What’s going on with Aussie wages – and where are they going?

New figures have revealed Australia is bucking a major global trend for all the wrong reasons. And it’s bad news for most workers.

The recent release of the latest wage growth figures confirmed what many Australians already felt – relative to inflation, they were once again going backwards.

After making some progress between the March and December quarter of last year, since then real wages have again gone backwards as they did from June 2020 to March 2023.

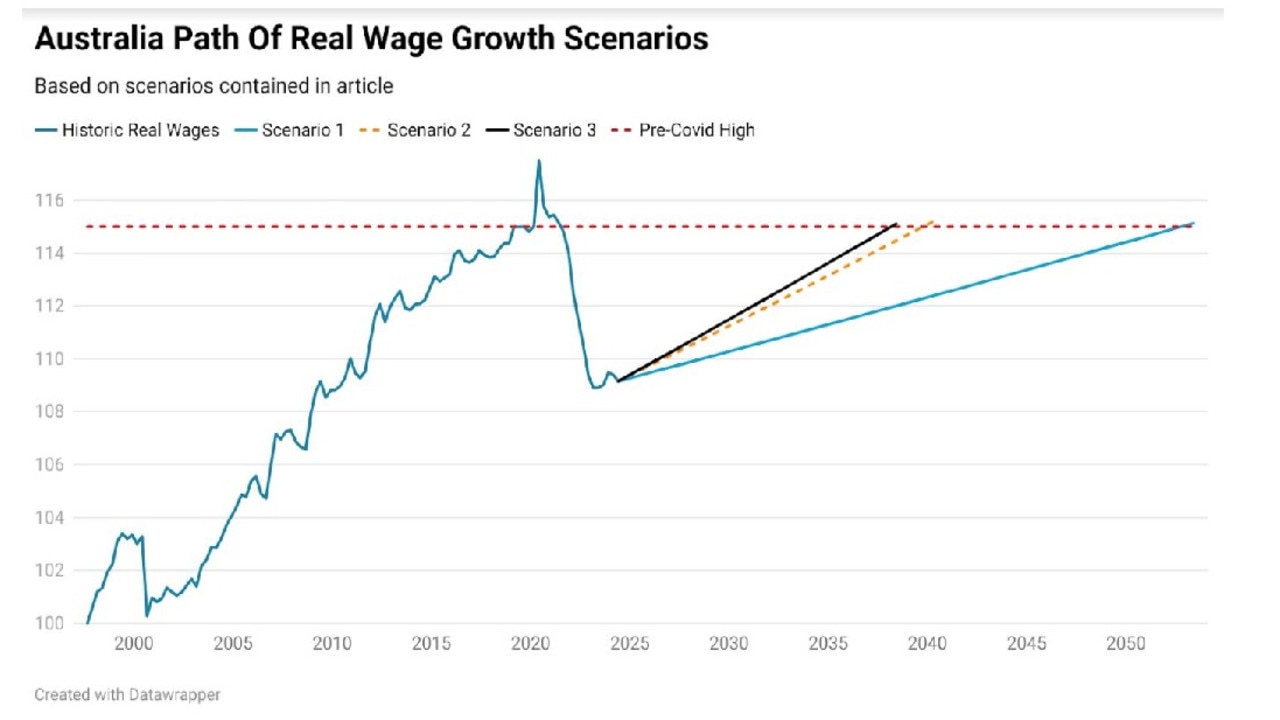

Currently real wages sit 5.1 per cent below the pre-Covid peak which was recorded in the September quarter of 2019 and 7.1 per cent below the peak recorded in the early months of the pandemic, as distortions created by lockdown and the exodus of temporary visa holders from the workforce sent wages artificially higher.

In terms of where real wages currently sit compared to past performance, as of the end of the June quarter of 2024, they sat at almost exactly the same level as they did in the June quarter of 2009.

All in all, since bottoming out, real wages have grown by a cumulative total of 0.23 per cent.

