How a Neo-Nazi got out of Sweden's most powerful white supremacy group

ONE in 10 Australians are racist. Having been part of Sweden's most violent white supremacy group, Robert Orell knows what it's like to feel that way.

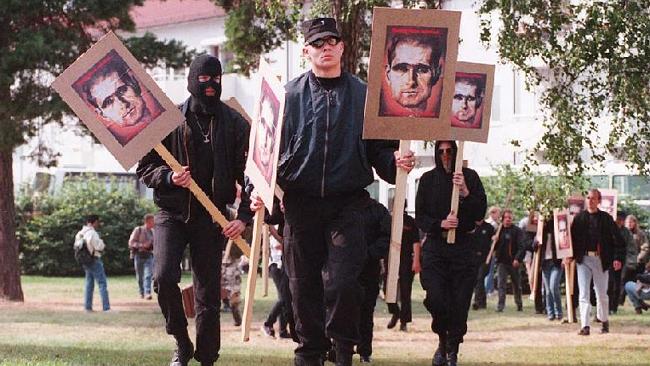

WHEN Robert Orell, 33, was in his early teens, he became involved in a white power movement. To put it bluntly, Orell was a neo-Nazi.

Neo-Nazis seek to revive Nazism, the white supremacist movement made notorious by Adolf Hitler in the 1930s and 40s. The movement is characterised by its violence, racism and xenophobic attitudes.

"When I first got involved, Xenophobic parties were not uncommon in the government, you had serious shooting of immigrants, a lot of attacks on asylum seekers, that sort of thing," says Swedish-born Orell. "We also had a popular youth culture focusing a lot on nationalism, on Sweden being the land of the Vikings, and during that time the racist groups started to recruit young Swedes if they saw an interest in nationalisms or history, that kind of thing. It was a natural base for recruitment.

"I was a fairly insecure teenager, and I was hearing these messages about being special, about masculinity, about being a strong, cool Viking, and I felt attracted to that message. I also had a lot of personal troubles at that time - school failure, conflicts, that kind of thing, and my perception is that this group came at the right time for me, when the message I wanted to hear was 'You're special, you're part of a cause, we need you, we have a purpose for you.'

"It wasn't intellectual - it was connection on an emotional base. I was prepared to die for these people, for this, it was so strong. Everything made sense, like a piece of a puzzle. I knew my friends, I knew my enemies, it all was so clear."

Indeed, seeking belonging and a sense of purpose are some of the reasons why many young people become involved in white power groups all across the world, including Australia.

"Recruitment isn't about ideology - it's important but it's not the primary factor of recruitment," says Orell. "You recruit people by offering a sense of belonging, a community. Looking at the radicalisation research globally, this notion comes up time and time again - with violent Islamic groups, for example, you see the same type of patterns."

"The research we rely on shows that recruitment is certainly about identity, and it's that younger demographic who are likely to get involved in white supremacy groups," agrees Priscilla Brice, Managing Director of All Together Now, an anti-racism charity tackling recruitment by white power groups in Australia.

"One in 10 Australians have racist attitudes, and believe that there are people who don't belong in this country because of their cultural background or ethnicity, according to the Challenging Racism study done by the University of Western Sydney. These attitudes are apparent online in chatrooms, in posters around cities, there's a White Supremacist concert in the Gold Coast every May, and there was one in September in Melbourne too. It's concerning," says Brice.

In Australia, All Together Now seek to undermine recruitment into white power groups by targeting young men who are on the periphery.

"More or less, all extremist environments are male dominated," says Orell. "They're masculine focused, the heroes are men, females are there to support the men. One of the girls I knew had two views of women - that they were either baby machines, or they had to be ten times as tough as the guys to match up. That was her description of it."

All Together Now brought Orell to Australia to share his story so that young men who are involved might be dissuaded from joining groups.

So how did someone like Orell, who was so heavily involved in the white power movement for so many years, actually leave?

"It's not like it used to be," says Orell who currently heads up Exit Sweden, an organisation which provides support and rehabilitation for Neo-Nazis. "Since Exit started in 1998 in Sweden I have seen a lot of positive changes. Nobody thought you could leave the movement - once a Nazi always a Nazi, that kind of thinking. But today people know that you can go through all kinds of situations - drugs, gangs, extremism - and you can come back. That's a real shift in thinking.

"For me personally, in one way it was like a release to leave, but in another way it was really hard. I went into the military with the idea to get military training for the 'coming revolution'. But when I was in the military I realised, I don't want to go back to [my old] life.

"I started reflecting on my life, my comrades. These environments are very good at double standards - they say a lot of things that are very holy, and you can't break the rules. But people do. I had friends who robbed other Swedish people for money, who drank beer, but we weren't supposed to take drugs or commit crimes, unless they're for 'the cause'. To use steroids was looked down upon because one of the consequences is that you might become impotent, which meant you can't have white children, which destroys the cause.

"The tough part was, this is a very sectarian environment and you're in it 24/7. These environments are so destructive. They foster hate and aggression, and you can't live like that for a long period of time. You think and you breathe and you eat the ideology and the movement and the world view, and when you want to leave you have a feeling of emptiness. I was really uncertain of my competencies, my interests, what I want to do or where I want to go. I thought, society won't want me back, I have no place there. I had no education, I was very unsure. That's why I am trying to use my experience in a good way - I didn't just waste all these years, I can use my experiences from that time to help people get out."

Both Orell and Brice agree that the thing that takes people out of white power groups is the same thing that attracts them to them - relationship.

"If you are an active white power member, you wouldn't get disengaged by a message on a board or a pamphlet - to make change you have to make relationships. These people who are in this sectarian environment and are so heavily influenced by the people around them, need other people to help them get out. This is what organisations like Exit Sweden and All Together Now help with - relational networks, be they formal, with professional relational workers like school counsellors, or informal. There's tonnes of research from the last decade on exit strategies and de-radicalisation, and this is one of the areas we have seen works.

"Seeing people let that hate go is such a relief," says Orell. "It makes a change in your relationship with others, with yourself, all these things, when you let that hatred go.

"There are two messages I want to get out in doing this. The first is that it is possible to understand and respond to these white supremacy environments if you have proper knowledge of radicalisation and the relational networks. The second is for people in the movement, that it is possible to get out. Society will take you back. You can make that change."