The enormous cost of raising kids is forcing Aussies to have fewer children – or none at all

In just a few generations, the face of the Australian family has dramatically changed – and the shift looks to be accelerating. There will be consequences for everyone, experts warn.

What price to do you put on a family?

About $30,00 a year per child until they reach adulthood, according to research, and that’s a cost too high for a growing number of Australians.

Several decades back, most young couples were married and starting a family by their early 20s, typically having three or four kids when it was all said and done.

These days, Aussies have children much later in life and are considerably more likely to have just two, with the number of solo child households rapidly on the rise.

The country’s birthrate has collapsed so much that it’s running below ‘replacement’ levels – that is, without immigration, the population would be declining.

“Having children is a life-changing and joyous experience for most parents, but it also comes with added expenses that can push the budgets of even the savviest savers,” finder.com.au money expert Gary Ross Hunter said.

Analysis by the financial comparison website of various measures put the cost of raising a child between $159,000 and $548,000 over the course of 18 years.

In-depth research from the University of Canberra modelled three different family scenarios to give an indication – low-income, middle-income and high-income households.

“It found that the cost of raising two children would likely range from $474,000 to $1,097,000 over the course of their childhood,” Mr Ross Hunter said.

For one kid, that’s a range of $13,166 to $30,472 every single year.

Amid a cost-of-living crisis and continually worsening housing affordability, the pretty penny parents are forced to find to manage a family could be why three has become the new two.

And it’s why for many, two is at risk of eventually becoming one – or maybe even none.

More would be nice

The motivation for having a smaller family comes down to a number of factors, from lifestyle to career ambition and ability.

But research suggests that money plays a big role.

A survey conducted for insurance comparison site Choosi found the majority of Australian couples who want kids are aiming for two.

“However, most couples (84 per cent) planning to start a family felt the cost of having kids has impacted the number of children they are planning to have,” Choosi’s Cost of Kids Report in 2023 found.

That finding mirrors the one made by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), published in its groundbreaking report titled ‘It’s Not for Lack of Wanting Kids’.

“The issues that were most likely to be considered particularly important when thinking about having children were the capacity to support a child financially and the capacity of each partner to be good parents,” it found.

“Despite Australia’s economic prosperity, people remain concerned about their capacity to create and maintain a family environment in which children can be nurtured and supported financially and emotionally.”

A separate report released by AIFS in late 2021 gives some stark insight into the concerns facing would-be parents.

Its Families in Australia survey found one-in-six respondents were ‘very concerned’ about their financial situation and one-in-five worried about their future as a result.

Families who rent their home were among the most worried. Overall, 21 per cent of households with kids had to ask family or friends for financial help.

“The issues reported on in the survey around financial wellbeing included the costs of living now and in the future, having enough savings for retirement, loss of employment or reductions in work hours, physical and mental health issues and providing financial assistance to family members,” the report found.

Leith van Onselen, chief economist at MB Fund and MB Super, and co-founder of MacroBusiness, said the trend of fewer kids shouldn’t come as a shock.

“Australia’s housing costs are among the highest in the world, having more than doubled relative to incomes over the past 30 years,” Mr van Onselen wrote in analysis for MacroBusiness.

“Australian households are carrying the world’s second highest debt loads, behind Switzerland.

“And because most Australian households are on variable rate mortgages, with the remainder short-term fixed, they are spending more of their disposable income on debt repayments.

“Meanwhile, the real household disposable incomes of younger Australians have fallen at the fastest pace in history.”

The higher cost of housing – whether buying or renting – coupled with falling or flat income growth in recent years have “made it uneconomic to have children in Australia”, he said.

Kids aren’t cheap

Raising a kid is getting more expensive, with research by Suncorp Bank finding the cost of having has leapt by 10 per cent in the previous five years.

And as Choosi’s research pointed out, that’s only getting worse, with almost half of couples planning to start a family reporting factors like the cost-of-living crisis as having impacted their decisions around when to have kids.

As a result, 26 per cent of those couples have delayed starting a family by up to two years.

The Choosi research found the heftiest costs of having kids are childcare, nappies and hygiene, and groceries.

As children grow up, households will spend an average of $875 per year on sporting and exercise activities, and another $779 on extra-curricular learning or tutoring.

When high school arrives, those wanting to send their child to a private school can expect to fork out about $23,000 per year, according to Exfin analysis.

“The trend over recent years had been for the increase in private school fees to significantly exceed wage and wider inflation, and while this paused during the Covid pandemic, significant increases around or above appear the norm in 2024,” it reported.

“We expect continuing financial pressure from increasing wage costs and a school building construction boom in recent years that can only be described as exorbitant.”

Depending on where a family lives and the prestige of the school in their sights, the amount required can be eye-watering.

For example, parents of a Year 12 student spend a small fortune to send them to Sydney Grammar ($44,000), Brisbane Grammar ($34,000), or Melbourne Girls Grammar ($41,000).

But that’s just for a single year of schooling.

The Futurity Investment Group Cost of Education Index has revealed that in Sydney, the most expensive capital for schooling, parents will pay an average of $377,993 over the course of a child’s education at a private institution.

Add the ever-growing cost of housing on top of that and the fiscal deck of cards starts to become shaky.

According to SQM Research, the median asking price for a home in Sydney has hit $1.45 million while the median weekly rent is now $836.

In Melbourne, buying a home at the median asking will set you back about $1.03 million while the cost of rent for a dwelling sits at $623 per week.

Things aren’t much better in Brisbane. The median asking price for a home is $931,000 while the median weekly rent is $652.

How things have changed

Back at the start of the 1980s, women were considerably more likely to have three or more children (58 per cent) than two (25 per cent).

But according to the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS), family sizes have become smaller and smaller over recent decades.

The most common family size these days is two kids, with larger families of three or more little ones are much less common.

At the same time, the number of families with just one child has been on the rise for some time now.

That’s reflected in the official birthrate released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics – just 1.67 babies per woman in 2022 and marginally above the all-time record low 1.59 in 2020.

“The total fertility rate level required for replacement is currently considered to be around 2.1 babies per woman to replace herself and her partner in the absence of overseas migration,” the ABS noted.

That is, if it wasn’t for immigration, Australia’s population would begin to decline due to the current birthrate.

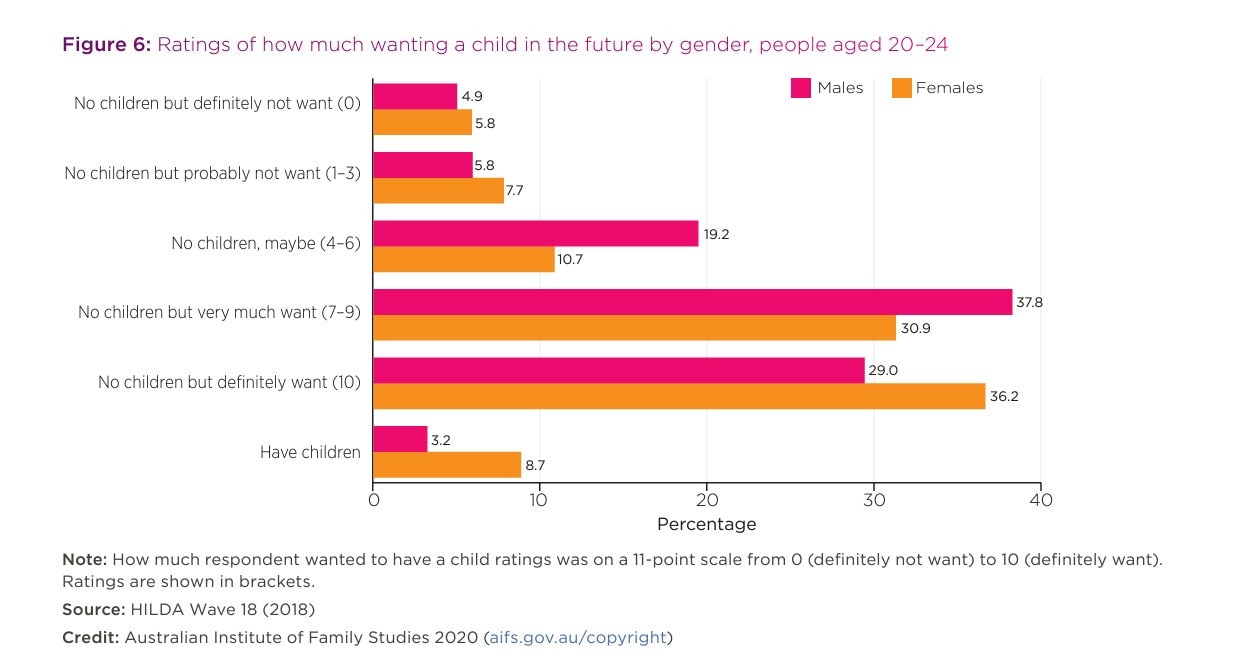

“The age at which women have their first child has risen substantially over time,” the AIFS noted in its Having Children report in mid-2020.

“While few young people in their early twenties had children, most indicated they want to and were likely to have children in the future.”

But the number of kids people actually want has also reduced dramatically.

Mums fall behind at work

It’s not just the ongoing cost of kids that might be behind changing attitudes, but also the financial and career progression toll they take on mums.

Research by the Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce found mums are almost three times more likely than dads to work in flexible arrangements in order to manage childcare responsibilities.

“About 80 per cent of mothers with a child under two who had returned to work were using some form of flexible working arrangement to manage caring responsibilities, compared to just 28 per cent of fathers and partners,” it found.

Two-in-three working parents put their careers on hold when they have kids, and of those, 40 per cent later have regrets about making their jobs less of a priority, the AIFS found.

Extended time away from work while on maternity leave and then a reduction in hours worked are both attributed with stifling career progression and remuneration increases.

The impact on future Australia

There are some big potential consequences of a falling birthrate and without adequate planning and preparation, Australia risks being left behind.

That’s the warning of Leah Ruppanner, a sociologist and lecturer at The University of Melbourne, who said a “sub-replacement” fertility rate describes a scenario where, without overseas migration, the country’s population would begin to decline.

“Sub-replacement fertility is important for governments,” Ms Ruppanner explained in analysis for The Conversation.

“Entitlements are skewed to the old and young, which requires a robust middle-aged workforce to support these dependent populations.

Without two children to eventually support their two ageing parents through tax dollars and direct care, governments have insufficient resources to meet their dependent populations’ economic and care demands.”

Basically, without sufficient births of flinging open the border to working-age immigrants, there could be severe economic and social ramifications.

“Children bring great joy, enrichment and hilarity, yet the demands of modern children and work are contradictory,” she said.

“Without adequate policies to support parents, including those who work, the gap between desired and actual births will remain and possibly grow.”