint champion for 1929, which is believed to make him the first Indigenous world champion in any sport. The son of prominent Aboriginal rights campaigner William Cooper, Lynch also spoke out on behalf of his people.

Meanwhile, another Indigenous runner Bobby McDonald is credited with being the first athlete anywhere in the world to use a crouch start, in a race in 1887. “I first got the idea of the sitting style of start to dodge the strong winds which made me feel cold and miserable while waiting for the starter to send us away,” McDonald told The Referee. “One day while sitting down, almost, the starter sent us away and I found that I could get off the mark much quicker than ever I could standing.”

EDDIE GILBERT

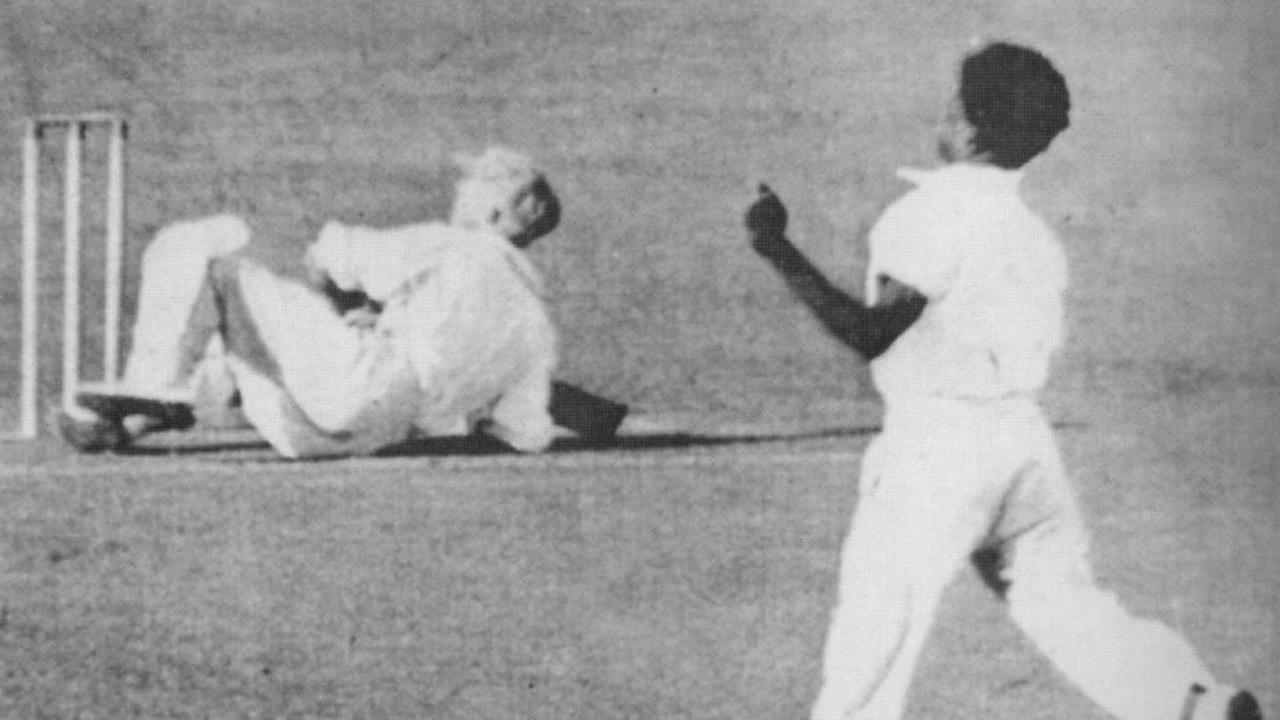

Unfortunately there was no speed gun in 1931 but Sir Donald Bradman would later describe the spell he faced on the opening day of that Sheffield Shield season as the fastest he ever encountered.

Returning to Australia a national hero after blasting an incredible volume of runs against England and the West Indies — including a world record 334 — The Don took his block against young Queensland quick Eddie Gilbert after NSW opener Wendell Bill was out caught behind with the first ball of the innings.

Bradman defended his first ball but the second clipped his cap, sending him sprawling on his backside, and the fifth knocked his bat out of his hands — Gilbert is the only bowler to achieve that feat in Bradman’s long career. Next ball he was caught behind for a duck.

Bradman later said Gilbert’s deliveries were “faster than anything seen from (England fast bowler) Harold Larwood or anyone else” and famed radio broadcaster Alan McGilvray said he had “absolutely no doubt” that Gilbert was “the fastest bowler I ever saw”.

Sadly, Gilbert never represented his country, restricted by the Aborigines Protection Act, which required him to have written permission to travel from his Aboriginal settlement each time he played for Queensland. Even more tragically, he spent the final years of his life at the Wolston Park mental hospital in Brisbane battling alcohol addiction and dementia. He died in 1978. In 2008, a statue of one of Australia’s great Indigenous athletes was unveiled at Brisbane’s Allan Border Field.

JOHN KINSELA

“Uncle John” Kinsela was Australia’s first Indigenous Olympic wrestler and first Aboriginal dual Olympian, and something of a Forrest Gump of Australian sport, intersecting with major historical events throughout his life.

Born in Sydney’s Surry Hills in 1949 to a Wiradjuri father and a Jawoyn mother, he left school at age 14 to work at a sock factory and discovered the sport of wrestling when his boxing trainer didn’t show up and the wrestling coach invited him to try his luck on the mat.

Kinsela enjoyed a meteoric rise, winning the Australian championship and selection for the 1968 Olympic team at just 18. He lost both his bouts in Mexico but was on hand to witness Australian 200m silver medallist and friend Peter Norman stand in solidarity with Black American runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their famous black power salute (a gesture for which Norman was ostracised by the Australian Olympic movement).

Kinsela was sent to Vietnam after his birthday was pulled out of the national lottery and fought in 1970-71 then managed to qualify for the 1972 Munich Games in just five months. He finished seventh in the 52kg division then witnessed the worst episode in Olympic history, when the Games were postponed following a terrorist attack in the athletes village; “I was in Vietnam the year before the Olympics, and I knew the sound of the AK-47s, I just shook my head and thought, ‘Not here’,” he later told interviewer Stan Grant.

Kinsela retired after the Games, was talked out of it and qualified for the 1976 Olympics but never travelled to Montreal, retiring for a second and final time. But he wasn’t done. Kinsela fulfilled a lifelong dream by joining the SAS and spending six years as a commando before returning home to work with his Indigenous community and up and coming wrestlers. In 2017 he was awarded the Order of Australia medal and he died last year, aged 70.

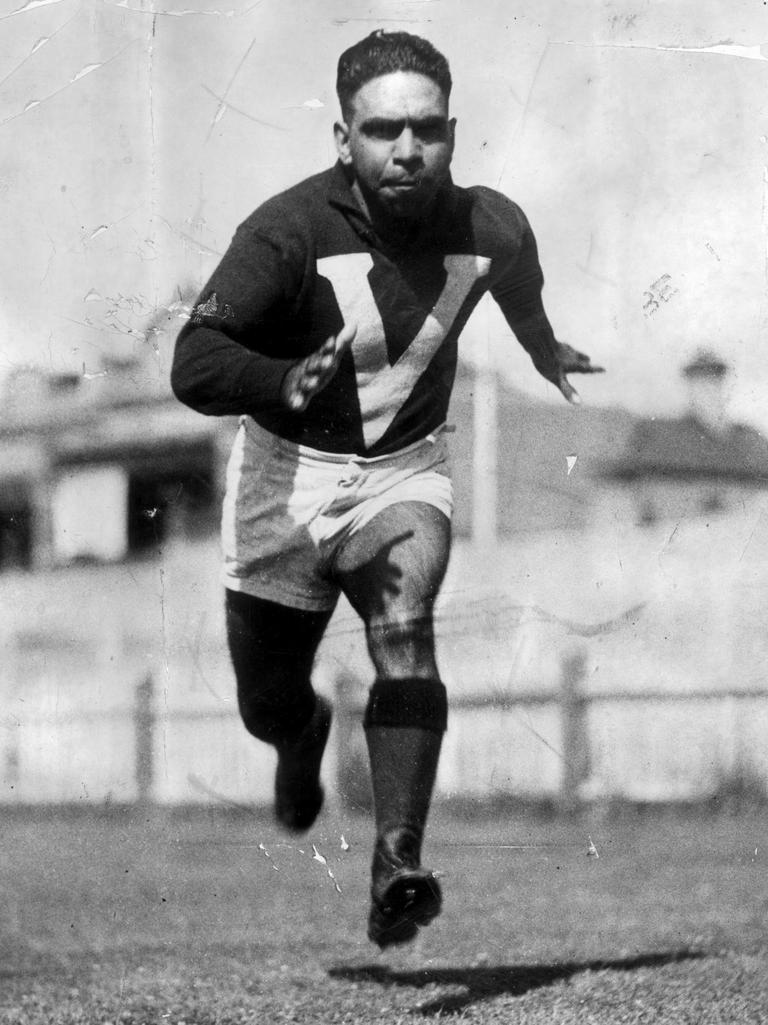

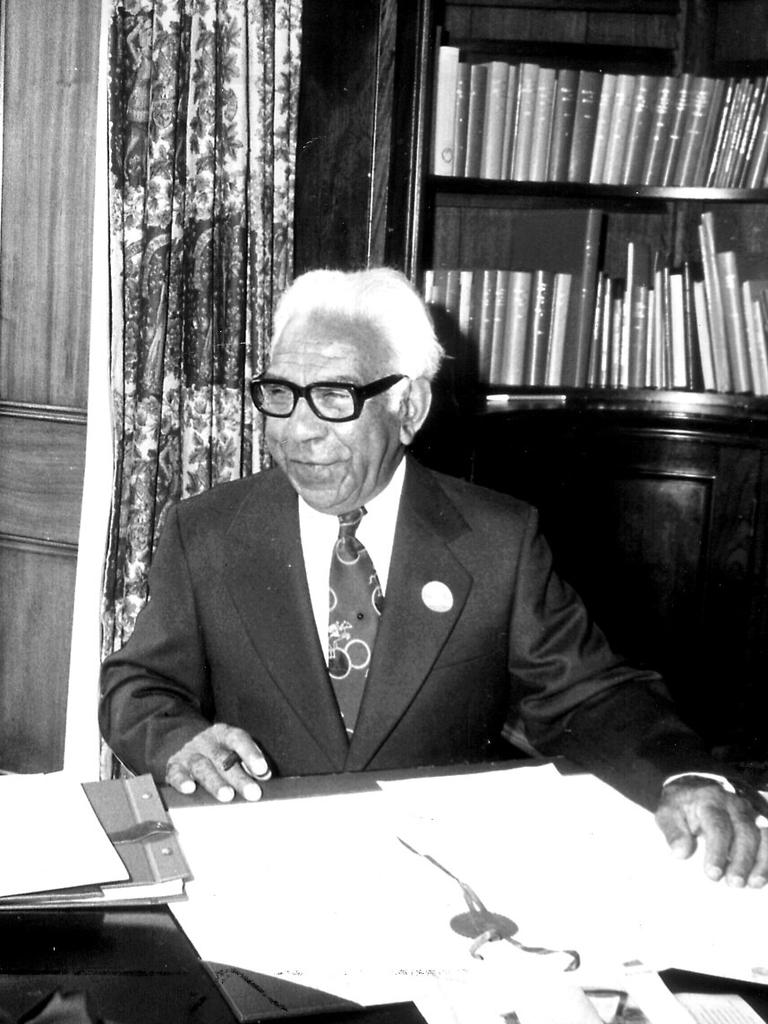

SIR DOUG NICHOLLS

He lends his name to the AFL’s Indigenous Round, but how much do we know about this great football trailblazer?

Nicholls played 55 games for Fitzroy in the 1930s and became the first Indigenous player to represent Victoria after growing up on the Cummeragunja Aboriginal Reserve on the New South Wales bank of the Murray River, on the land of the Yorta Yorta people.

After being forced to leave school he worked on sheep farms then moved to Melbourne to make the most of his outstanding athletic talents. He was one of the shortest players in the game at 157cm but dazzled with his speed and skills despite being singled out by spectators and players, including his own teammates, for his skin colour.

He was forced to retire due to a knee injury but his amazing career was just getting started. Nicholls became a pastor and an advocate for Aboriginal rights, culminating in the 1967 referendum that recognised Aboriginal people as Australian citizens.

He became Australia’s first non-white State Governor when he was appointed to the top post in South Australia in 1977. He served only 150 days, retiring due to ill health, but managed to get knighted twice. After his death in 1988 he received a state funeral.

Grandson Gary later recalled: “What grandfather said is to get a tune out of the piano, you can play the black notes, and you can play the white notes. But to get harmony you’ve got to play both. And that was reference to reconciliation, for probably the first time.”

HARLEY WINDSOR

There aren’t a whole lot of non-white athletes from any country at the Winter Olympics, and Australia didn’t have an Indigenous representative until 2018.

Windsor grew up in Rooty Hill and not the red dust of the outback, but his journey is no less remarkable. He got into figure skating “by accident” — “I took a wrong turn with my mum and I found Blacktown Ice Rink and asked if I could go in and everything kind of took off from there.”

A descendant of the Weilwyn, Gamilaraay and Ngarrable peoples, Windsor’s enjoyment of traditional dances as a child quickly translated to the new sport; he was state champion within a year and competed in his first international competition at age 12.

In 2015 he was paired with Russian-born Ekaterina Alexandrovskaya, who didn’t speak English, but the unlikely pair became junior world champions in 2017 and the next year they made Olympic history in Pyongyang, finishing 18th in the pairs short program.

“The attention has been amazing and I just hope I’ll be a bit of a role model now,” Windsor said.” Hopefully more Indigenous kids get into winter sports.”

Sadly, this story has a tragic postscript, with Alexandrovskaya dying in Moscow last year at age 20 in heartbreaking circumstances.

BRAD HARDMAN

Hardman was a promising junior rugby league player when his life changed on an outer Sydney street at the age of 15.

More Coverage

He was in the back seat of a Holden Calais which slammed into a power pole at 200km/h. “The car split in half,” he told the Courier Mail in May this year. “I went with one half of the car and my left leg went with the other one. I spent months in hospital and it took me years to get over the shock.”

Hardman had to learn to walk with a prosthetic limb and thought his sporting dreams were over until he attended a day for amputee golfers at Cronulla. He went on to win the Australian Open Amputees Championship, shooting 86 off a 22-handicap five years after taking up the sport, and also finishing third in a tournament in Japan.

He is now focusing on boxing — campaigning for the sport to be included in the Paralympics — in between mentoring Indigenous youth.

Originally published as Nine amazing Indigenous Aussie sports stars you probably haven’t heard of (but should)