Tasman Bridge disaster: 50 years on, we want you to share your memories

It’s been 50 years since one of the state’s biggest disasters rocked the state’s capital. Tell us about your memories of the Tasman Bridge collapse. Free story >>

It was a calamity which quite literally shook the state’s capital.

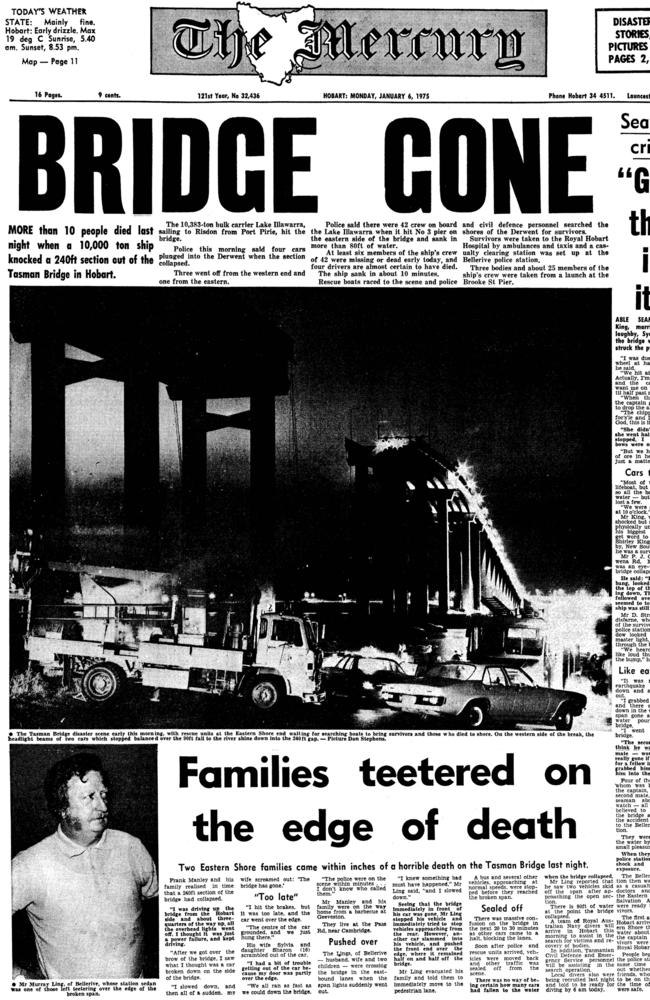

When the bulk ore carrier Lake Illawarra crashed into the Tasman Bridge at 9.27pm on January 5, 1975 it caused a 73m section of the bridge to collapse and in the process divided Hobart.

Twelve people died – five crew on the stricken ship which sank in 10 minutes and seven motorist who plunged into the Derwent when the road gave way.

In just over three weeks the Mercury with mark the 50th anniversary of the Tasman Bridge disaster with a special commemorative edition.

We would like to include the stories of those who lived through the disaster and whose families were directly affected.

If you have a memory sent it to mercuryedletter@themercury.com.au or scan the QR code.

Today former Mercury advertising representative Peter Carey recalls how his family was hit by the twin disasters of Cyclone Tracy on Christmas Eve 1974 and Tasman Bridge collapse which occurred just 12 days later.

How my one bewildered family had to endure two Christmas disasters

As we approach Christmas, it is an apt time to remember the 50th anniversary of two tragic events in our history that attracted not only national but international media attention.

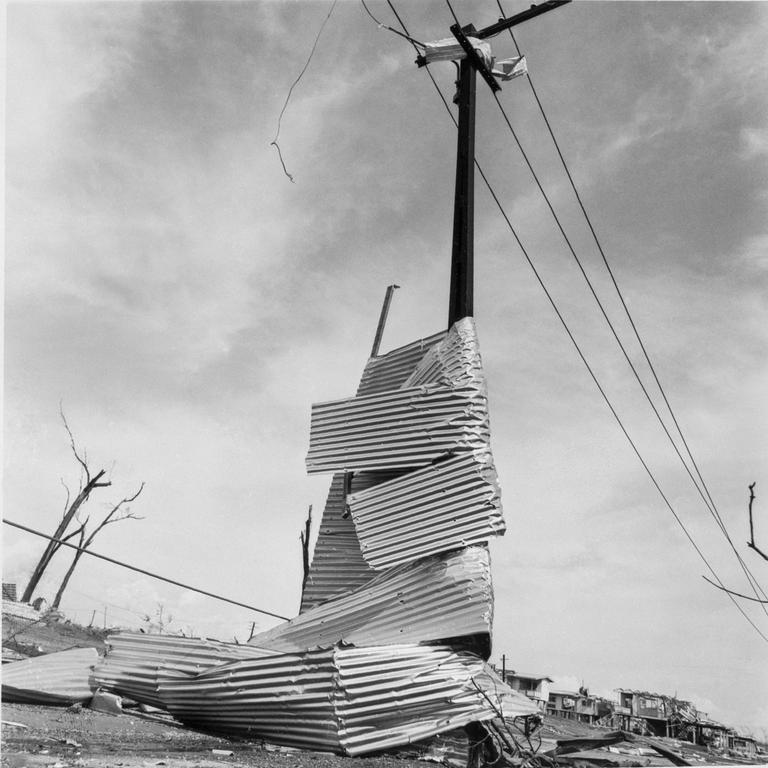

Cyclone Tracy all but wiped-out Darwin on Christmas Eve in 1974. Then, less than two weeks later, the collapse of the Tasman Bridge on January 5, 1975 – after being hit by bulk carrier Lake Illawarra.

Two piers and three spans of the bridge collapsed, claiming 12 lives and leaving Hobart a divided city for more than two and a half years.

For two disasters so close together, at opposite ends of our nation, for my family it represented a double whammy. My brother Bob and his then wife Helen were caught up in the Darwin cyclone, and less than a fortnight later I had travelled over our bridge some five hours before a large section crashed onto the ship and to the bottom of the River Derwent.

I was 15 years old, having just finished year 9, and as the youngest of three was still living with my parents in Glenorchy. My sister Lyn was living in London and my brother Bob was an NCO in the RAAF, based in Darwin where he lived with Helen. On Christmas Eve, they rang us from a public phone to share the usual Christmas good wishes, warning that their time was limited by their need to return to their ground-floor flat in the Darwin suburb of Nightcliff and prepare for what was predicted to be one of the most severe cyclones in Darwin’s history. As they struggled to keep the door closed on the old PMG red phone box, we could actually hear background noise, easily identified as rapidly intensifying wind.

On Christmas morning, it became obvious that it was like no other, as images started to emerge, revealing the true severity of the disaster that resembled a bombed city. The most moving media interview for me epitomised the Australian spirit of thinking of one’s fellow man before oneself; an elderly lady lying in a hospital bed casually uttering the words: “I’ve only lost an eye; some poor people have lost their lives.”

With communications cut, there was no contact. We had no knowledge of Bob and Helen’s fate, so we preferred to take comfort from belief in the old cliche that “no news is good news”. On December 27, we received a phone call from Helen at Laverton airport in Victoria.

She and two other RAAF wives who had been evacuated would be arriving on an RAAF DC-3 at Hobart airport later in the day while Bob stayed on with the rest of the RAAF personnel as part of the relief effort. Later at Hobart airport, the media contingent was obvious, along with several police officers and the Red Cross. While awaiting the arrival of the Dakota, it wasn’t long before a Mercury reporter made himself known to my now late father George, who was very happy to share our story; one that found its way, along with a photo, on to the front page the next day, December 28, and captioned something to the effect of: “Mrs Helen Carey wept as she embraced her father-in-law Mr George Carey of Glenorchy.”

It wasn’t long before strangers, desperate to hear about loved ones, looked up the only Carey listed in the phone book with a Glenorchy address and called, wanting to speak with a very fatigued Helen, who in empathising with them, was happy to share whatever limited information she could.

What Helen shared with us was quite extraordinary, describing how she and Bob spent the night with their backs to the main door to keep it closed and progressively pulling folded linen from a cupboard to prop themselves increasingly higher as flood waters continued to flow in. The most frightening thing for them was hearing the first-floor flat collapsing above them.

Now with Helen chilling out in our company, we weren’t expecting what was to happen on January 5, 1975. After visiting an aunt at her family shack at Primrose Sands, Helen had become quite the centre of attention but still quite comfortable sharing her experience with curious “interrogators”. Later, driving home via the Tasman Bridge, we had no expectation of what was to greet us on the front page of the Mercury on January 6 – that very bridge had collapsed.

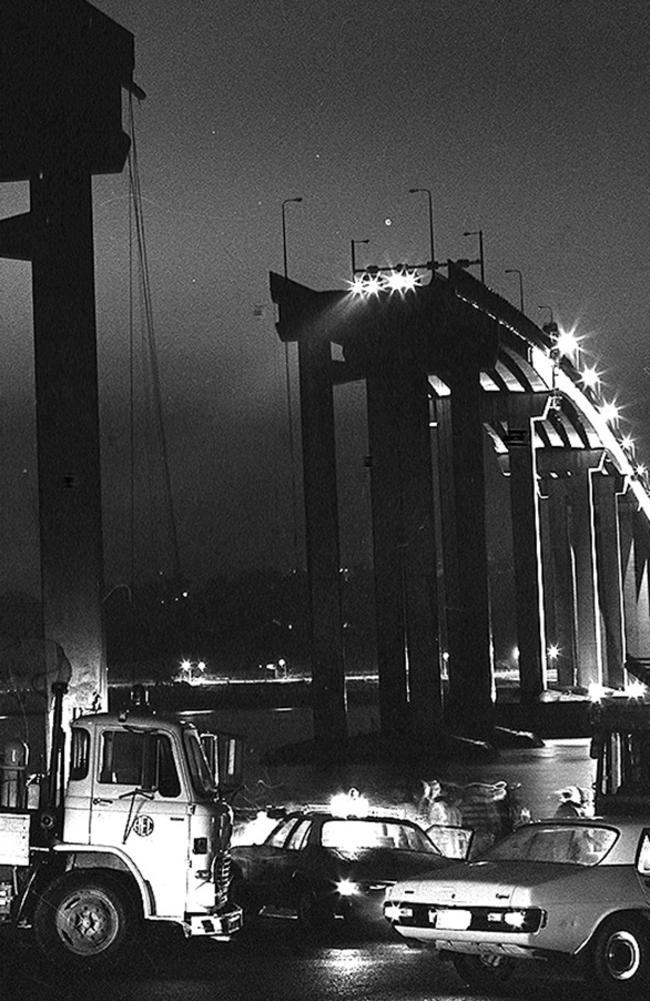

Many would remember the excellent images captured by Mercury photographer, the late Don Stephens, a resident of the Eastern Shore who was first on the scene. Who could forget those images of Murray Ling’s EK Holden and Frank Manley’s HQ Holden Monaro both teetering on the edge of the broken bridge? My wife Diane, albeit some six and a half years before we met, was living at Moonah and still recalls how on that night she heard very distinct thuds – the sounds of large pieces of concrete hitting the ship’s deck.

So that was how the notoriety of that summer manifested itself. If there is any hint of humour to break the stress, it would be when Bob finally arrived by taxi. He explained how he had discovered those many back roads of Hobart’s Eastern Shore, not to mention his newly acquired, self-confessed, irrational fear that something was destined to get him at one end of the nation or the other.

Peter Carey is a former advertising representative at the Mercury.

Originally published as Tasman Bridge disaster: 50 years on, we want you to share your memories