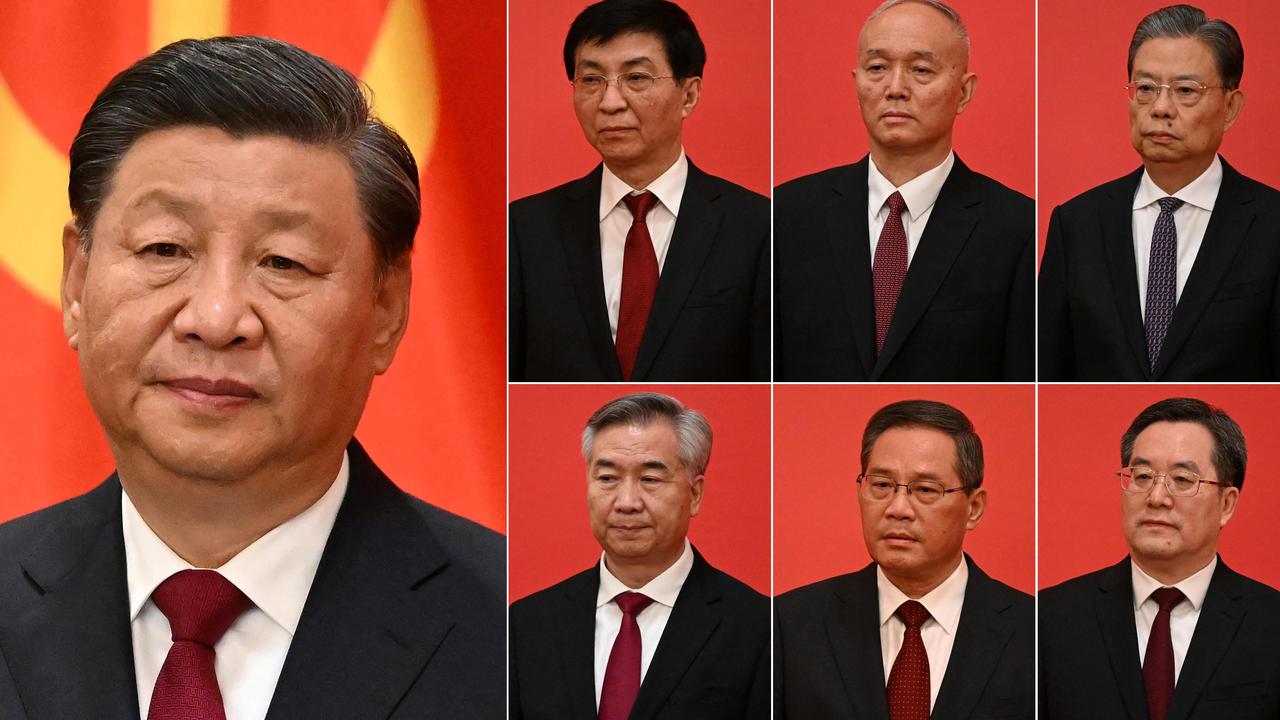

‘All Xi’s men’: The six powerful figures standing alongside China’s new ‘emperor’

Xi Jinping has cemented his role as a “modern emperor” with an astonishing power grab. This is the mindblowing prediction about how long he will reign.

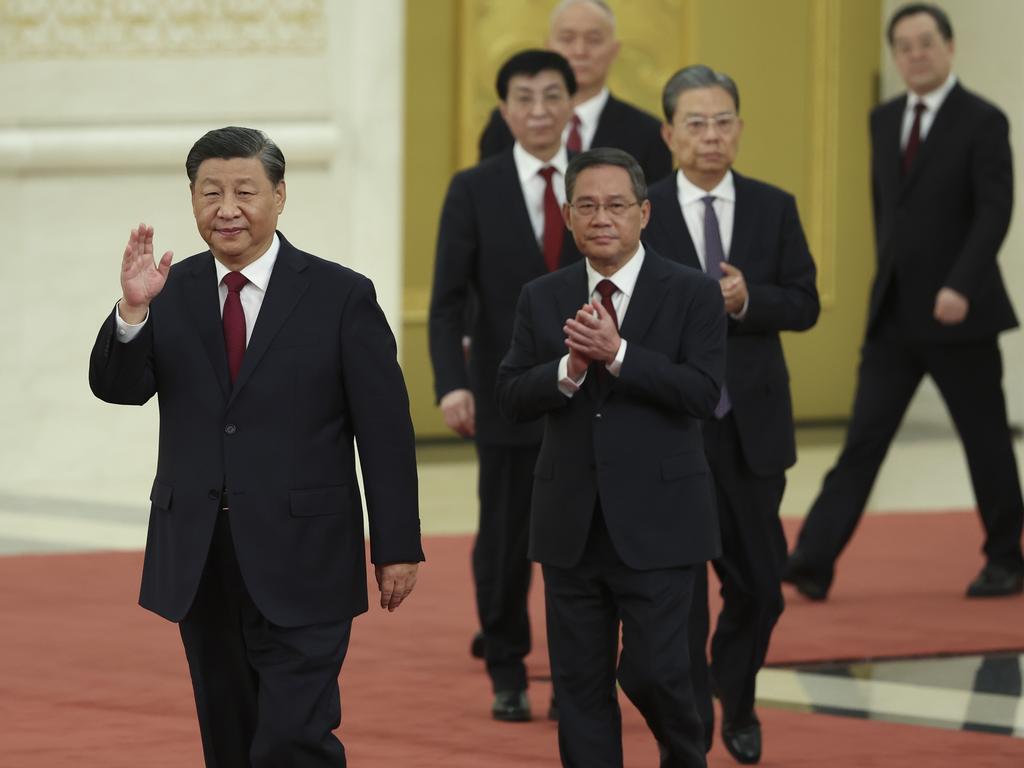

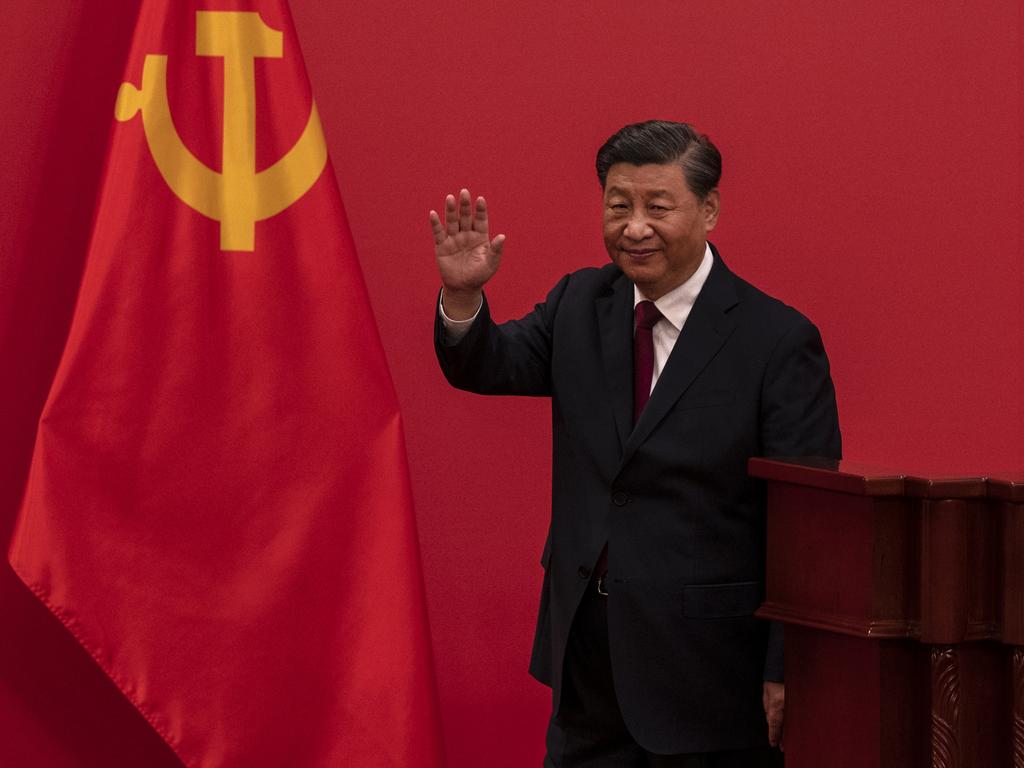

Xi Jinping unveiled his new leadership team on Sunday in a power grab cementing his role as a “truly modern emperor”, as China’s leader secured an unprecedented third term in office.

The Chinese Communist Party’s seven-member Politburo Standing Committee, headed by Xi, is traditionally made up of representatives from all factions of the party. But the team presented by Xi on the weekend is stacked with loyalists who owe their careers to the 69-year-old leader.

Representing the apex of power in the communist nation, the seven men will rule Beijing for the next five years as Xi tightens his grip, in the face of growing tensions with the West and mounting economic woes at home.

“This is what complete dominance looks like,” wrote Yale Law School professor and China commentator Taisu Zhang.

“Please don’t ever tell me again that Chinese politics is a meritocracy, at least in the conventional sense of the word.”

The grand unveiling sparked turmoil in Chinese stock markets on Monday, with investors fearing the new leadership team was a signal that Beijing was pivoting towards military and state power rather than business-friendly policies.

“[It shows there is no longer a] plausible faction of top officials representing different interests or ideas,” China expert Christopher Beddor from Beijing-based research group Gavekal Dragonomics told the Financial Times.

After delaying the release of its data last week, China on Monday announced that its economy grew 3.9 per cent year-on-year in the third quarter.

China had been expected to announce some of its weakest quarterly growth figures since 2020, with the world’s second-biggest economy hobbled by Covid restrictions and a real estate crisis.

