Indigenous Sport Month: Michael O’Loughlin’s special Q&A with Mark Robinson

Michael O’Loughlin felt ‘sick’ and ‘angry’ at the treatment of his people. He tells Mark Robinson of his cultural pride but fears for the future.

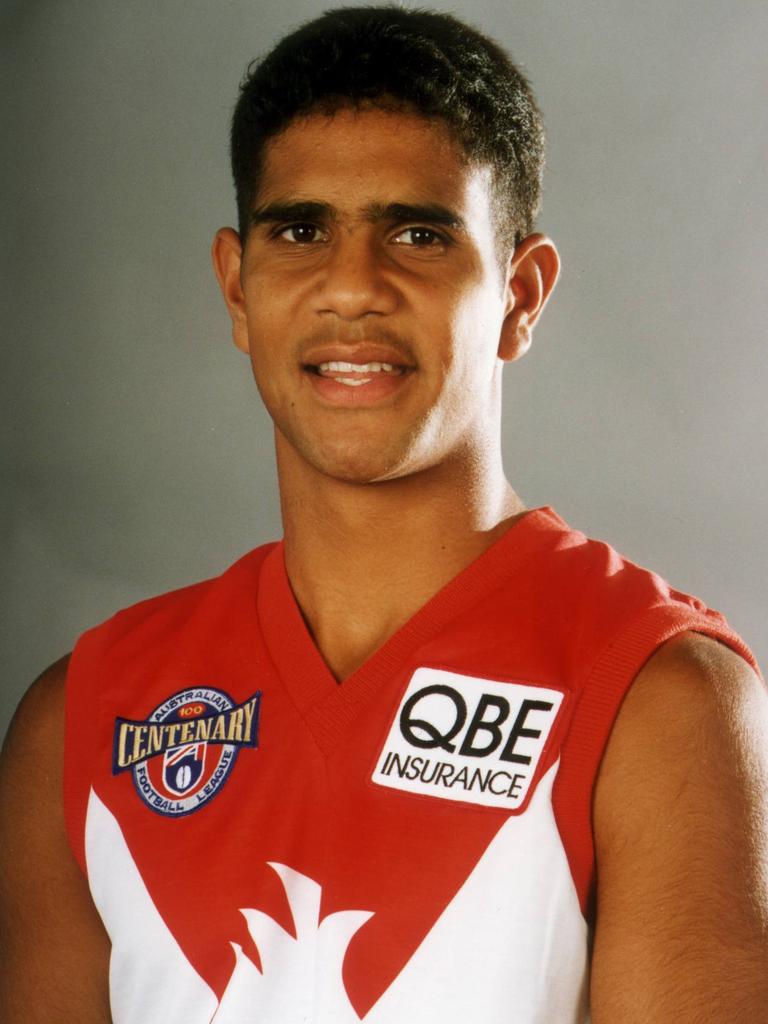

Michael O’Loughlin was one of the finest Indigenous players every to pull on the boots.

As part of Indigenous Sport Month, the Sydney legend has opened up on life, footy and his connection to his culture.

He spoke with Mark Robinson in a special Q&A.

MARK ROBINSON: Where are you driving to on this very crisp Wednesday morning?

MICHAEL O’LOUGHLIN: Driving to the new international airport. They’ve got a reconciliation day there and I chair their reconciliation committee. We’ve got to get Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and people employed at the (Sydney) airport. Out west of Sydney is the biggest population of Indigenous people in the country, so they can’t afford to miss out. This will be a good day.

MR: What is your full-time job?

MO: I own ARA Indigenous Services which is one of the biggest Indigenous businesses in the country. At one stage, I was leaning towards being an AFL coach, I had offers, and I ran the Indigenous programs at the AFL and also took over Jason McCartney’s role at the (Australian) Institute of Sport.

Stream selected Fox Footy shows on Kayo Freebies completely free this June including AFL 360, On The Couch, Bounce & more. No Credit Card. No-brainer. Register Free Now >

MR: So, what roles do you have in football?

MO: I’m on the board of the Swans, appointed three months ago. I love the place. I sit on a lot of other boards but this one is dear and near to my heart.

MR: Back in 2012, you were on Who Do You Think You Are? Who is your mob, Mick?

MO: Mine is Ngarrindjeri, Narungga and Kaurna. Obviously I’m from South Australia and I’m pretty much related to everyone down there.

MR: Because you were totally dedicated to working hard to reach your AFL dream, is it fair to say that as life played out, you became even more connected to your past?

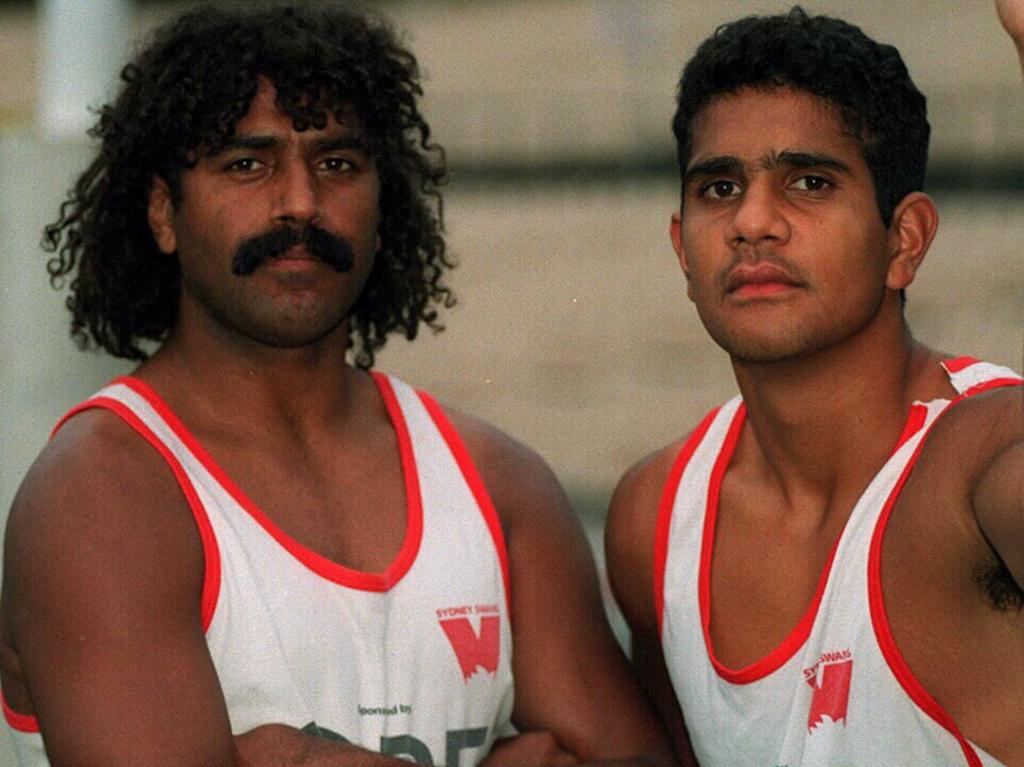

MO: I grew up with really strong leaders and role models and that was drummed into me early. I knew exactly who I was and where I was from. As I got into football, every time I played AFL footy I knew the community was watching and that was an extra spur for me, to play well and make them proud. Our community in South Australia … like, Gav Wanganeen was one of my favourite players, we both played at the same footy club. He was probably the first guy who I thought, “Wow, he’s from our community, he’s a Ngarrindjeri man as well”. Gav was the absolute superstar for us in terms of role models. He played for the mighty Salisbury North Hawks which has got a big Indigenous population north of Adelaide.

MR: When did you first learn about European settlement and what happened to your ancestors? The murders, the rapes, the displacement?

MO: It was told to me as a young kid, but I didn’t understand it. It’s not until you actually get to the NAIDOC marches and you would ask the question: “Mum, why are we marching?” And she would explain why. As a kid, all you wanted to do was have a kick of the footy and hang out with your mates, but you gradually learned about history and what our people have gone through. And, I guess, the atrocious conditions our people lived with. Our elders, and your Nana and Pop, they’d talk about the tough times they had growing up and their role was to make sure the next generations were better looked after. These stories are important and I’m at that stage now where I’m talking to my kids about them.

MR: If you can remember, how did you feel the first time you saw old photographs of your people in neck chains?

MO: Sick. You feel sick, you feel angry. You think, how could this happen? We share stories really well. We talk about the stolen generation, and you talk about the horrible things that happened to the younger people through that period and what my people went through. It makes you angry. It’s like being called an Abbo on the field and as a kid all I wanted to was fight. And it wasn’t until my mother and grandmother pulled me aside and told me to cut that out. They told me, this wasn’t the first time it was going to happen and it won’t be the last time, and you won’t be able to fight everyone. What we had to do was kill them on the field, get possessions and kick goals. It was explained to me this was the way I could fight without trying to punch people every two minutes. Then Nana would tell you how she grew up and went to school and it was just horrible. And your grandfather would tell you stories, and your uncles. Racism in my view will never stop, but what we’re getting better at is recognising it and calling it out. I say this wherever I go, that my culture is your culture, and we want Australian people to love this culture. We need respect, we need things to be recognised and acknowledged, that’s what we’ve ever asked for.

MR: The fact is your grandparents and their parents weren’t treated as human beings.

MO: Correct. This is where sport has been an unbelievable vehicle, and we’re not just talking about footy. Sport teaches our kids about healthy lifestyles, discipline, respect and education. But when you go to the footy and someone is booing your mate or calling someone a monkey or an ape, it’s bloody disheartening and disgusting. It’s what’s acceptable at home and that’s the reason why these people feel they can say those things. You know, I Iove and believe in people and give them the benefit of the doubt, but until we right some wrongs, we’ve got a long way to go.

MR: I liken our history to slavery, and similar to how the Americans stole people from Africa. There are documentaries about that and movies about that. Can I ask how you felt when you watched Django Unchained for example?

MO: Absolutely it made me angry. There’s a whole raft of emotions when you watch documentaries and/or movies. Do yourself a favour and watch Thirteen on Netflix. It talks about the 13th amendment and how slavery came about and chain gangs. Because slavery was abolished, the way around that was we could arrest these people and put them in chain gangs and make them work. Education is what we teach now, upskilling our kids about what their rights are and what rights they do have. And sport has played a huge role in that.

MR: How is the battle going, Mick?

MO: There’s the trauma around the stolen generation, and you just talked about what happened in America, and I read somewhere a politician said there was no slavery in Australia. We’ve all seen the photos of our people in chains. The stolen generation … they were taken away from their communities, and from their parents and loved ones, and forced into becoming housekeepers. What do you call that? They weren’t paid for it. It’s slavery. We’ve survived here for thousands and thousands of years and European colonisation has only been here for a couple of hundred years. We were doing pretty well before anybody came here. What I teach my kids and other young people is that acknowledging our past is important to our people because the trauma they’ve been through is just horrible and it leads to other things, like suicide, mental health, alcohol, drugs because people don’t know how to deal with these things. And if you look at the front page of newspapers you only read about the mad and sad of Aboriginal people. You never read the great things unless we’re winning premierships and Brownlows or winning gold medals.

MR: Were you racially abused on the field in your career?

MO: No, not from a player. You hear a slight remark from the crowd. But as a junior, absolutely. Obviously, there is clearly credible evidence of what has happened at AFL level and we need to call that out. That conversation has to start at homes of non-Indigenous families. A child will then ask his mother or father: “Why does Adam Goodes or Michael Long get upset about being called a monkey, I didn’t know a monkey is a bad thing to call a black person.” That word monkey or ape, it’s names being used for centuries to degrade us and to keep us at a certain level and it’s a knife through the heart. We don’t want to deal with that s**t anymore and we’ve got the voices and power to say, we don’t want that, please stop. The conversation at home is really important.

MR: What’s your emotion as you talk right now?

MO: I have a couple of them. And the one I have most is the sense of pride of who I am and what I stand for, and for my people. I know who I am and that fills me with pride and we want to pass that on to the younger generation. Reconciliation is not Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s problems. I don’t need to learn about reconciliation anymore, the rest of Australia and non-Indigenous people need to pick up the slack. It’s about how they can help. Everyone has benefited from this incredible place we call Australia, except Aboriginal people.

MR: When did it dawn on you that you were a leader.

MO: Being the eldest of six kids and with a single mum. We have an attitude that it’s not mine it’s ours and how we can help each other. That’s what we do, we help each other.

MR: How much did the power of your leadership grow when you began playing with the Swans?

MO: I was like that as a kid anyway. A lot of my mates growing up were white, so it was about teaching them that our cultures was incredible. When I came to Sydney as a 17-year-old, you sort of sit in the corner and shut your mouth. But what footy then enabled me to do, and others, is have conversations with my teammates who might not have necessarily had a conversation with another Aboriginal person.

MR: The first conversation I had with an Aboriginal person was with Michael Long.

MO: There you go, how old were you?

MR: About 26 or 27.

MO: There’s my example right there and how much better do you feel about your relationship with Longy?

MR: He’s a special bloke. And I would not have met him other than through footy

MO: The first Aboriginal person I saw do really well for themselves was an uncle of mine called Wilbur Wilson. He played 170 games for Central Districts. We’re very tight and he was a great example of playing footy and looking after your family and your community.

MR: You were proud of your football career, but are you prouder of what you and Adam Goodes have achieved with the GO Foundation?

MO: Our legacy, and Adam and I see eye-to-eye on this, will be the GO Foundation and not football. Football was unbelievable and for a period of time we did it really well. You only get one crack at life and you do make mistakes along the journey, but ultimately you’ve got to help other people. That’s why the GO Foundation will be our legacy.

MR: Describe footy Mick.

MO: Fun, I love it. My son is in the Swans Academy and I love watching him. He was watching an old replay on Fox Footy and yelled out from the other room, “Dad, you’re on telly’’. So, I walked in there proud as punch and asked where I was. He said, “On the bench”. Apparently, I missed a tackle and I said Rodney Eade probably dragged me (laughing). My son hasn’t missed a Swans game. I love him for loving my club which helped me to become a man. I left my tribe in Adelaide and found a new one in Sydney. Footy’s been a game changer. It’s not perfect, but I love it and my son loves it and my people love it. It’s changed lives and it’s helped change policies. But we’ve still got a long way to go.