Brutal reality of life for 29 per cent of Aussies laid bare in just eight words

Millions of Australians have been issued a five year warning, with a map exposing a brutal truth that keeps being ignored.

The brutal reality of life in rural and regional Australia has been laid bare in one sentence from an academic specialising in women’s pain.

“There’s a saying in Darwin, because there are just no experts or specialists: ‘If you’ve got pain, get on a plane,’” UNSW PhD candidate Kate Gunther tells news.com.au.

“You can’t find the care that you need.”

Diagnosis of endometriosis, which affects one in nine Australian women, takes an average of seven years because of its difficulty to pinpoint and treat. There is no known cause or cure.

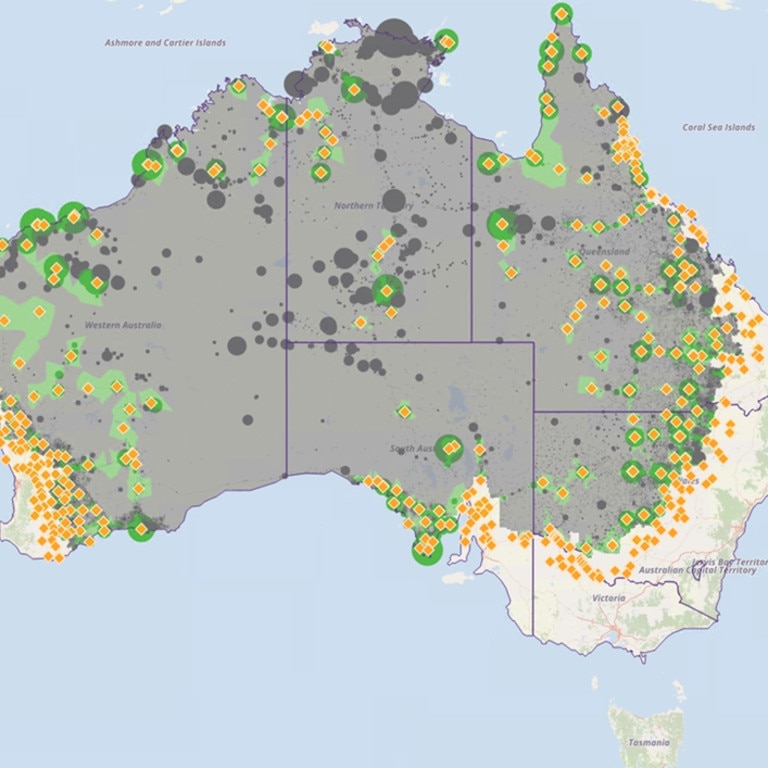

The barriers to diagnosis are only magnified the further people live from a capital city – around 29 per cent of Australians reside in a rural or remote area, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Those affected by endometriosis in these areas not only face limited access to services, but often no access whatsoever to specialist care, necessitating hundreds of kilometres of travel just to seek an opinion.

For Prue Luck, a pharmacist who lives on a farm in Central Queensland between Rockhampton and Biloela, it’s impossible “to put a number to how much my endo has cost me – it’s too high to count”.

The 27-year-old has spent the decade since she was diagnosed with the “silent but destructively life-changing” condition travelling to Brisbane and Toowoomba, in the state’s southeast, for treatment.

“To travel for treatment means I have to take days off of work. Overnight accommodation is required, which also incurs a cost,” Ms Luck, who was informed after her third laparoscopy that her body was “riddled” with the disease, tells news.com.au.

“A standard visit just to see my doctor can easily cost $100 to $200 each way in fuel, or a plane ticket, plus a $150 to $200 appointment fee, plus a $200 to $250 hotel room fee, plus food expenses.”

“People (in the major cities) are always like, ‘We need more surgeons, we need more specialists’,” Ms Gunther, a member of the UNSW Gynaecological Cancer Research Group says.

“But what about the people who can’t even get in to see a specialist?”

Dr Dani Stewart is the principal doctor at Northside Health NT — the only clinic in the Northern Territory that received funding to become one of 22 dedicated endometriosis and pelvic pain centres across Australia as part of the 2022-23 federal budget, which committed $58.3 million to the conditions.

The demand for such clinics was apparent before doors even opened. Dr Stewart tells news.com.au “nearly all” of Northside Health’s patients since August have been from within Darwin, due in large part to a sizeable waitlist. It was a similar story in Bendigo, Victoria, where there were reportedly already 300 patients before it opened to the public in October.

NSW MP Helen Dalton, the Member for Murray, tells news.com.au there is a “massive need” for specialist endometriosis care, particularly in remote and regional areas where residents are “flat out to even have a (general practitioner)”.

“There’ll be no doctors in the bush in five years. That’s how serious it is. It’s a travesty,” Ms Dalton says.

She refers to one week in February, during which not a single doctor was rostered on at the district hospital in Leeton, which has a population of 12,000, forcing nurses to redirect patients “to Griffith or Wagga”.

“I’ve got to wait at least six weeks to get a (GP) appointment. Let alone a gynaecologist,” Ms Dalton says.

“We haven’t got a gynaecologist in Griffith, I don’t think. Or an obstetrician … We are really regarded as third world as far as women’s health issues. And doctors just don’t want to come out here and work because they’re not supported.”

Ms Luck says access to a “good GP” is the “first barrier” for rural women with endometriosis.

“With an extreme shortage rurally, it’s hard to see one — let alone find one who will listen to your period problems and send you off to a gynae,” she says, noting that the closest gynaecologist who specialises in endometriosis is a seven-hour drive — or one-hour flight — away, in Brisbane.

“Getting referred to one is hurdle number one, then getting to them is hurdle number two. This all sounds like a lot of effort, so for many women, they will put it on the back burner or delay it.”

Adjusting to “the lack of specialists that you have access to, and the lack of services in general”, Dr Stewart says, is an “unfortunate” reality for Australians who “live outside of the big cities”.

“People have to travel large distances to get the high level of expertise provided that people in main cities have very quick and close access to. Wait times are also longer for people in these areas,” she says.

“It is particularly hard for people who don’t have private health insurance. And even if you do have private health insurance, you’re still paying the cost of airfares to go and have something like a specialist ultrasound.”

Cairns woman Grace Kerr estimates she’s spent between $50,000 and $60,000 doing just this.

The 37-year-old was told that in order to have all of her endometriosis removed, she’d have to travel to Sydney. She’s since flown to the NSW capital on four separate occasions. In April, Ms Kerr will fly down again — this time, for her fifth excision procedure.

Each of these trips, she tells news.com.au, entail the cost of flights to and from Queensland, as well as one or two nights’ accommodation. In the interim, she sees a naturopath, and a physiotherapist for clinical reformer pilates — “symptom management” to help counter her pain.

Treating her endometriosis, Ms Kerr says, has “basically taken all my savings. I was saving for a home, or a European holiday, and it had to go on my surgery instead. It’s an expensive disease to have”.

It’s an almost unthinkable price to pay for a condition she says she’s “never been without any pain from”. Sometimes, it feels like “a meat grinder in my pelvis” — other times, like “I’m carrying a bowling ball around in there”.

“But it gets to an eight or nine level, and then I’m like, ‘OK, I need surgery’,” Ms Kerr says.

“And then it’ll come down to a (level) three or four after surgery, and that’s tolerable. You can live with that. You get used to it. It’s just when it gets to the severe points that you need help with it.”

This mentality, Dr Stewart says, is one “we see all the time in patients in the Northern Territory”.

“People present later, with a whole range of conditions, because they tend to put up with their pain until they really can’t ignore it any longer,” she says.

As a teenager, Amelia Mardon’s parents would drive the three-and-a-half hours from their home in rural South Australia to Adelaide so she could receive care for her endometriosis.

“Luckily, growing up in a relatively middle class family, they could afford (for) me to have the surgery, and pay for the medications, and pay for the physio,” the 26-year-old, whose PhD has looked into the role of pain science education for people with pelvic pain, tells news.com.au.

“But it’s so bloody expensive, and people aren’t eligible for any type of funding or rebate.

“The healthcare system is not set up well at all to manage endometriosis, but also chronic conditions in general. Being on the waitlist for years upon years for a surgery, or even to see a specialist is not OK at all. The inequities there are just not acceptable.”

Longer, Medicare-funded consultations for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment, Dr Stewart says, are “critical”.

“Nearly everyone I know who does general practice does it because they love that way of practising, and they want to help people. They’re not doing it because they want to make money,” she says.

“Having said that, we have to be realistic and respectful of GPs – they’re not charities that are providing free services based on need, because endo is a massive need, but GPs are dealing with terrible situations every day.

“It’s just a reality that doctors need to be paid for the work they do … because they are interested to do the work, but there is a bottom line for people. And they need to be able to do important work like this without it compromising their incomes.”

The current trend toward short appointment times “is not helpful at all”, Ms Mardon says, barely scratching the surface when it comes to addressing the needs of someone with endo.

“A consult is where you get your patient’s history. You listen, you validate, you find out what the patient wants and needs, their goals – so you can actually tailor and make a pain management plan, or a management plan for their endo in general,” she says.

“Without that, how are you meant to cover everything and actually give good care?

“These longer appointment times – if that can be incentivised, I think that would be a really good step.”

Medicare is failing women and it’s About Bloody Time things changed. Around one million suffer from endometriosis. There is no cure. Help is hard to come by and in rural or regional areas, it’s virtually impossible. We are campaigning for longer, Medicare-funded consultations for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment. Read more about the campaign and sign the petition here

About Bloody Time is an editorial campaign by news.com.au that has been created in collaboration with the Australian Science Media Centre, and with a grant from the Walkley Foundation’s META Public Interest Journalism fund.