Headline

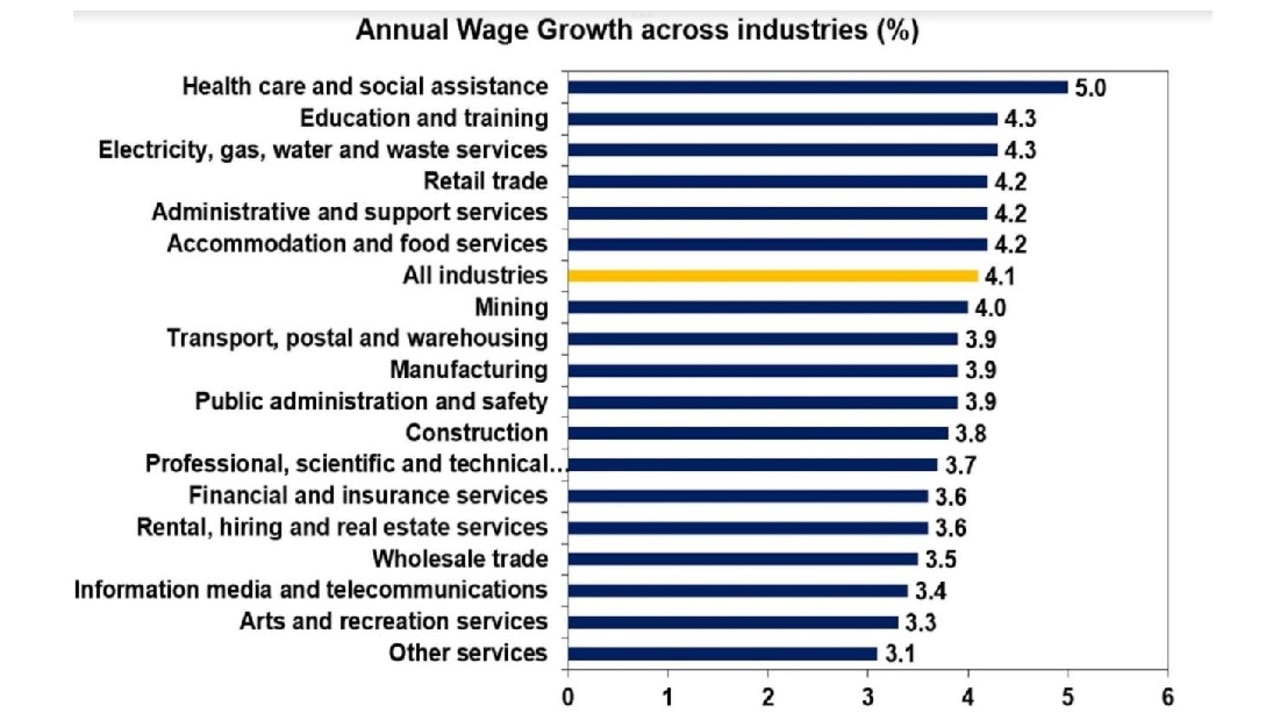

As of the latest data, wages grew by 0.8 per cent in the last quarter and 4.1 per cent over the last year. The annual figure is currently being heavily supported by the performance during the September quarter of 2023, during which a historically large increase to minimum and award wages saw wages rise by 1.2 per cent during the quarter.

While the September quarter of this year is likely to bring another round of relatively strong increases to minimum and award wages, at least when compared with what had become the norm prior to the pandemic, the expectation of economists and the Reserve Bank is that the peak of wages growth is in the rear view mirror.

In their latest forecasts released earlier this month, the RBA projected that wages growth would moderate to 3.6 per cent by the end of the year and still remain at a relatively robust 3.4 per cent out to the June quarter of 2026.

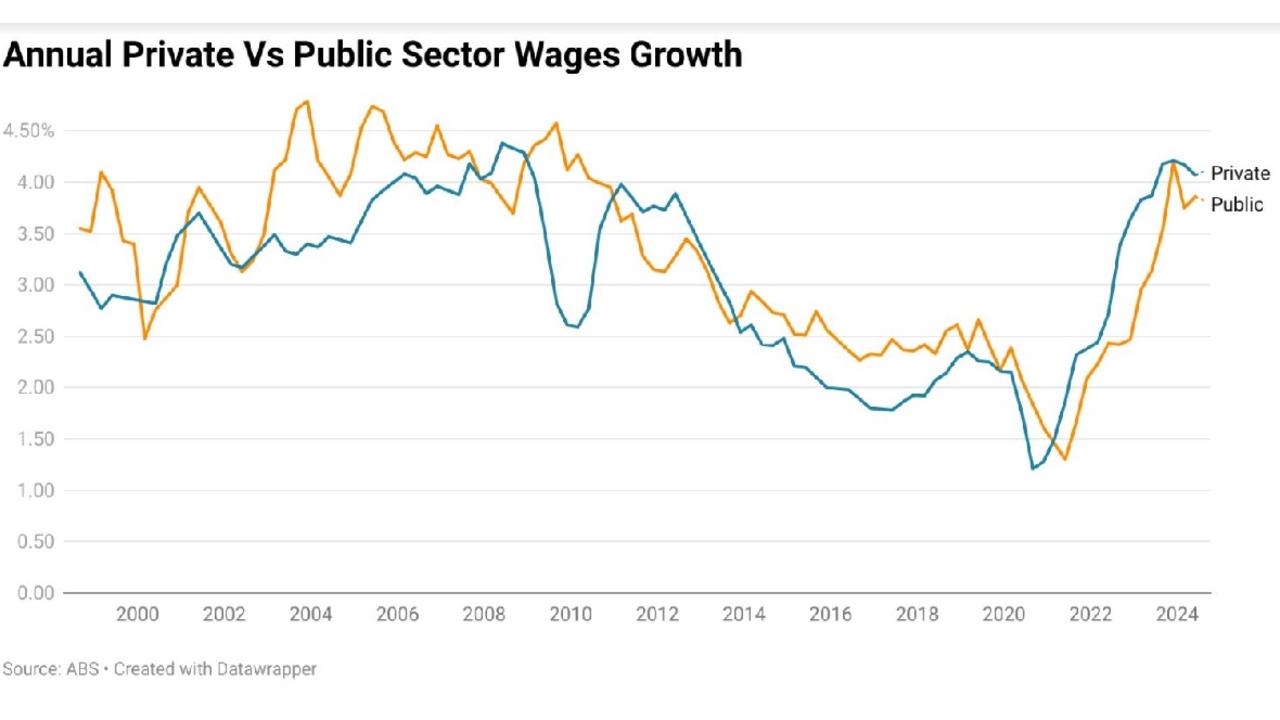

It’s worth noting that traditionally this is where Australian wages growth sees a major divergence between private and public sector wage growth. Private sector wage growth tends to peak first, while public sector wage growth generally peaks later in the economic cycle.

Wages by industry

As one might expect, the performance of wages across various different industries varied significantly. At the top end of things, healthcare and social wages were up 5.0 per cent, education and training up 4.3 per cent and utility services up 4.3 per cent.

At the other end of the spectrum, other services wages were up 3.1 per cent, arts and recreation up 3.3 per cent and information technology and communication up 3.4 per cent.

A deep hole

After seeing the purchasing power of the average pay packet decline by up to 5.1 per cent compared with the pre-Covid peak in real wages, this raises a challenging question – how long is it going to take to gain back what has been lost?

In order to get a handle on some of the possibilities, we’ll look at three different scenarios which have quite a different set of assumptions.

Scenario 1: Real wage growth continues at the same rate as it has since bottoming in March 2023.

Scenario 2: Real wages grow at the average rate seen in the three years prior to the pandemic.

Scenario 3: Real wages grow in line with the average rate present in the forecast estimates of the RBA, extrapolated out into the future.

In Scenario 1, real wages regain the pre-Covid peak in 2052, in Scenario 2, in 2039 and in Scenario 3, 2038. In short, without a major shot in the arm to change the calculus of the real wage growth settings of the economy, wage earners are going to be waiting for a long time to regain the purchasing power they have lost.

The outlook

As the RBA has showed with its wage growth forecasts coming in consistently far too optimistically for almost a decade, predicting wage growth outcomes can be a challenging task.

But of the lessons we can take away from the hard data, the news is not encouraging.

From the United States to Germany and across most of the developed world, wages growth has been much stronger in recent years than it was prior to the Global Financial Crisis. In this, Australia bucks the trend for all the wrong reasons.

Despite having largely closed international borders for almost two years, several instances of reversing net migration and by far the largest government and central bank stimulus in the history of the nation, wages growth topped out at just 4.2 per cent.

The fact that even under as close to ideal conditions wages growth still only got to within a stone’s throw of the highs recorded prior to the GFC speaks to a level of weakness in the wage growth prospects of the nation’s economy.

More Coverage

The reason for this weakness is a matter of debate for economists, with industrial relations settings, weak productivity growth and a plethora of other theories put forward to explain why wage growth settings are much weaker than they have been in the past.

Ultimately, these are the circumstances that we find ourselves in and if all else remains equal, the settings under which we continue our ascent to attempt to regain the purchasing power our collective wage packets had prior to the pandemic.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator