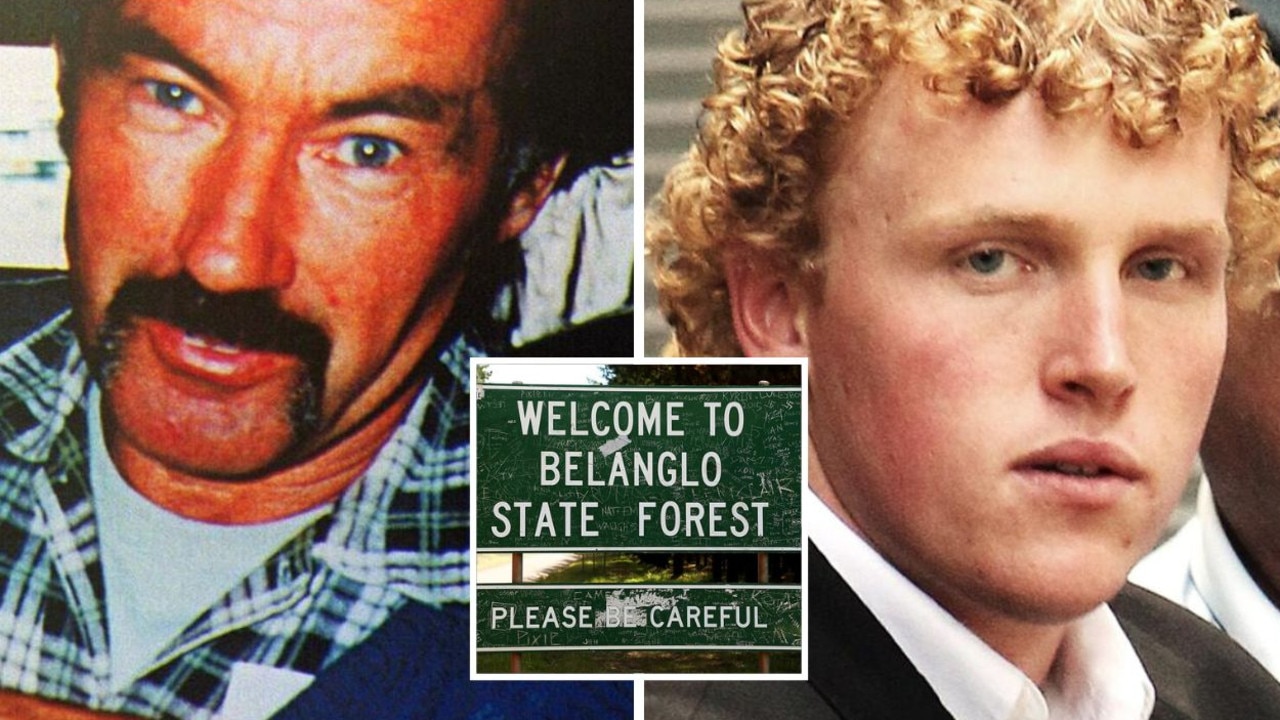

His best mate was murdered by her estranged husband – now he’s got a message for all men