Investors instead focused on the political developments, which raised fears Xi and his allies would continue with gruelling virus lockdowns and other policies that have punished the economy.

“There is no clear sign of a significant easing of the zero-Covid strategy,” Ting Lu, chief China economist at finance company Nomura said, noting that, if anything, the opposite had happened.

In a speech to close the Congress on Saturday, Xi insisted China’s Covid response has been a success.

Notably, Xi’s new number two, Li Qiang, is the top party official in Shanghai who was responsible for the brutal Covid lockdowns earlier this year that saw tens of millions of residents struggling to access food and medical care.

Sociology professor Yang Zhang from American University’s School of International Service in Washington D.C. said the unveiling of the new politburo was “the making of an All Xi’s Men team, the breaking of decade-long rules, and the birth of an unlimited supreme leader”.

“These are not entirely surprising, but Xi’s grab of power is still beyond our expectation. He is now a truly modern emperor,” Prof Zhang wrote.

“Xi will rule China for not one but at least two and likely three terms (15 years). He is ‘only’ 69 [years] old: Mao ruled China until his death at 83 and Deng kept CMC [Central Military Commission] Chair until 1989 when he was 85. So don’t expect Xi to retire before 2037. Xi’s power apex just started, today.”

Prof Zhang noted that Li’s promotion to Premier was “not only unprecedented but also showcases to everyone that loyalty, rather than popularity, is the key for your promotion”.

“The disaster of Shanghai lockdown did not stop Li’s elevation precisely because he followed Xi’s order despite all criticism,” he wrote.

Yale Law School’s Prof Zhang argued the “emperor” analogies did not go far enough.

“Most Chinese emperors neither held unchecked power, nor lacked a succession plan,” he said.

“Prior to the Qing [dynasty], bureaucrats imposed considerable checks on the emperor’s power, so much so, in fact, that it bogged down the state more often than not. During the Qing, Manchu emperors gained more control over the state, but the state’s control over society at large shrunk dramatically, and local self-governance was the norm. In either era, there were usually institutionalised succession plans.”

Prof Zhang said China’s current political situation was not a “natural extension” of its imperial history.

“In fact, we’ve almost never had anything like this in the imperial past,” he said.

“As a rule, one should never draw a straight line between a pre-modern state that lacked coercive powers over local communities and a modern state that wields enormous control over individual activities – arguably more control than any other state in human history.”

The 20th Communist Party Congress also laid bare the striking gender imbalance in the upper echelons of Chinese politics, with not a single woman making the 24-person politburo for the first time in at least a quarter of a century.

As Xi and his allies concentrated power over the weekend, the party’s highest-ranking female leader retired.

Veteran politician Sun Chunlan, a vice premier overseeing China’s health policies, was absent from the Central Committee list published on Saturday, meaning she has stepped down.

In the world’s biggest political party – which counts 96 million active members – women have never held much power, and now hold even less.

Sun, 72, was the only woman in the former politburo, the party’s executive decision-making body.

Often dispatched to inspect Chinese cities in the grip of surging Covid-19 outbreaks, the former party chief of Fujian province and Tianjin municipality became the public face of the zero-Covid policy, commanding tough measures wherever she went, prompting the nickname “Iron Lady”.

“The Chinese Communist Party’s commitment to women’s rights I think is more like a commitment to advance women’s economic rights,” said Minglu Chen, a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney.

“It’s really about, ‘Women should join the paid labour force.’”

The men who rule China

Xi Jinping

The 69-year-old was re-elected as general secretary of the Communist Party, paving the way for him to secure a third term as Chinese President at the government’s annual legislative sessions next March.

Xi abolished the presidential two-term limit in 2018, paving the way for him to govern indefinitely.

He has consolidated power since becoming general secretary in 2012, partly through a wide-ranging anti-corruption campaign that brought down his political rivals.

This means that “elite promotions are less of a balancing act between rival factions and more of a loyalty contest within Xi’s dominant faction,” Neil Thomas, senior China analyst at Eurasia Group, said.

Li Qiang

The former Shanghai party chief and Xi confidant was promoted to number two in the party hierarchy, making him likely to be named premier at next March’s legislative sessions.

It would be an unusual appointment since Li, unlike most past premiers, does not have experience as a vice premier managing central government portfolios.

The 63-year-old rising star’s prospects were seemingly in doubt after he bungled a harsh two-month lockdown of Shanghai earlier this year that saw residents left with a lack of access to food and medical care.

Li is viewed as one of Xi’s favourites, having served as the leader’s chief of staff while he was party boss of the affluent Zhejiang province between 2004 and 2007.

Zhao Leji

The 65-year-old former head of the party’s top anti-corruption watchdog has remained on the Standing Committee, being promoted to number three in the party hierarchy.

The experienced administrator has been party secretary of two provinces and a politburo member since 2012.

Wang Huning

Xi’s ideology tsar and existing Standing Committee member has been promoted to number four in the party line-up.

Dubbed the “brains behind the throne”, the 67-year-old former university professor has devised ideologies for three current and former Chinese presidents, and is the architect of Xi’s “China Dream” slogan, as well as the country’s more assertive foreign policy.

In one of his most famous works, “America Against America”, he argued for the US’ inevitable downfall due to wayward cultural values like decadence and individualism.

Cai Qi

Current Beijing party chief Cai Qi has been promoted to the Standing Committee and becomes the head of the General Secretariat, managing the day-to-day affairs of the party, according to a member list released by Xinhua.

The 66-year-old is seen as a close political ally of Xi due to his time working under him in the provinces of Zhejiang and Fujian.

He was sent to Beijing as deputy head of the General Office of the National Security Commission in 2014, before becoming Beijing party boss in 2017. He oversaw the successful Beijing Winter Olympics in February.

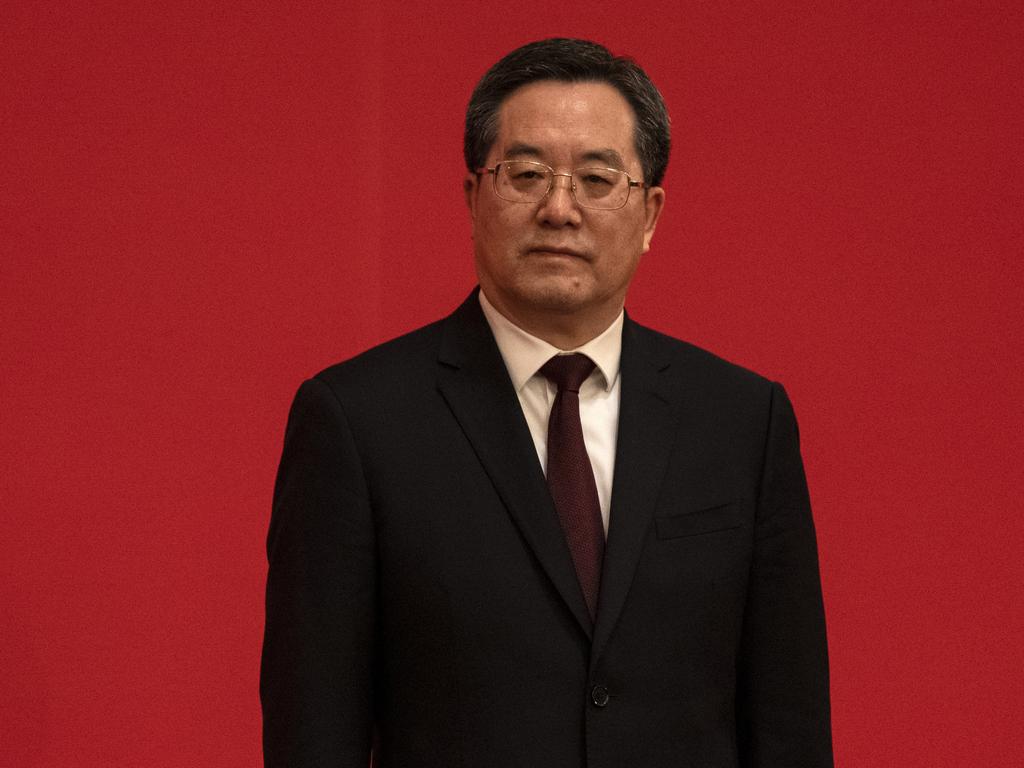

Ding Xuexiang

The low-key politburo member and top aide of Xi has been promoted to the Standing Committee – an appointment widely expected by analysts for a member of the leader’s inner circle.

The 60-year-old regularly accompanies Xi on official engagements, becoming a familiar face hovering in the background of state media reports, never far from his boss.

The former head of the Communist Party’s General Office has never served as a provincial-level party boss or governor, making his appointment effectively a reward for his loyalty to Xi.

The pair became close while Ding served in the Shanghai party committee – Xi was Shanghai’s top party boss in 2007-8 – and he moved to Beijing to work as Xi’s personal secretary in 2013.

“If Xi’s two secretaries lead the [government] State Council … it will no longer be parallel with the Party, but simply one [of] many institutions under the leadership of the Party, and of Xi,” tweeted American University’s Prof Zhang.

Li Xi

The current politburo member and party chief of economic powerhouse Guangdong province has been promoted to the Standing Committee, in an appointment widely anticipated by observers.

Li, 66, was confirmed as head of the powerful Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the party’s powerful anti-graft watchdog, in a list released by Xinhua.

Li is regarded as a confidant of Xi, having known him since the 1980s after working as secretary for a close ally of Xi’s father, revolutionary leader Xi Zhongxun. He also built up a power base in Shaanxi, Xi’s ancestral province.