Silent health plague impacting nearly one million Australian women

It’s a crippling disease as common as diabetes, and yet, nearly one million Australians are silently suffering from a condition that specialists aren’t equipped to manage.

More than half of Australian women suffering from endometriosis have felt ignored by doctors when seeking treatment, news.com.au can reveal.

A news.com.au survey of more than 1700 Aussies who suffer from endo found 54.4 per cent of sufferers were dismissed by their health practitioner.

Instead of help, they were offered baffling advice – maybe you should just lose some weight, try having a baby, or seek a psychiatric assessment instead.

An estimated one million women suffer from the debilitating condition, which can cause severe pelvic pain and infertility. There is no cure.

Despite the prevalence of the disease, which is almost on par with the amount of people who have type 1 and 2 diabetes, specialists are ill-equipped to manage pain and Medicare rebates are so low there is no incentive to take time to provide thorough care. An initial gynaecologist appointment currently receives less than half the rebate of other specialist appointments dealing with issues as complex as endometriosis.

The reality for women suffering with the condition is they are rushed through quick appointments and only given two options – either undergo surgery to diagnose and remove the disease (with a high likelihood of it growing back imminently) or be prescribed hormonal treatments, including contraceptives like the pill or Mirena and Kyleena IUD.

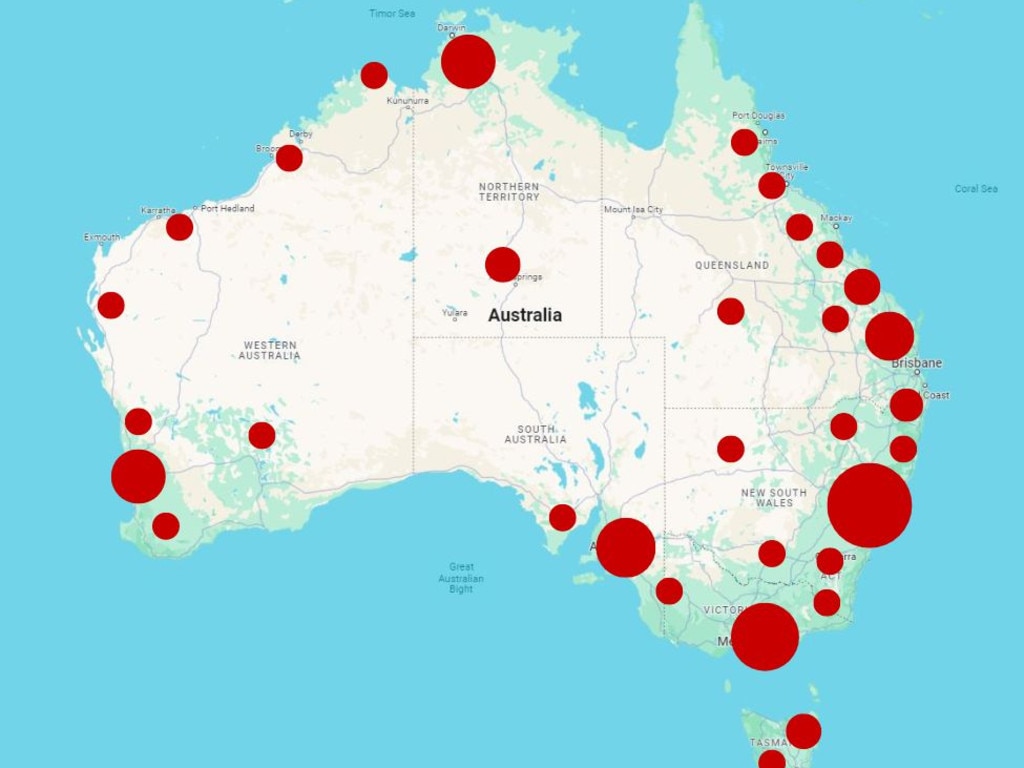

Medicare is failing women and it’s About Bloody Time things changed. Around one million suffer from endometriosis. There is no cure. Help is hard to come by and in rural or regional areas, it’s virtually impossible. We are campaigning for longer, Medicare-funded consultations for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment.

‘Lack of understanding from doctors’

Our survey results reveal a significant delay in women receiving a formal diagnosis of endometriosis.

Only 32.23 per cent were diagnosed within six years, while 45.4 per cent endured a wait of more than six years, while 22.4 per cent are still awaiting a formal diagnosis.

Medical experts credit this to a lack of understanding from most doctors and specialists, who have no motive to upskill in pelvic pain.

Advocates believe the silent plague of endometriosis – which costs the Australian economy $9.7 billion in lost productivity annually – stems from the pervasive taboo surrounding women’s health issues, which contributes to a lack of awareness, funding and research.

“Gynaecologists are paid to do surgery, they aren’t paid to talk, yet it is not being listened to that is the major grievance women have,” Associate Professor Dr Susan Evans told news.com.au.

“The most important part of patient care is taking a good medical history of the condition, explanation and education for the patient, and working together to make the most effective plan. This takes time and wisdom.

“This is what is missing.”

Former Channel 9 newsreader Julie Snook, who has had laparoscopic surgery to treat endometriosis 13 times, is just one sufferer who told us she felt gaslighted by doctors for years.

“Every time I was wheeled into surgery, I felt like I was wasting everyone’s time,” Snook says.

One in six women have lost their jobs due to managing their condition, while one in three will be overlooked for a promotion, according to Endometriosis Australia data.

‘It looks like concrete has been poured onto the pelvis’

Endometriosis is a disease in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside it, usually in areas like the ovaries and fallopian tubes as well as on organs such as the bladder, bowel, vagina and cervix, causing severe pelvic pain and fertility issues.

In several extreme cases, it has even been found in the lungs and brain.

It presents in four stages – stage 1 being mild, while stage 4 is extreme. However, stages don’t indicate the level of pain a woman can feel.

“Stage 1 is small amounts of disease that may be scattered in different areas. So it may just be between the bowel and the vagina, to finally stage 4 disease, where it looks like someone’s grabbed some concrete and poured it into the pelvis where you really can’t tell the difference between ovary, uterus or any other organs,” Associate Professor Dr Anusch Yazdani says.

About 40 per cent of the 1700 women surveyed by news.com.au reported that they had experienced infertility.

“Endometriosis is mostly on the reproductive tract, that means the uterus, the ovaries and (fallopian) tubes. So it would make sense that if the disease progresses, there’s an obstruction to the sperm and the egg getting together,” Dr Yazdani says.

“Endometriosis also affects the function of those structures. We know that women who have endometriosis experience more cramping in the uterus, and we know that the (fallopian) tubes don’t work as well. We also know that there are different hormonal effects of endometriosis.

“When women are having treatment for endometriosis, particularly medical treatment, almost all of those medical treatments affect fertility while they’re on them.

“And then lastly, we know that if you have lots and lots of pain, it’s not a great time to be having sex, so women who are affected by pain would also have problems falling pregnant from a functional point of view.”

Endometriosis and diabetes: The difference in care

The two diseases are frequently compared due to their similar incidence rates, yet diabetes is given a greater level of attention and funding over endometriosis, a condition that uniquely impacts women.

During 2023, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Australia’s peak medical funding body, were paying four grants for endometriosis research with a combined cost of $1.43 million, with one new grant awarded for $841,760.

In comparison, diabetes, which affects 1.3 million Aussies, had 22 active grants for Type 1 of the disease at a cost of $8.3 million, and $18.4 million for Type 2 from 72 grants (with some possible overlap).

Between 2015 and 2022, the NHMRC spent $6.4 million on endometriosis, and $530 million on diabetes research.

“Quite often, endometriosis will be compared with diabetes, purely because of the incidence. But the fact that endometriosis typically only affects women and diabetes doesn’t … It is quite frequently compared,” University of New South Wales (UNSW) PhD Candidate Kate Gunther said.

“Money is important always, and I don’t want to harp on that we’re so hard done by because every researcher needs money. But I think if you look at the numbers, it’s really outrageous how disparate it is.”

Ms Gunther, who is in the UNSW Gynaecological Cancer Research Group, said a lack of incentive to study endometriosis and pelvic pain meant most researchers and doctors would only go into the sector as a passion project, or a side hustle.

“Endo is quite frequently seen as something additional. It’s not its own specialty. It’s embedded within gynaecology,” Ms Gunther said.

“We need multidisciplinary teams, and so, to incentivise people to be able to do that, it should be seen as a legit thing independently.

“In the research space, a lot of the teams – I’m the only dedicated endometriosis researcher in a cancer group – and it’s quite often seen as, ‘Well, you’ll do cancer and a bit of endo’ or, ‘You’ll do fertility and a bit of endo’. It’s not really seen as its own specialty.

“There is not a ‘purely’ endometriosis group where that is all they do in Australia. I can say that with confidence. Unless you’re looking at clinical groups, but they’re still delivering babies (as well).

“The more I learn about it as a disease, it is insanely complex, and it really shouldn’t be an extra.”

Ms Gunther pointed out how, in almost every other medical field, there were specialists across different diseases.

“You go to an oncologist, and there’ll be a specialist in melanoma. So not only are they a cancer specialist, but they are a skin cancer specialist, and not even skin cancers in general, just melanoma,” Ms Gunther explained.

“We don’t really have an equivalent in gynaecological care.

“There are people who have ended up focusing on something because they care about it, but it is not a structural implementation of taking this condition seriously and giving it the resources that it deserves.”

The federal government committed $58.3 million for endometriosis and pelvic pain in the 2022-23 Budget, which included the establishment of 22 dedicated Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Clinics across Australia.

At the Bendigo clinic in Victoria, which opened in October last year, there were reportedly already 300 patients before doors even opened.

Dr Cecilia Ng, a researcher and senior lecturer at the School of Clinical Medicine, UNSW Sydney, pointed out how women’s reproductive organs are among the most complex health studies, but the taboo around widely discussing “period problems” meant the sector was still falling behind.

“There is the potential of people still saying, ‘Oh, here we go, here are females talking about their issues again. They’ve just got to put up with it’,” Dr Ng said.

“With women’s health, it really comes down to talking through it and going through the process in depth, and that takes time.

“Unfortunately with the way the rebates happen, it’s more procedural-based rather than actually taking the time to spend with patients to work it out, which is why we’re seeing all the issues with GPs and bulk billing. You can’t get through a whole set of women’s health history within 15 minutes.”

About Bloody Time is an editorial campaign by news.com.au that been developed in collaboration with scientists recommended by the Australian Science Media Centre, and with the support of a grant from the Walkley Foundation’s META Public Interest Journalism fund.