TasWeekend: How a beer label led to Leigh Carmichael’s brilliant new career

AFTER years of insecurity, outgoing Mona creative director and Dark Mofo mastermind Leigh Carmichael is finally feeling confident as he faces his next big challenge.

IF Mona has helped cure Tasmania of its inferiority complex, the same could be said of its effect on the museum’s creative director Leigh Carmichael. It has taken a while for the art world to take this wunderkind from the Huon Valley seriously and it has taken Carmichael a while to stop feeling the need to apologise for choosing to stay put in his treasured island state.

His appointment this month to the board of the Australia Council for the Arts signals how important Mona has become to Australia’s cultural identity. For Carmichael, it is the culmination of a 10-year journey from angst-ridden, under-paid graphic designer on the verge of an early mid-life crisis to an esteemed cultural authority.

“For me, it’s huge,” Carmichael says of the honour of being appointed by Federal Arts Minister Mitch Fifield to the board of the Government’s arts funding body.

The 41-year-old, who is the mastermind behind Mona’s annual Dark Mofo winter festival, joins other new appointees including former Rio Tinto chief Sam Walsh and arts advisor Kate Fielding on the 12-person board, which oversees the way the council distributes grants and other funding.

How much sway he can have from within the notoriously bureaucratic beast of the Australia Council remains to be seen, but Carmichael intends to use his three-year term to challenge his peers to look outside their comfort zones.

As he points out, neither Mona nor most of its side-projects would have won Arts Council funding and yet, despite their often challenging content, they have been widely embraced by the Australian public.

Carmichael also intends to fly the flag for small arts organisations, which are struggling for survival amid tightening federal budget constraints.

“Having worked with organisations like the Salamanca Arts Centre, IHOS Opera and Ballet Lab, I’ve seen the amount of energy that goes into continually writing funding applications,” Carmichael says.

“When it’s public money, I understand it needs to be accountable.

But that’s always concerned me, the amount of effort that these often tiny organisations have to go through and that horrible space afterwards where their lives are on hold as they wait months and months.”

Carmichael is yet to decide if he will show up to his first board meeting with a few four-packs of Moo Brew beer, the labels of which were originally designed as a bit of an up-yours to the Australia Council.

The artwork on the labels was based on paintings by Melbourne artist John Kelly, who was outraged by what he saw as the Australia Council’s attempts to commodify and brand art.

Kelly took the sun and kangaroo from the Australia Council’s logo, defying the organisation’s orders not to tamper with the motif, turned them into a series of paintings and, in an ultimate act of commercialisation, sold them to Mona for its beer labels.

“His work was objecting to the concept of branding the arts, because conformity and homogeneity are at odds with the diverse and rebellious heritage of good artistic practice,” Carmichael says.

“So when John ‘sold out’ to [Mona founder and owner] David Walsh, he knew exactly what he was doing, and the project went full circle.”

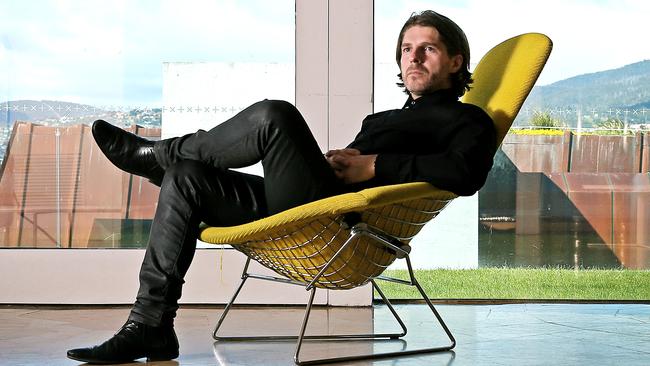

We are in the lounge room of the Mt Nelson home Carmichael shares with wife Angela, a former state netballer, and their three kids, Jenna, 17, Locke, 13, and Zak, 8. Carmichael says he often sits in the room for hours on end, looking out over the wide deck to kunanyi/Mt Wellington, pondering the latest challenge arising from what he calls the “chaotic” workplace that is Mona.

It is a 1980s brick house, but not a typical suburban home. It has a bold architectural roofline and large expanses of glass.

Inside, the feel is minimally stylish, with tan leather couches, fireplace, sleek black stereo system and some of Kelly’s artwork on the walls.

“I’m not exaggerating,” Carmichael says as he describes the insecurity and self-doubt he suffered as a teenager and, later, as a directionless freelance graphic designer in Hobart, when all his peers had left for bright lights and opportunities elsewhere.

He grew up in the tiny township of Glen Huon, loved the local primary school and thrived at high school at nearby Huonville, but did not cope well with the transition to Hobart College for years 11 and 12.

“I didn’t cope with the lack of uniform because I suddenly had to think about what I was going to wear every day and we didn’t have the money for new clothes. The daily bus commute was also an ordeal. I also had this weird thing, something about coming from the Huon. I remember thinking, ‘Everybody else is so much smarter than me’, and, ‘What did I miss?’.”

For 10 years after college and the University of Tasmania art school, Carmichael worked in Hobart as a graphic designer.

“I deeply love Tasmania and never wanted to leave,” he says. “Most of my friends who I went through art school with did leave because there were far more opportunities. So I was working in Tassie and I worked really hard, but we were basically living off Angela’s wage.

“We had kids [when we were] young. Then at 30, as a freelancer, I had a fairly serious mid-life crisis, albeit an early one, thinking, ‘If I don’t achieve something soon, this is going to pass me by’.”

Carmichael scored the contract to design the Moo Brew labels and everything changed. Although he reckons the award-winning label project was handed to him “on a plate”, Carmichael’s design work impressed Walsh and, in 2006, he was offered a full-time job on the design team for the museum the multi-millionaire gambler was planning.

Walsh says that after several frustrating meetings with design firms who wanted to tell him what sort of beer he should be selling, Carmichael came along, drank one of the beers and said “this is good beer, I can sell this”.

“That was a completely satisfying approach compared with what I saw as normal marketing practice,” Walsh tells TasWeekend.

He says Carmichael also oversaw the iconoclastic branding of Mona, which is based on the premise that the opinions of Walsh and his curators are no more valid than anyone else’s.

“Sometimes I think Mona is the wonky training wheels for the bicycle that real museums are,” Walsh says.

“We start people on a journey of exploration of art and philosophy. Leigh pushed me in the direction of having really cohesive consistent branding for Mona.”

I ask Walsh if he feels Carmichael has finally shrugged off the insecurity he was plagued with earlier in his career.

“No. I think he’s still pretty insecure,” Walsh says. “He wears his heart on his sleeve.”

Mona opened in early 2011, with Carmichael the museum’s creative director, and the first Dark Mofo was held in 2013. As well as the now-famous nude solstice swim at Sandy Bay, the first festival featured Spectra, a 15km-high light installation beaming above Hobart.

So overwhelmingly positive was the public response there were widespread calls to make Spectra a permanent exhibit.

“The satisfaction you get from running a festival that is so supported by the community, and 20,000 or 30,000 people turn out on some nights and just kids walking around looking up at Spectra, that’s the thing I’m most proud of,” Carmichael says.

“I hate it for most of the year because it’s just a nightmare with the expectations, but I just really, really love it.”

Not only has Mona made Hobart the hottest destination in Australia, every arts organisation in the country seems to want to hear what Carmichael has to say.

“It’s been fascinating, this Mona journey,” he says. “When I first started [working for Walsh], I’d go to these architect meetings in Melbourne and meetings with the interior design team and I would sit there and feel invisible. I’d say something and feel invisible.

“You grow up with all the jokes about us being a backwater and two-headed Tasmanian and inbred, and you laugh it off and you know it’s not actually true, but at the same time it does sit within your psyche and identity.

“Now Hobart has the most important contemporary cultural institution in the country. Major artists are prepared to come and put shows in Mona, who aren’t prepared to put them in the NGV and other major galleries.”

No longer invisible, Carmichael is asked to speak around the country about his work at Mona and Dark Mofo. He has declined requests to extend the festival interstate.

“Doors open and people are interested. But I’m the same person,” he says.

Festival-goers rushed to hospital, naked swimmers threatened with arrest, screaming matches with international artists – no wonder Carmichael loses so much sleep ahead of each Dark Mofo.

“I’m very brave in the meetings when I say, ‘Everything will be fine, let’s do it’,” Carmichael says of the weird and wonderful (and sometimes not-so-wonderful) acts and exhibits he signs up for the winter festival, which is based on themes of darkness, grief, death and facing fears.

In 2013, at least seven people were taken to hospital after suffering seizures while viewing an immersive artwork called Zee, which involved strobe lights, thick smoke and thumping music.

The first nude solstice swim was initially cancelled after police said participants would be violating indecency laws, but the State Government intervened to allow it to go ahead.

Last year, Carmichael ended up in a screaming match with German sound engineer Bastiaan Maris when Maris objected to his “fire organ” being shut down for health and safety reasons. The giant pipe organ used vibrations from explosions to make music. And it shot flames into the air.

“That was crazy,” Carmichael says. “We had these ‘crack pipes’ which we’d spent a ridiculous amount of money on and they were way over the sound limit. I didn’t want to be responsible for damaging anyone’s hearing so we shut that down.”

Walsh has spent an estimated $14 million on Mona festivals since 2009, while taxpayers put in $2.1 million for this year’s Dark Mofo festival and the State Government recently announced a five-year $10.5 million funding deal to ensure the winter festival’s future.

Despite complaints about noise (and the odd hospitalisation), the festival is hugely popular with locals and tourists, many of whom embrace the raft of free events and the idea of celebrating the coldest part of the year rather than hibernating.

In an era of nanny state rules and restrictions, festival-goers are amazed they can warm their hands by actual fires, not to mention the giant burning effigy that forms the festival finale. As Sydney commentator James Valentine says, “there is no way this event would happen in Sydney”.

“In Sydney, a symbolic fire would be lit,” Valentine wrote in his review of Dark Mofo. “It would be a mock electric fire powered by a battery charged on solar power.”

Carmichael says that is exactly why more people like Walsh should be investing in the arts.

“The private sector, individuals, philanthropists, can do so many more things than bureaucracies and government departments,” he says.

“They just cannot take the risks that we do. We are free to fail.”

He agrees he is often approached by members of the public who believe the Hobart City Council should outsource the summer Taste festival to Mona.

“If the council were to put out an expression of interest looking for interested parties to produce the Taste externally, we’d definitely look closely into the opportunity,” Carmichael says.

On one hand, you could say he has just been sacked. On the other, you could say Carmichael has just been given another incredible opportunity.

As of Tuesday, he will no longer be Mona’s creative director. In fact, he will no longer be part of the museum’s organisational structure.

Walsh has created a new arm of his business, a sort of creative think-tank, to oversee Dark Mofo, Mona’s redevelopment of the old Odeon theatre and any other new opportunities and collaborations that arise.

“Dark Mofo has just got a bit too big. This year it was a $7 million event,” Carmichael says. “I feel a bit sad to be leaving Mona after 10 years but in many ways I feel like I’ve been let out of a cage.”

He is frank about the toll that working in such a “high-energy, chaotic” workplace has taken on him.

“It’s chaotic partly by design,” he says. “David hasn’t really shown interest in making it any less chaotic because I think chaos, lack of structure, the ability to break rules and to be the rebel, push boundaries, that all happens in that less-structured environment.

“But those loose, chaotic environments are difficult to work in because we’re all competing for David’s attention in terms of trying to get our projects up. We’ve all got ideas, so competition is fierce at times and there are lots of winners and losers, for example, if David chooses one artist over another.”

Carmichael says there have been “growing pains” associated with the rapid expansion of so many varied business elements. “To go from a small team to now, there’s something like 400 staff – that’s enormous,” he says.

“We’ve expanded so quickly, so the growing pains are enormous.

We’re not just a contemporary art museum, we’re a winery and a brewery and a function space and a wedding venue, we run two festivals, we have three or four exhibitions a year.

“I think, after 10 years, David’s realised that’s taken a toll on me, so he’s setting me up with my own entity – kind of like Mona’s creative lab – so I’ve got to build up a new team.”

Carmichael is being replaced as Mona’s creative director by ex- Tasmanian Robbie Brammall, an advertising creative who, according to his online bio, “fled the state in 2001” to work in London, Sydney and Melbourne.

For Carmichael and his small team, which will include at least two other Mona staffers, the most pressing task is to complete Mona’s vision for a large parcel of public land on Hobart’s former railyards site.

At the end of last year, the Macquarie Point Development Corporation hired Carmichael and his Mona colleagues to dream up a public precinct concept for its Macquarie Point master plan.

Carmichael says the vision, to be revealed before Christmas, will not be a rigid plan but a vehicle for community debate.

“We’re going to put some suggestions forward but it’s what comes back that’s going to matter,” he says.

Under the existing master plan, released mid-last year to a lacklustre response, about 40 per cent of the 9.3ha site will be public space. The rest is vaguely earmarked for a hotel, retail, offices and apartments. The MPDC admits it is hoping Mona’s involvement will give the plan some cultural credibility, making the site more appealing to investors and developers.

Carmichael has been instrumental in activating the industrial site while the MPDC’s consultation process drags on, converting a section of it into a fairground of music, art, fire and light called Dark Park during the last two Dark Mofos.

He says Dark Park has proved how essential it is to maintain much of the site as genuine public land.

“We had 100,000 visitors through Dark Park in 10 days this year,” he says. “We need spaces where we can get 20,000 to 30,000 people [at a time]. We don’t even have a space at the moment for Carols by Candlelight. We have to split it over two nights, or you go outside the city, down to Sandy Bay. Public space really needs to be in the heart of the city, like Federation Square or, in Sydney, the Botanical Gardens and Circular Quay.”

Having recently returned from the eco-tourism Eden Project in Cornwall, Carmichael says there will be space for an “Eden Hobart” in Mona’s concept for Macquarie Point. “We have a place for it inside our vision and believe it enhances the overall project, but it’s best if Eden reveal their own plans, because it’s not our project,” he says.

When Eden founder Tim Smit came to Hobart in June, he gave little detail about his proposal for Hobart’s waterfront but said it would be like “a James Bond villain’s lair for scientists”.

“Ninety-five per cent sure they aren’t proposing domes,” Carmichael says, referring to the forest-filled biodomes of the Cornwall Eden Project, which were built on a redundant clay quarry.

A few noses were put out of joint by Mona being given a $240,000 contract to work on the public space proposal (much of the work, including the trip to Cornwall, is being funded by Walsh) without the gig being put to tender, but few could deny Mona has the right credentials.

Carmichael hopes the project will include light rail connections between the waterfront and Mona and beyond to the Derwent Valley. He argues Mona has opened Tasmanians’ eyes to what can be achieved on the site.

“I think one of the most profound effects Mona has had on all of Tasmania isn’t the fact that visitors have started to turn up, but that it has given us a sense of purpose and a sense of pride,” he says.

“People do feel some ownership over Mona but ultimately it’s David’s journey, it’s not really owned by the public. But Macquarie Point is.

“Mona has potentially given us the confidence to take this step.

If we can get this right, there’s the potential to have an amazing cultural precinct in the middle of Hobart, with connections right through from ferry terminals to light rail. A gathering place and set of values that could influence our identity and symbolise who we are”.

For more great lifestyle reads, pick up a copy of TasWeekend with your Saturday Mercury.

Originally published as TasWeekend: How a beer label led to Leigh Carmichael’s brilliant new career