Group of Aussies who are $50,000 worse off for infuriating reason

Thousands of people across the country are now $50,000 poorer than the average Aussie – and the reason should make you mad.

There are thousands of Aussies across the country right now who are $50,000 worse off than the average person, all because of one devastating reason.

One in nine people suffer from endometriosis, a condition where tissue similar to that which normally lines the uterus grows in other parts of the body, usually the pelvic region.

For the nearly one million people living with it across Australia – along with the countless others thought to be suffering in silence – symptoms like excruciating pain, fatigue, excessive bleeding and infertility are something they are often forced to manage daily.

On top of this, women are also saddled with the financial burden that not only comes with getting ongoing treatment – as there is currently no cure – but also just trying to get diagnosed in the first place.

Medicare is failing women and it’s About Bloody Time things changed. Around one million suffer from endometriosis. There is no cure. Help is hard to come by and in rural or regional areas, it’s virtually impossible. We are campaigning for longer, Medicare-funded consultations for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment.

As part of the About Bloody Time campaign, news.com.au surveyed more than 1700 people who suffer from endometriosis to gather insights into how it affects their lives.

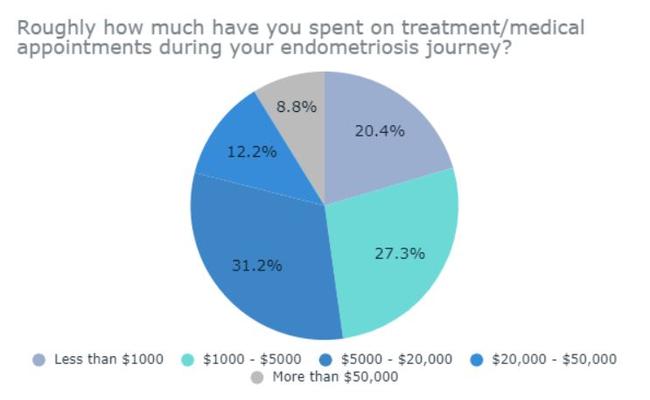

From those responses, 8.8 per cent – almost one in 10 – revealed they had spent more than $50,000 on treatment and medical appointments as a result of their endometriosis journey.

Almost a third of respondents, 31.2 per cent, estimate they have spent between $5000 and $20,000 and a further 12.2 per cent put the cost between $20,000 and $50,000.

On average, it takes seven years to be diagnosed with endometriosis and, for many, it is often longer, with 22.4 per cent of people saying they are still waiting on a formal diagnosis.

It can be incredibly difficult for women to be diagnosed, with many reporting feeling gaslit by medical professionals and having their pain brushed off as “just a bad period”.

For Ella Collings, 24, it took 10 years of doctors telling her she “just had anxiety” or IBS before she was finally diagnosed.

During this time she was also told she was “being dramatic” and it’s “just what women have to go through”.

By the time Ella was diagnosed, she had Stage 4 endometriosis, which had spread so far through her body that it was found on her bowel.

“It basically was everywhere. My body was just riddled with it,” she said.

Melbourne woman, Chloe Jackson, spent nine years trying to get a diagnosis before she was finally taken seriously by doctors.

“The GP I was seeing at the time insisted I just had IBS but I pushed for more testing and my endometriosis diagnosis came about,” the 27-year-old told news.com.au.

From the survey, 54.4 per cent of people said they have had mostly negative experiences with doctors and medical professionals when seeking treatment for endometriosis symptoms.

Shockingly, 17.3 per cent said they had never been taken seriously when seeking medical help for their condition.

Many women revealed their doctor’s immediate response to their pain was to “go on the pill”, “lose weight” or even urging them to get pregnant to “stop the pain”.

One respondent said she was told: “You’re a young, pretty girl don’t worry about it.”

Another said at the age of 16 she was told to “have a baby and it would sort itself out”.

Many other women reported being accused of exaggerating or making up their pain in an attempt to be prescribed drugs.

Another was told that heavy, frequent periods were normal and “meant to be painful”.

“A male doctor told me how inconvenient this was going to be for my husband because it would cause issues with how much I could work, do chores, have sex and children, and that I should bring him to next appointment so he could explain it to him,” one respondent said.

It isn’t just in a medical setting that women are being gaslit and brushed off, with many also living in fear of repercussions in their professional life.

According to Endometriosis Australia, one in six people with the disease will lose their employment due to managing endometriosis.

The majority of survey respondents – 57.1 per cent – said they had chosen not to reveal their diagnosis to their employer. This is despite more than 83 per cent saying they have had to take time off work due to their endo.

Depressingly, the experiences of women who had confided in their workplaces about their diagnosis proves exactly why so many are reluctant to tell their bosses.

Common responses revealed employers often acted with annoyance, frustration or even claimed that it was “just a painful period” and advised the employee to take pain killers and keep working.

Other women revealed they felt “humiliated” after disclosing the information, with one person saying her male employer asked for “very personal” information that she was later told by a doctor she didn’t need to disclose.

Another person said: “I recently passed out in the bathroom due to pain and when I came to, I was weak and shaking and vomiting. I was told that time would come from my lunch break.”

Many revealed the decision to be open about their diagnosis led to them becoming jobless.

“I lost my job because I took too much time off,” one said.

“They were reasonable at first but eventually fired me for needing to take so much time off,” another wrote.

Endometriosis can impact every aspect of your life, with these being just some of the experiences from the almost one million Australians who live with the disease.

The year-long struggle most suffering face to even get diagnosed means right now there are countless women across the country still struggling to get answers.

The likelihood of getting a diagnosis and treatment dwindles even more for women who live in rural areas.

About Bloody Time is an editorial campaign by news.com.au that been developed in collaboration with scientists recommended by the Australian Science Media Centre, and with the support of a grant from the Walkley Foundation’s META Public Interest Journalism fund.