Proof Australia’s property boom is over as house prices slow rapidly

House prices in capital cities are slowing at a rate not seen in more than 30 years, signalling the property boom is finally coming to an end.

Australia’s property boom may finally be coming to an end, with house prices across the country slowing at a rate not seen in decades.

Uuntil now, Australian homeowners have had the upper hand, with the property market enjoying unprecedented levels of growth year-on-year, increasing by 35 per cent since mid-2020.

However, a report from REA Group’s PropTrack found that is all coming to an end, with national house prices falling by 0.11 per cent in May and 0.15 per cent across all capital cities.

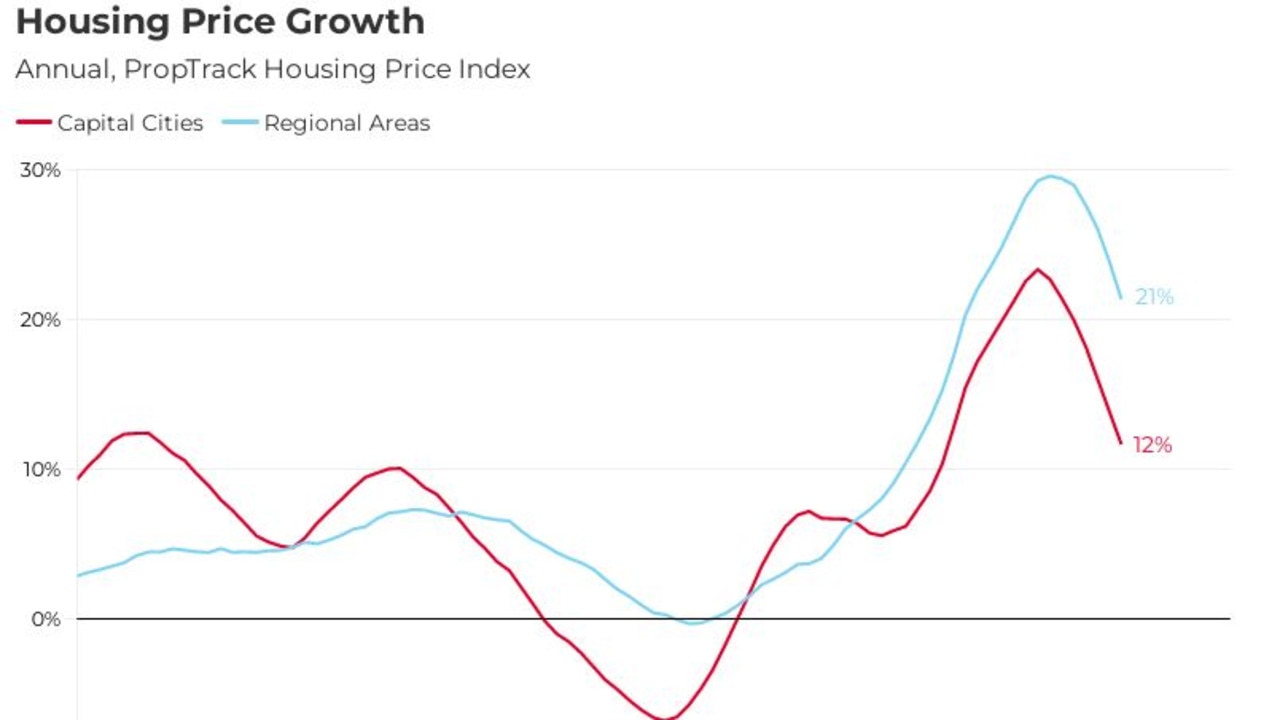

Annual price growth has fallen from 24 per cent just six months ago to 14 per cent now.

Several banks have now forecast price drops of between five and 15 per cent through to the end of 2023. A 15 per cent drop in the median property price would see the value of the average property falling by $150,000.

The last time house prices slowed this quickly was more than 30 years ago – at a time when Australia was heading into a recession.

It doesn’t bode well for the current situation, with PropTrack economist and report author Paul Ryan saying monthly prices have slowed just about everywhere, with growth also stalled in regional areas.

“Prices were flat in regional areas in May which represents a sharp slowdown and the slowest monthly result in regional Australia since May 2019,” Mr Ryan said in the report.

Concerned about falling house prices? Check out Compare Money's guide >

“Nevertheless, regional areas continue to outperform capital cities and have benefited from relative affordability and preference shifts towards lifestyle locations and larger homes following the pandemic.

“Prices have increased 21 per cent in the past year in regional areas, but only 12 per cent in the capitals,” he said.

Prices have continued to decline in Sydney and Melbourne, dropping by 0.29 and 0.27 per cent respectively.

The only capital cities managing to buck the trend have been Brisbane and Adelaide, which have continued to benefit from affordability and pandemic-induced preference shifts.

Brisbane saw a monthly growth of 0.35 per cent, while Adelaide prices shot up by 0.58 per cent.

Houses are continuing to outperform units, with many Australians favouring more space since the start of the pandemic.

In the capital cities, peripheral areas have increased in prominence over the post-pandemic period as people continue to work from home and the need for a short commute time reduces.

It is possible, however, this trend could swing back towards inner cities as more workers begin to return to the office and immigration returns in 2022 and 2023.

Mr Ryan noted that a clear “two-speed housing market” is continuing.

Affordable, lifestyle regions of Brisbane, Adelaide, regional NSW, Queensland and Tasmania are seeing solid growth, while prices everywhere else are either flat or falling.

“As inflation built in early 2022, expectations interest rates would move higher has weighed on price growth,” Mr Ryan said.

“The RBA moved to increase official interest rates for the first time more than a decade in early May, with substantially higher borrowing costs expected at the end of the year.

“Buyers now expect the affordability of current prices to further erode.”

On Tuesday, the RBA decided to lift the official cash rate by 50 basis points, to 0.85 per cent, returning it to its highest level since September 2019 and marking the first back-to-back rate rise in 12 years.

The unexpected size of the rate rise has sent shockwaves across the country, and provided yet more evidence that all is not well economically.

And clues from the RBA itself – as well as predictions from countless finance experts – indicate yesterday’s hike will be the tip of the iceberg.

News.com.au spoke to Mr Ryan in the wake of Tuesday’s hike, with the economist revealing what this development means for property prices.

“We’re likely to see continued slow growth in housing prices as the cash rate increases,” Mr Ryan said. But he admitted it was difficult to predict exactly when and how much it will affect the market.

“It normally takes a little while for interest rate rises to start to affect [house] prices.

“I think, while it’s correlated, it’s more coincidental that we saw these first housing price falls in May, right after the RBA raised rates for the first time in over a decade.”

He said the price slump was caused less by the RBA’s decision and more as a side effect of inflationary pressures and buyers growing more cautious in anticipation of a rate rise which caused a “dramatic slowdown in growth that has culminated in a fall”.