Why my adenomyosis went undetected for five years

It’s a debilitating condition that leaves a third of Aussie women in frequent pain. So why have so few people heard of it?

“I finally have an answer for you,” my doctor said as I settle in a chair in her tiny office.

I almost don’t believe her.

It’s been five years since I first sought advice for the crippling periods, pelvic pain, bloating, fatigue and nausea that had left my body perpetually feeling like a beat up punching bag.

Until now, I have been dismissed by multiple doctors and specialists. One told me it “might be PCOS” (it wasn’t), others said it was “just bad period pain”.

I’d read stories of other women experiencing the same types of symptoms and not being able to find a diagnosis. So when the doctor said she had an answer, I felt the relief course through my body as I realised my experience was finally about to be validated.

“Your ultrasound showed that you have adenomyosis,” my doctor said.

I stared at her blankly.

“What the hell is that?”

A painful journey to a diagnosis

The first time I had an adenomyosis flare up, the pain was so bad my partner thought my appendix had burst. Even his attempt to carry me to the car left me in complete agony, forcing me into a ball and leaving me nauseous. We settled for calling a doctor out to our apartment. We were promised a visit within two hours, but no one came.

The next morning, I tried to explain what I’d felt to my local GP. He told me it was “probably just a urinary tract infection” and sent me away with a script for antibiotics. Knowing I had none of the symptoms of a UTI, I went to a different doctor who ruled it out almost immediately.

This GP sent me for a pelvic ultrasound but, when the results were inconclusive, simply said: “I’m sorry, I’m not sure what else I can do for you”.

This trend of disbelief and medical gaslighting followed through three more GP visits, countless blood tests, another ultrasound, and, finally, a gynaecologist visit that left me in tears.

That appointment began with the insinuation I was overdramatising my pain, quickly followed by an accusation that I wanted “surgery I didn’t need” when I requested a laparoscopy to rule out endometriosis. When I picked up my bag to leave, the parting shot was delivered: “Some women just have pain. We don’t know why. You might have to learn to live with it.”

I lived in pain for three more years, before another GP grew suspicious of my symptoms and sent me for another ultrasound. I wasn’t feeling hopeful, but it finally gave me the answer I needed. Unfortunately, the diagnosis was just the beginning of a long journey to manage the pain.

What is adenomyosis?

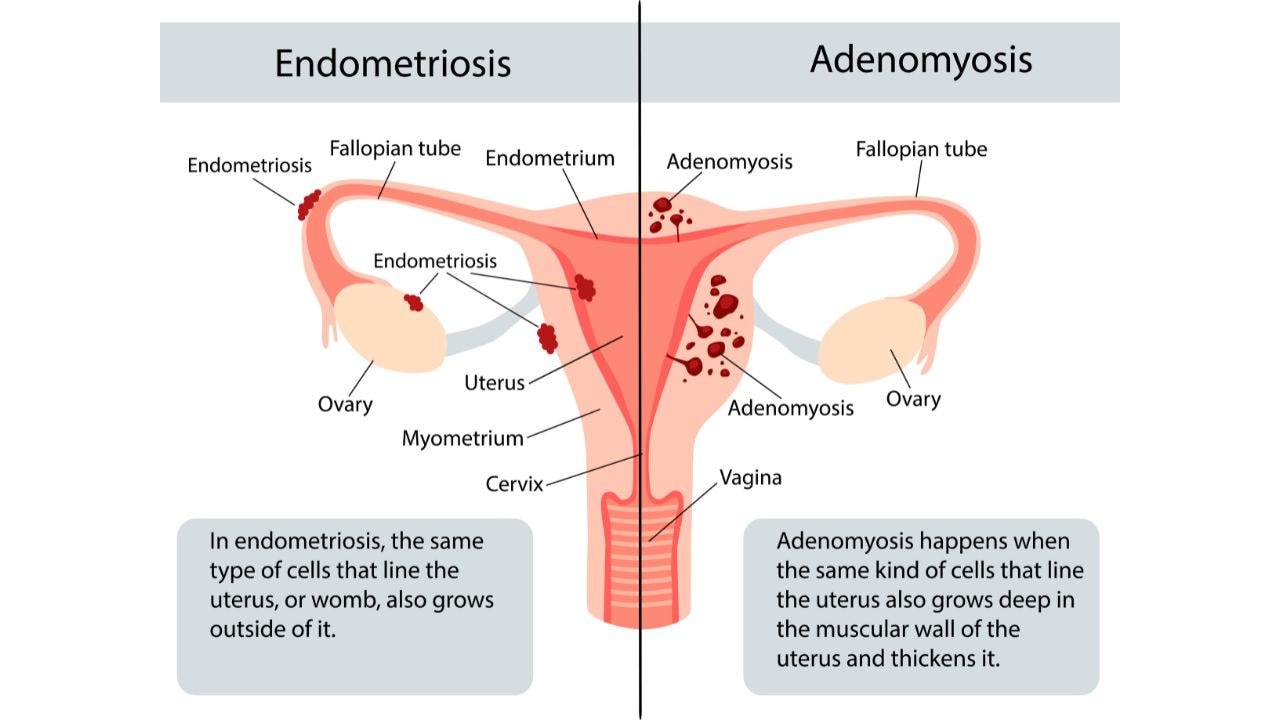

Often referred to as the “evil cousin” or “evil sister” of endometriosis, adenomyosis is a disease that manifests in a similar way, with cells like those that line the uterus growing where they aren’t supposed to.

In endometriosis, they can be found anywhere outside of the uterus, which can cause severe pain and infertility. In adenomyosis, the cells and their supporting tissue, called stroma, are found within the muscular wall of the uterus.

It’s estimated that around 35 per cent of women have adenomyosis, yet surprisingly little is known about the disease.

While some women don’t experience symptoms, many others report painful periods, heavy or abnormal bleeding, pelvic pain and painful sex. But it doesn’t end there.

“There’s more and more evidence to support adenomyosis’ impact on infertility, and possibly also obstetric outcomes for increased risk of miscarriages,” Dr Samantha Mooney, an obstetrician, gynaecologist, and clinical researcher, told news.com.au.

“It can also have an impact on both spontaneous fertility and IVF success rate. Up to a quarter of people who suffer infertility will have a diagnosis of adenomyosis,” she said.

It’s also extremely common for adenomyosis and endometriosis to go hand-in-hand, with some studies suggesting up to 89 per cent of people with endometriosis also have adenomyosis.

Because women have long had their experiences dismissed, both endometriosis and adenomyosis typically take years to diagnose – such as in my case – which can result in symptoms getting worse.

Excruciating delays

Perhaps the biggest reason women are struggling to be formally diagnosed with adenomyosis is that specialists can’t form a unanimous decision on exactly what it is.

Originally seen as a disease that affects those over the age of 40 after childbirth, hysterectomies used to be the gold standard in a diagnosis for adenomyosis. As more and more women in their 20s and 30s have been diagnosed, this has become less viable.

Instead, imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) are most commonly used to find the disease. However, this isn’t always straightforward either.

“We can’t find agreement yet in the international literature as to exactly what constitutes adenomyosis on ultrasound,” Dr Mooney said.

“There’s a group that published something, think of it as a consensus on how we should report an ultrasound, to say whether or not certain features are there with regards to adenomyosis.

“But even findings from these often, very hightech and skilled ultrasounds, we can’t agree whether they’re absolutely specific to adenomyosis or not.”

It’s the same for MRIs.

No relief

Even once you have a diagnosis, things don’t necessarily get any easier.

It took me multiple attempts to find a pain medication that offered me even the slightest bit of relief. Some days, it’s still not enough.

Then there’s the first-line therapy for managing symptoms. Like most conditions that solely affect women, it comes in the form of the contraceptive pill. Once again, this can take a lot of trial and error to find one that works. For those looking to get pregnant, it’s not even an option.

As Dr Mooney points out, there’s also an ongoing cost to it not everyone can afford.

“Only very few of the hormonal remedies that may treat adenomyosis, or at least keep the symptoms at bay, only very few of those are covered by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS),” she said.

Adenomyosis isn’t even listed on the PBS coverage for some of the medications that we use.”

Some surgical procedures may also be considered for adenomyosis, with a hysterectomy used as a last resort for those who haven’t responded to any other treatment.

A painful conclusion

There’s a relief to finally putting a name to your pain.

Unfortunately, this relief is snuffed out moments later with the words “there’s currently no cure for adenomyosis”.

Some attempts are being made to improve the diagnostic process, such as a letter submitted this week to the Journal of Clinical Pathology calling for pathologists to form a consensus on exactly how to diagnose the disease.

But if real change is going to happen, we need to start talking about it.

Endometriosis is finally starting to get the recognition it sorely deserves.

More Coverage

It’s about bloody time adenomyosis did too.

Medicare is failing women and it’s About Bloody Time things changed. Around one million suffer from endometriosis. There is no cure. Help is hard to come by and in rural or regional areas, it’s virtually impossible. We are campaigning for longer, Medicare-funded consultations for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment.