Why the Australian housing market is finally ready to crash

After house prices rose by 22 per cent last year, Australia’s property market is running out of steam. And one thing could see prices crash.

After rising a whopping 22 per cent in 2021 – the strongest annual growth since 1989 – Australia’s house price boom is fast running out of steam.

Price growth across Australia’s two largest and most unaffordable housing markets – Sydney and Melbourne – has slowed to a crawl, rising only 0.40 per cent and 0.25 per cent respectively so far in 2022.

This slowing momentum across our two biggest cities has, in turn, pulled down national dwelling value growth, despite smaller markets like Brisbane and Adelaide continuing to run strong.

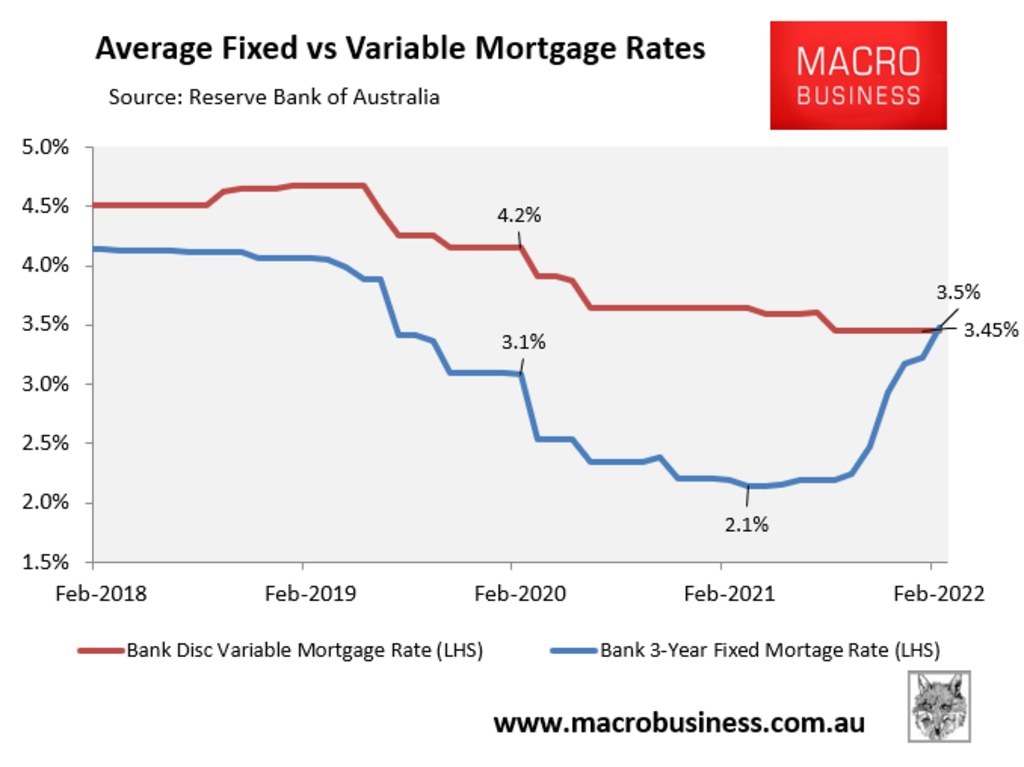

Fixed mortgage rates on the rise

One of the key drivers behind the slowing house price momentum is rising mortgage rates.

Although the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has kept the official cash rate on hold at a rock bottom 0.1 per cent, in turn keeping variable mortgage rates at their current record low levels, fixed mortgage rates have crept higher in response to the RBA tapering its quantitative easing program.

For example, the average owner-occupier 3-year fixed rate mortgage was only 2.1 per cent a year ago. Now average rates on these same mortgages have risen to 3.5 per cent, according to the RBA.

Investor mortgages have experienced similar increases.

Markets are tipping massive interest rate increases

According to the latest financial market forecast, the RBA will begin lifting the official cash rate in June 2022, with the cash rate to rise by 2.15 per cent by June 2023.

That is the equivalent of nine interest rate hikes in only 12 months. It would also represent the fastest pace of increase anywhere in the world.

It is fair to say that if the RBA was to increase the cash rate in line with the market’s forecast, then Australian house prices would crash.

