‘All-time high’: Real reason you can’t find a house revealed

Australia is in the grip of a full-blown housing crisis – and a new set of data has revealed exactly what’s driving the depressing trend.

As the clock continues to tick down until the next federal election, the issue of housing remains at the forefront as one of the major political battlegrounds that could decide who wins government and under what sort of circumstances.

But amid the ongoing debate, there is a more abstract issue that is instrumental in determining what level of population growth is viable and how much dwelling stock needs to grow in order to keep up with demand, demographics or more accurately, household sizes.

In short, as the average size of a household decreases, more homes are required.

Conversely, as household sizes rise, fewer homes are required.

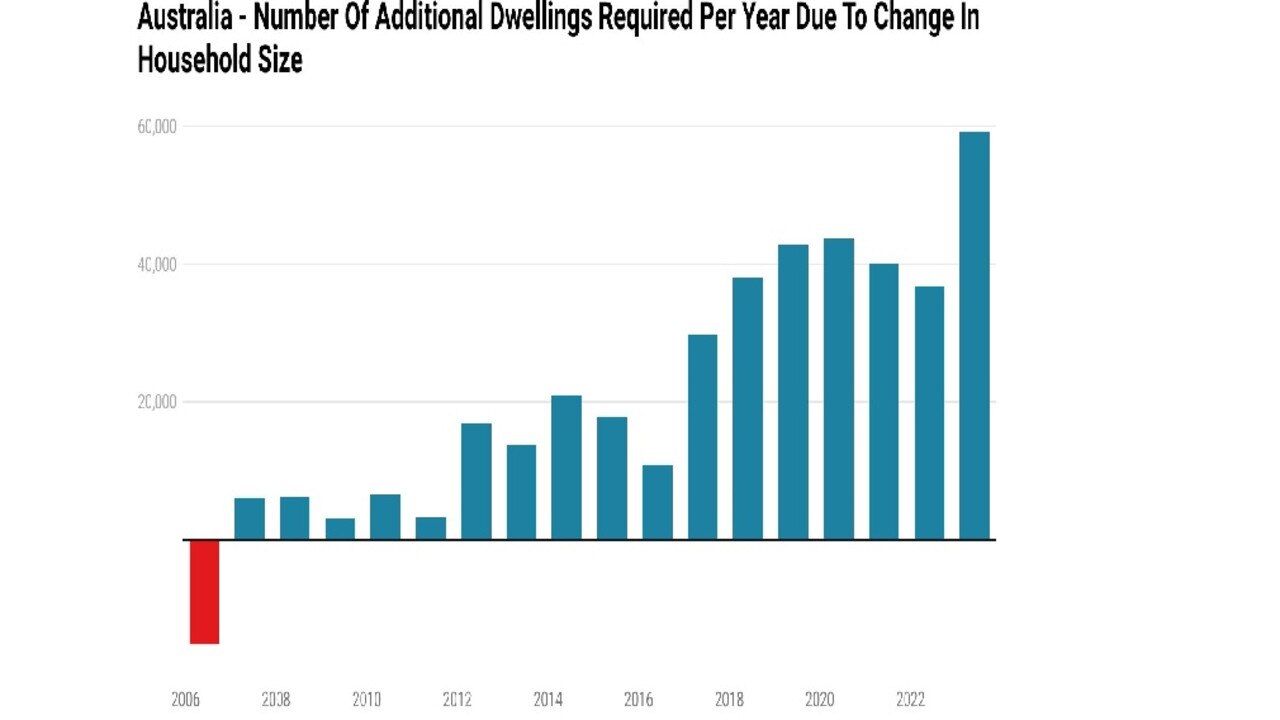

Based on the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimates of the change of the average household size in the last 12 months of data, this change added demand for more than 59,000 additional homes or 34 per cent of all dwelling completions that occurred over the same period.

This factor hasn’t always been a major contributor to housing demand.

During 2005-2006, household sizes actually rose, reducing demand for homes by more than 15,000. More recently, as late as 2010-2011, the increase in household size demanded just 3300 additional homes.

But as some households became more affluent, the population aged, had fewer children and more people chose to live alone, household sizes continued to fall – and this had a greater and greater impact on housing demand.

In the last data point prior to the impact of the pandemic which covers 2018-2019, an additional 42,800 homes were required based solely on this factor.

Changing tides and challenging conditions

When looking at a series of charts quantifying the underlying conditions such as working age population growth, dwelling completions and interest rates, it swiftly becomes clear that this additional shift higher in housing demand could scarcely have come at a worse time.

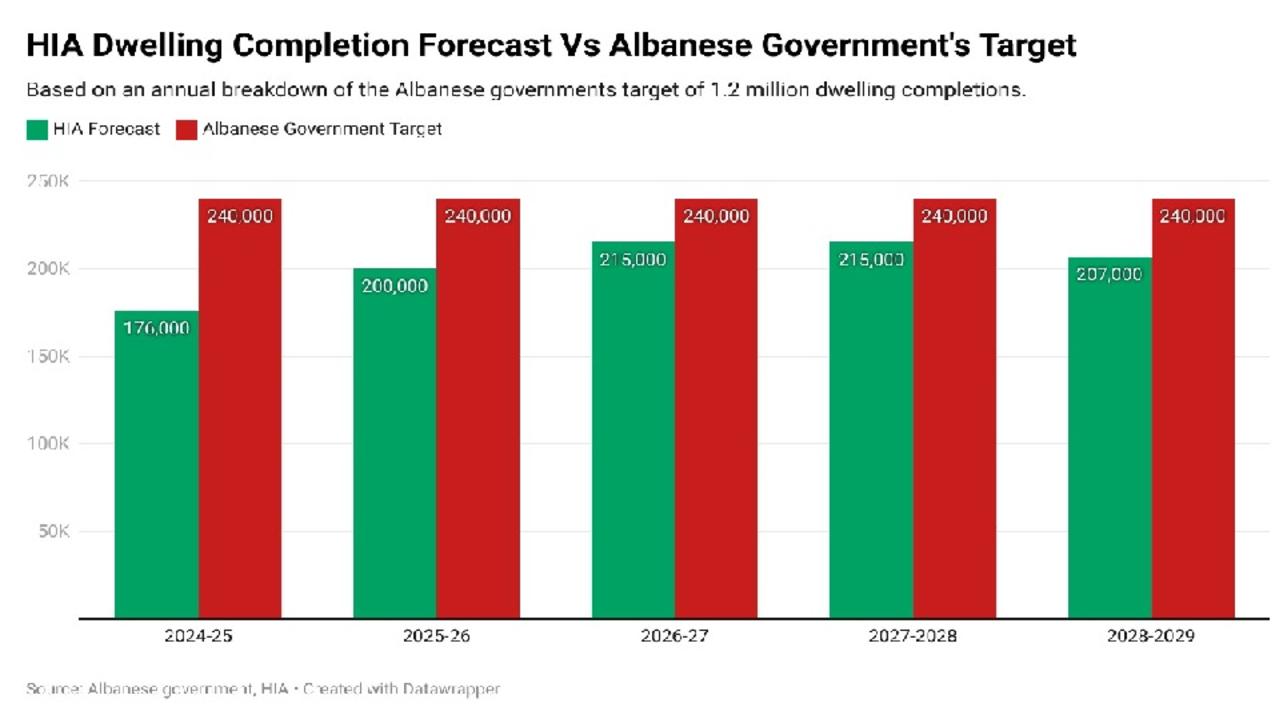

Dwelling completions are not expected to bottom until the fourth quarter of this year and when they do pick up, they are tipped by the Housing Industry Association (HIA) and others to come in well short of the 240,000 homes per year target laid out by the Albanese government.

If we assume that the demand from falling household size runs at roughly the same average rate as it has in the last five years, going forward, an additional 44,500 homes per year will be required on top of those demanded by migration and natural population growth.

HIA chief economist Tim Reardon recently estimated that if population growth ran at 400,000 per year for 2024-25, which is roughly in the ballpark of where it’s expected to land during that period, the nation will need to build at least 230,000 homes to meet underlying demand, based on the economy continuing to grow at a relatively slow rate.