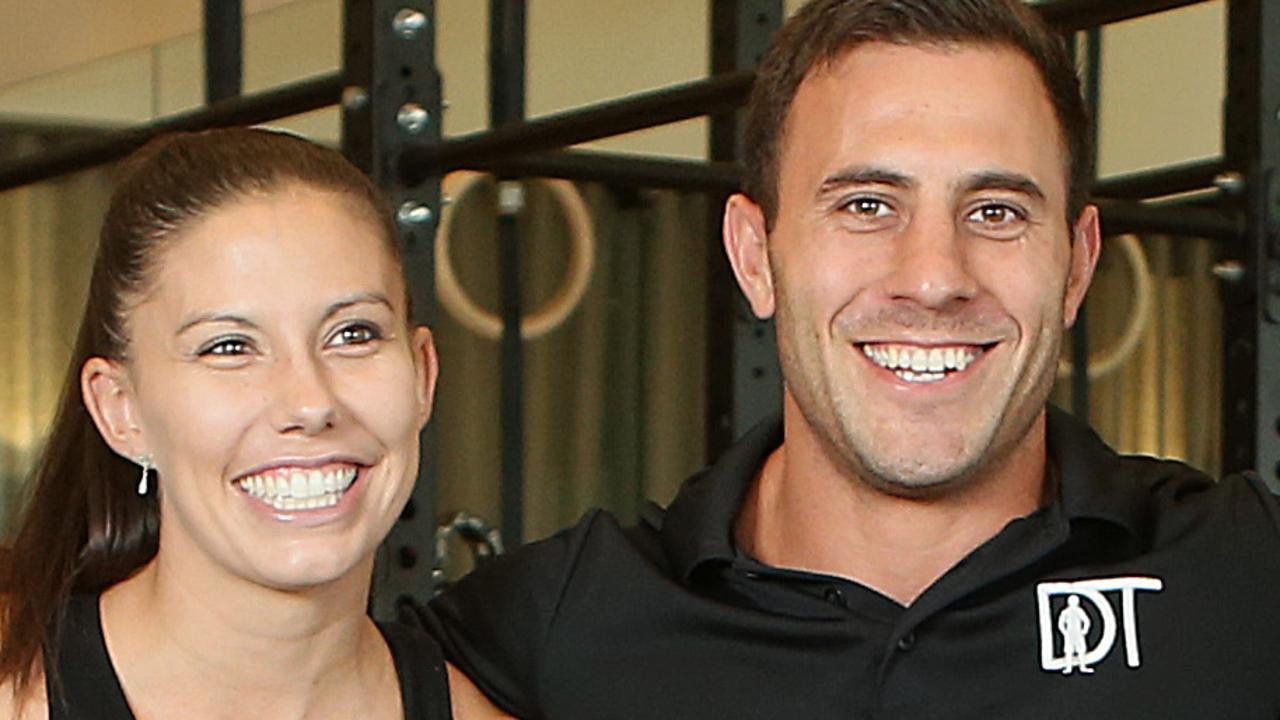

Dave Kramer’s best friend and her three children were murdered by her estranged husband – now he’s got a message for all men.

The horrific murders of Hannah Clarke and her three children rocked Australia, with collective shock quickly turning to angry demands for action.

Their deaths on a sleepy suburban street at the hands of Ms Clarke’s estranged abusive husband would eventually expose a litany of systemic failures and missed warning signs.

And it would prompt her best friend Dave Kramer to up-end his life, finding a new purpose amid unimaginable tragedy and grief.

Mr Kramer, who worked out at the gym owned by Ms Clarke and her then-husband Rowan Baxter and was a close friend of the family, has reflected in the years since of the red flags he didn’t recognise.

Baxter’s domineering behaviour. His sexist and misogynistic comments. A tendency to fly off the handle if his deep insecurities were prodded.

“Before Han passed, I was just like any other guy. If something seems off, you sit back and think, it’s not my problem and it’s none of my business,” Mr Kramer told news.com.au.

“I think you also think it would never happen in your world. You don’t need to worry about anything that serious.

“But it’s a real problem. It’s a real cultural issue. It’s happening all around us, all the time. When it happened to someone I loved, I realised that I should have spoken up in the years before, I should’ve said something.”

But there was no way he could’ve predicted what was to come.

Ms Clarke had just left her parents’ home in the leafy Brisbane suburb of Camp Hill on the morning of February 19, 2020.

The mum, who’d fled her abusive husband to the perceived safety of her mum and dad’s house, was doing the school run, with Aaliyah, six, Laianah, four, and Trey, three, in the car.

Baxter, who had been stalking her for weeks, was laying in wait. As Ms Clarke reversed out onto the street to begin the journey, the 42-year-old emerged.

Ms Clarke screamed for help from a bystander, as Baxter splashed fuel throughout the inside of the car before setting it alight.

In the ultimate final act of cowardice, he died nearby from self-inflicted stab wounds.

The three children died at the scene, while Ms Clarke passed away in hospital later that day.

“Han was my best friend and I loved those three little people,” Mr Kramer said.

Shocking systemic failures

The devastating results of an inquest into the murders highlighted “yet again” how significantly the system had failed, Kate Fitz-Gibbon, director of the Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, and colleagues, wrote in searing analysis for The Conversation.

In June 2022, the findings were released and demonstrated the urgent need for system reform, in a bid to prevent similar arguably avoidable tragedies.

A line in Deputy State Coroner Jane Bentley’s report read: “I find it unlikely that any further actions taken by police officers, service providers, friends or family members could have stopped Baxter from ultimately executing his murderous plans.”

Any temptation to read it as a declaration that Hannah and her children’s deaths were inevitable misses the point, Professor Fitz-Gibbon cautioned.

“This endorses a key message from recent inquiries at state and national levels of the need to increase perpetrator accountability at all points of the system,” she and her colleagues wrote.

“However, we cannot accept as inevitable the status quo that one woman in Australia is killed every nine days by a current or former partner.

“Violence against women is preventable. Baxter’s actions reaffirm the well evidenced fact that men who commit intimate partner femicide rarely do so ‘out of the blue’.”

Since the analysis was published, the frequency of domestic and family violence deaths has increased to one woman losing her life each week, on average.

Warning signs ‘missed or ignored’

Baxter’s horrid history of abuse was well-known by police.

He had been the subject of a domestic violence protection order and had breached those conditions, but was never charged.

Ms Clarke had gone to police on multiple occasions, including over an assault that Baxter was never charged for.

And Baxter’s long history of disturbing coercive control had been reported by one of Ms Clarke’s friends, in an affidavit presented to police before her and the children’s murders.

The coroner concluded that police, as well as other government agencies, had either missed or ignored the warning signs.

In doing so, they had all failed to recognise the “extreme risk” Ms Clarke and her children faced.

In particular, she noted that the failure to charge Baxter following the breach of the domestic violence protection order was a severe missed opportunity.

“The inquest showed Hannah Baxter had been in contact with police and had expressed her concerns to family and friends,” Professor Fitz-Gibbon and colleagues concluded.

“It exposed a system not built to effectively deal with men’s violence against women, or to contextualise every system interaction in a broader pattern in order to reveal the real risk to women and children.”

Among the coroner’s recommendations was a focus on improved policing, better responses from the service system, and an examination of child safety practices and policies.

On that final point, the coroner was particularly scathing.

She found that there had been “no real assessment of risk of harm to the children” by either police of child safety authorities.

The only aspect they examined was whether Ms Clarke was able to properly care for them.

“This finding is critical,” Professor Fitz-Gibbon et al wrote.

“Children frequently remain invisible at different points of the family violence system. Yet in Australia, one child is killed almost every fortnight by a parent.

“While children are typically treated as an extension of their primary carer, the risks children face must be identified and addressed in their own right.”

Shannon Fentiman, who was Attorney-General at the time, expressed hope that the inquest would deliver a lasting legacy of a “much stronger system”.

“It is incredibly distressing … when we hear about these horrific murders and we have to do more to prevent [them from] happening,” Ms Fentiman told radio station 4BC at the time.

“I often say we have to start responding to the red flags before more blue police tape surrounds the family home.”

Turning grief into purpose

In the wake of the deaths, Ms Clarke’s parents Lloyd and Sue launched Small Steps 4 Hannah, to raise awareness of the issue of coercive control and educate children and young people about how to spot it.

Mr Kramer, who went on to study behavioural science at university, was the pioneer of the foundation’s HALT program.

HALT is a groundbreaking initiative that goes into schools to deliver lectures and training workshops about safe and equitable relationships. As well as giving those workshops, Mr Kramer is also a corporate speaker and an ambassador for Small Steps 4 Hannah.

“I talk about Han and the kids often in workshops, so young people can connect with who they were as people, not just what happened to them,” Mr Kramer said.

HALT is about meeting young people where they’re at, rather than giving them a sense of inevitability.

“We use a little bit of our story to help them understand the end of the line, but then we take it right back to where they are,” he said.

“They’re not at that point that Baxter was when he took the lives of Han and the children, they’re not at that point where Han was, trapped in an unsafe relationship.

“They’re at the very, very beginning, having difficulty understanding their emotions, trying to navigate who they are and how they contribute to their community and their social groups, and all that sort of stuff.“

A point of difference for HALT is moving away from the tendency to shame young men, which Mr Kramer said “doesn’t help anyone”.

“Governments are pushing for ‘upstander’ education, which basically means you have to call out your friends or call out other people when you recognise problematic behaviour, which for a young person is an incredibly unsafe space to step into.

“What we’ve recognised in the conversations we’ve had with young people is that it’s much safer to do what everyone else is doing, even if you know it’s wrong. The idea of calling people out is unhelpful. Instead, what we do is we focus on bringing them together.

“How do we engage young people? How do we bring them together to understand what it looks like to actively contribute to the safety of themselves and those around them?”

Stepping into this world – this new life – in the wake of such personal loss has been challenging at times, Mr Kramer admits.

“The personal tax I pay by doing this work is really difficult at times,” he said.

“But the way I see it, tax is beneficial. It supports communities. I’d much rather be out in the community doing this work, doing the best I can to honour Han and the kids in the best way possible.

“I want to make sure that long after I’m gone, people are still remembering them and who they were, what they brought to the world.”