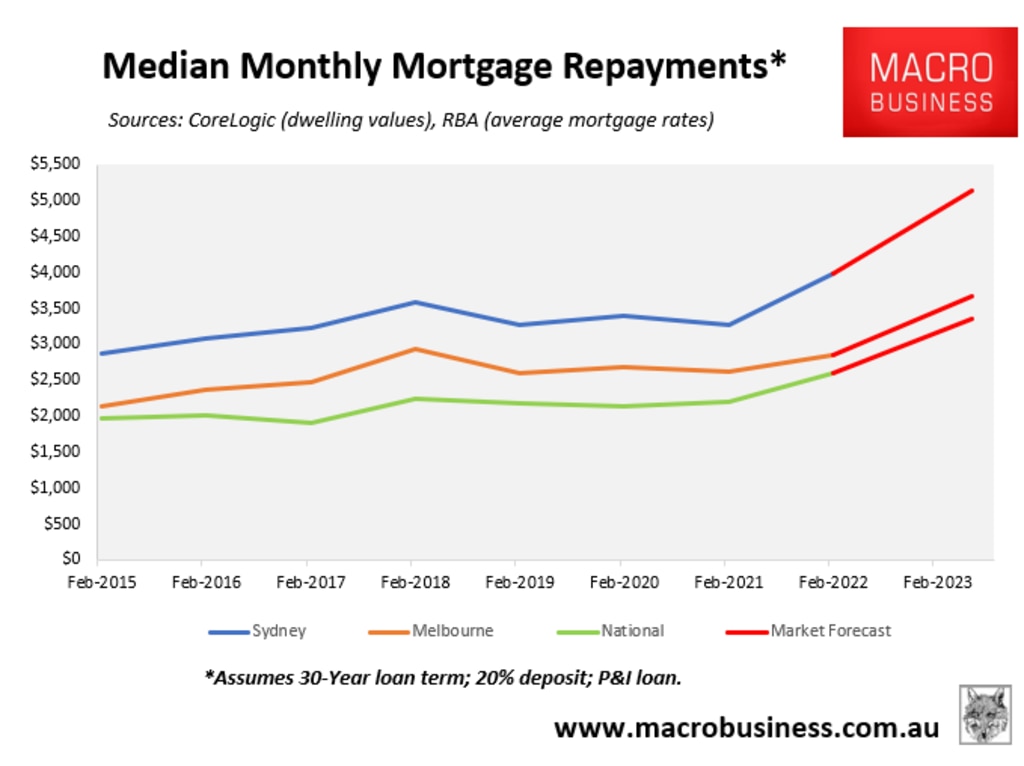

To illustrate why, consider the next chart showing the average monthly repayment on the median priced dwelling across Sydney, Melbourne and nationally, assuming a 30-year principal and interest mortgage and a 20 per cent deposit:

If the discount variable mortgage rate was to rise by 2.15 per cent to 5.60 per cent, as predicted by the market, then mortgage repayments would lift by 29 per cent from their current level.

This would see monthly mortgage repayments on the median priced Australian home rise from $2599 in February 2022 to $3344 – an increase of $744.

For the median Sydney buyer, median monthly repayments would rise by a whopping $1141, whereas they would rise by $818 in Melbourne.

The impact would be even more severe for the circa $500 billion worth of fixed rate mortgages due to expire over the next two years, most of which were originated at rates under 2.5 per cent. Those borrowers are facing more than a doubling of mortgage rates when it comes time to refinance.

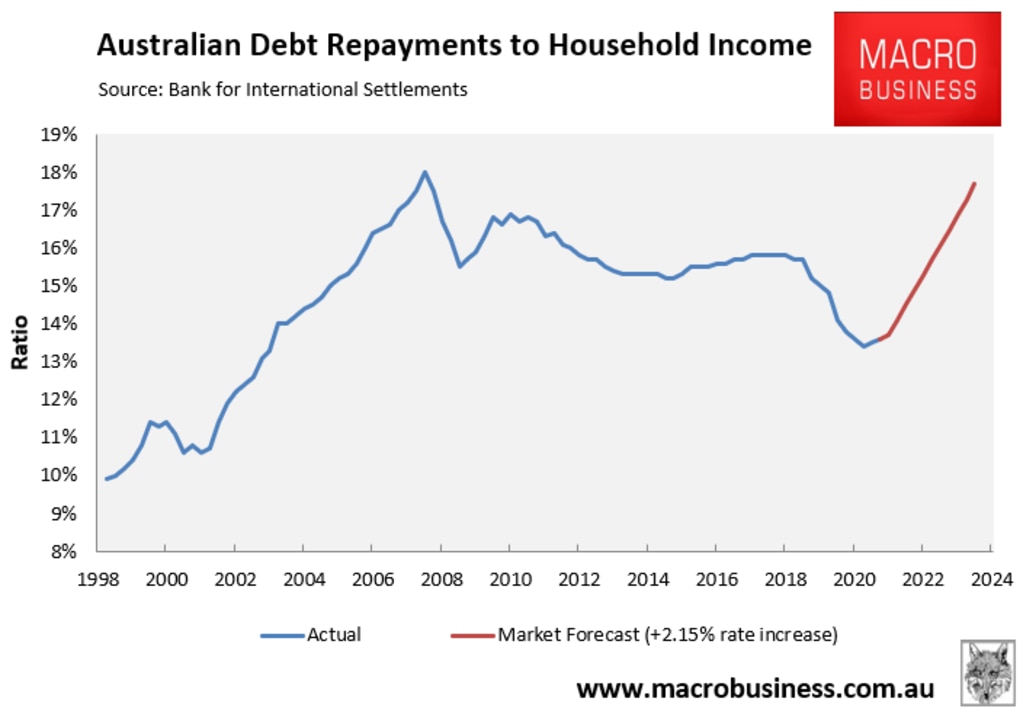

Indeed, a 29 per cent increase in monthly mortgage repayments would lift Australia’s Debt Servicing Ratio – defined as the percentage of household disposable income going towards principal and interest debt repayments – to its highest level since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008:

The market is wrong

Just because the market is predicting sharp interest rate hikes doesn't mean it will come true.

The lever is in the hands of the RBA, not the markets. And the RBA has repeatedly suggested that it is in no rush to lift rates and will keep them on hold until annual wage growth rises above 3 per cent (from 2.3 per cent currently).

My prediction is that the first rate hike won't arrive until late this year. The tightening cycle will also be far shallower – i.e. circa 1 per cent – because Australian households are so indebted and sensitive to small rate rises.

There is also a decent chance that the Russian-Ukraine War will tip the global economy into recession, in which case the RBA might respond with further monetary stimulus rather than tightening.

Whatever the case, the market’s interest rate projections are far too heroic and detached from reality.

Such a sharp increase in mortgage repayments would crash the housing market and economy, which is exactly why the RBA won‘t raise rates nearly as early, swiftly nor far as the market is predicting.

Leith van Onselen is Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.