Not set in stone

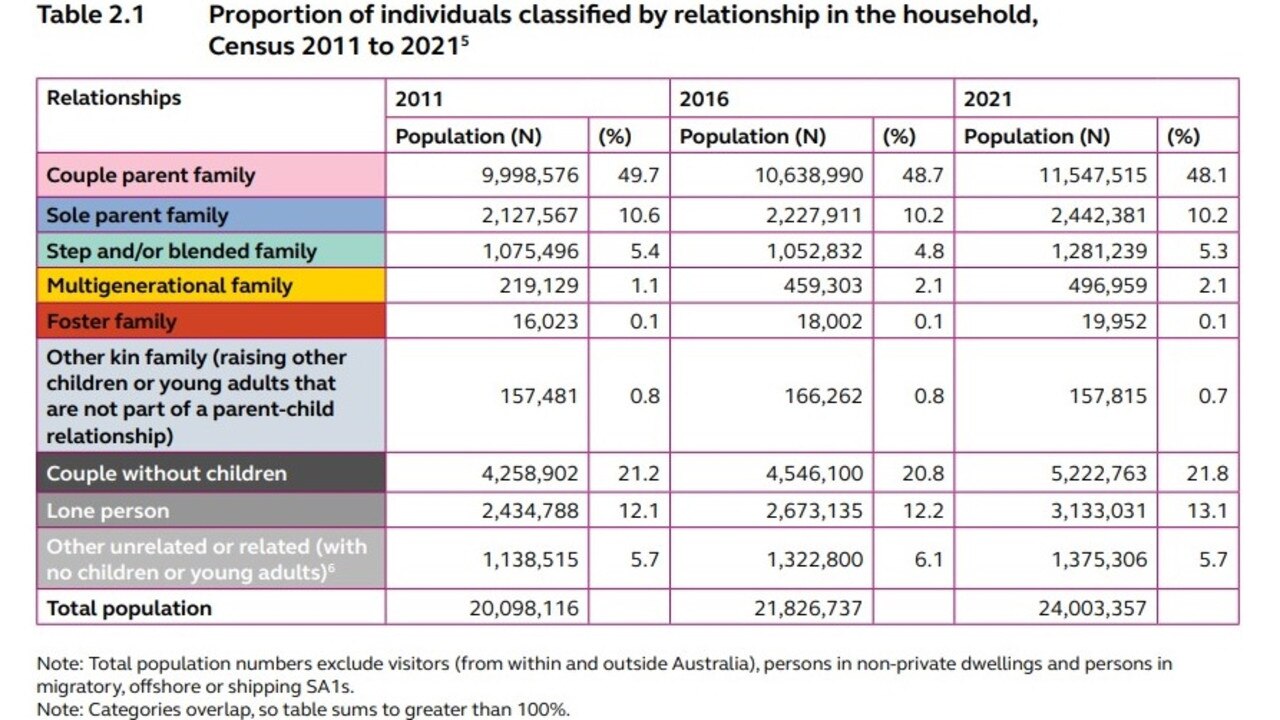

It is said that demographics are destiny and that much is arguably true, but what is not set in stone is the impact of these changes on household sizes. In theory, if enough Australians were driven to create a multigenerational household, share house or otherwise cohabitate with a larger number of people, then the impact of changing demographics could be offset, at least somewhat.

However, despite the rental crisis being a factor to varying degrees across two years of household size data, there is not yet evidence to suggest that the trend of more Australians cohabitating has been able to adequately offset the demand stemming from the drive for smaller household sizes.

This is not to say there isn’t data to suggest that sharehousing and other forms of cohabitation aren’t on the rise. There is census data showing more and more young Australians are staying at home for longer, and multigenerational households have been rising for more than a decade.

In terms of a more recent time horizon, data earlier this year from sharehousing website Flatmates.com.au revealed demand hit an all-time high, with a record number of users searching out either a flat mate or an existing sharehouse.

The outlook

As things stand, despite the rental crisis, a lack of affordable housing and the ongoing trend toward multigenerational living and adult children staying at home, it appears that the demographic tide is the greater force acting on housing demand.

While new data and shifts in living arrangements driven by circumstance could change this outlook, based on current trends, roughly an additional 45,000 homes per year will be demanded by decreasing household sizes. This will significantly impact what level of population growth is viable in terms of building enough homes to meet demand.

Ultimately, it’s up to policymakers to ensure that the settings of the migration system, the economy and the construction sector are all working in unison toward the goals held by our society.

Which is, in short, enough homes – in particular freestanding houses – so that more Australians can live the way they choose to.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator