‘Pig butchers’: Inside the AI-powered scam factories dudding Aussies out of millions

Sarah thought she was falling in love with a handsome and well-travelled man named Daniel, but instead fell victim to a sophisticated scam operation.

Sophisticated scam factories staffed by a mammoth 120,000-strong workforce are deploying new technologies to fleece Westerners out of billions of dollars.

And experts say the level of psychological manipulation that victims are subjected to is on par with brainwashing.

An investigation by 60 Minutes has given a glimpse of the dozens of scam factories based in lawless Myanmar in Southeast Asia, controlled by international crime syndicates.

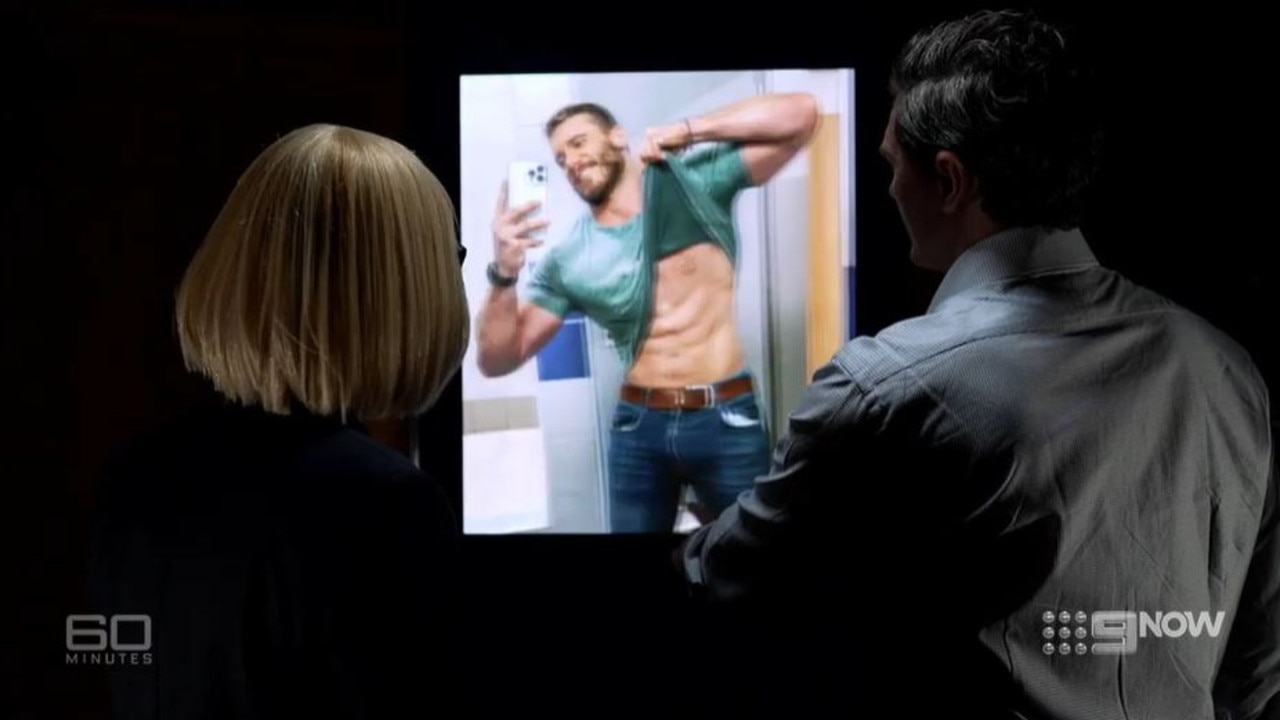

Carefully crafted personas infiltrate legitimate dating apps like Tinder, where they hunt for lonely victims like Australian woman Sarah.

The 45-year-old had been single for decades when she met Daniel, a young intrepid traveller and fitness enthusiast who was kind and attentive.

“I don’t think there [was] anything that wasn’t believable,” Sarah told the Channel 9 current affairs program last night. “His photos looked genuine, there was no reason for me to not believe who I was at wasn’t who he was.”

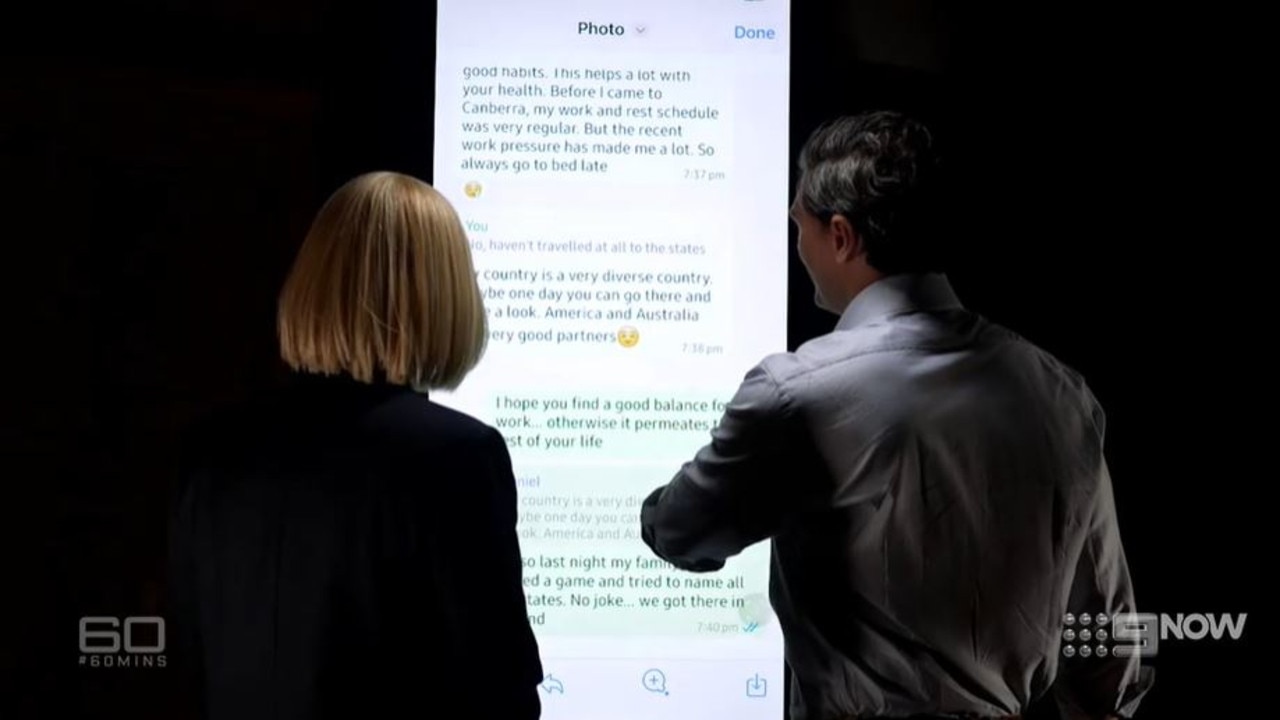

Daniel didn’t exist and Sarah was instead chatting with a scammer, whose tone subtly changed over coming weeks, with the conversation turning to how much money he was making investing in cryptocurrency.

She was convinced to sign up to the legitimate platform CoinSpot, where she spent small amounts of money buying Bitcoin and began to see healthy returns.

Daniel invited her to another platform – this one dodgy – and she invested more and more money, eventually spending a staggering $100,000.

“He was so convincing,” she told 60 Minutes.

Sarah was unable to login to her account one day and contacted the platform, who advised her the site she had been accessing was a spoof.

All of her money was gone.

“It was a horrendous feeling,” she said.

Liam O’Shannessey, executive director of security firm Cyber CX, said scammers are using artificial intelligence technology to convince victims they’re chatting to a real person.

“We used to be able to tell people: ‘Hey, you’ve been chatting with this new friend overseas. It’s probably not that person. If you really believe it’s that person, get on a video call with them.’

“We can’t make that recommendation anymore.”

Mr O’Shannessey demonstrated face-cloning tech that allows scammers to video call their victims – something that wasn’t possible a few years ago.

“We can take these sorts of streams, stream it to a WhatsApp call, stream it to FaceTime calls,” he said. “We can also throw in some voice changing technology as well.”

Another horrifying trend involves the scammers themselves, many of whom are also victims of gangsters that lure them in using similar manipulative tactics.

Australian humanitarian Michelle Moore runs the charity Global Arms and told 60 Minutes the scam factories in Myanmar are largely staffed by people who have been human trafficked.

“I don’t think the average person really understand that there’s a victim trapped on the other side, forced to do this,” Ms Moore said.

“We’re convinced the scammers are bad people, they’re all criminals and they’re complicit. That’s just not the case.”

Many have applied for what they believed were legitimate white collar jobs in Bangkok, the capital of Thailand. Interviews conducted via Zoom with a panel of executives from a fake company offer a convincing front.

When told they’ve been hired, the victims are flown to Bangkok and collected by a driver, who then speeds off several hours into the countryside to the border with Myanmar.

After being smuggled across a river, they are sent to one of dozens of compounds and taught how to scam. Those who refuse are beaten and tortured until they comply.

The technique used is known as ‘pig butchering’, Erin West, a former deputy prosecutor in Santa Clara Country in California who is now a private investigator for scam victims, explained.

“The concept is that [they] fatten up the pig by developing close personal relationships and developing a trust and a warmth,” Ms West said.

Then the scammers butcher their victims and take everything.

Ms West said new technologies and enterprising crime gangs have taken the old school romance scam to horrifying new heights.

The level of psychological manipulation, outlined in detailed playbooks, is akin to brainwashing, she said.

There is big demand for Ms West’s services, with Americans losing a whopping $50 billion to romance scams in 2023.

Here at home, lonely Aussies were fleeced of some $35 million last year, Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Financial Services Stephen Jones said.

“These scams are particularly vicious and exploit the basic human emotion of wanting to connect and find love – it is heart‑wrenching stuff,” Mr Jones said.

“What we’ve put into place is starting to work and we’ve seen Scamwatch reported losses consistently decline since we stood up the National Anti‑Scam Centre – but we urge people to remain vigilant and know how to protect themselves so we can fight this scourge together.

“We are aiming to make Australia the hardest place in the world for these criminals to ply their act and to make it the safest place in the world for consumers.”

Sarah is still picking up the pieces.

While the New South Wales Police scam squad is investigating, they’ve told her the prospect of recovering any of her lost money is low.

“I’m still coming to terms with it,” she said. “It’s still shocking and alarming to think about.”