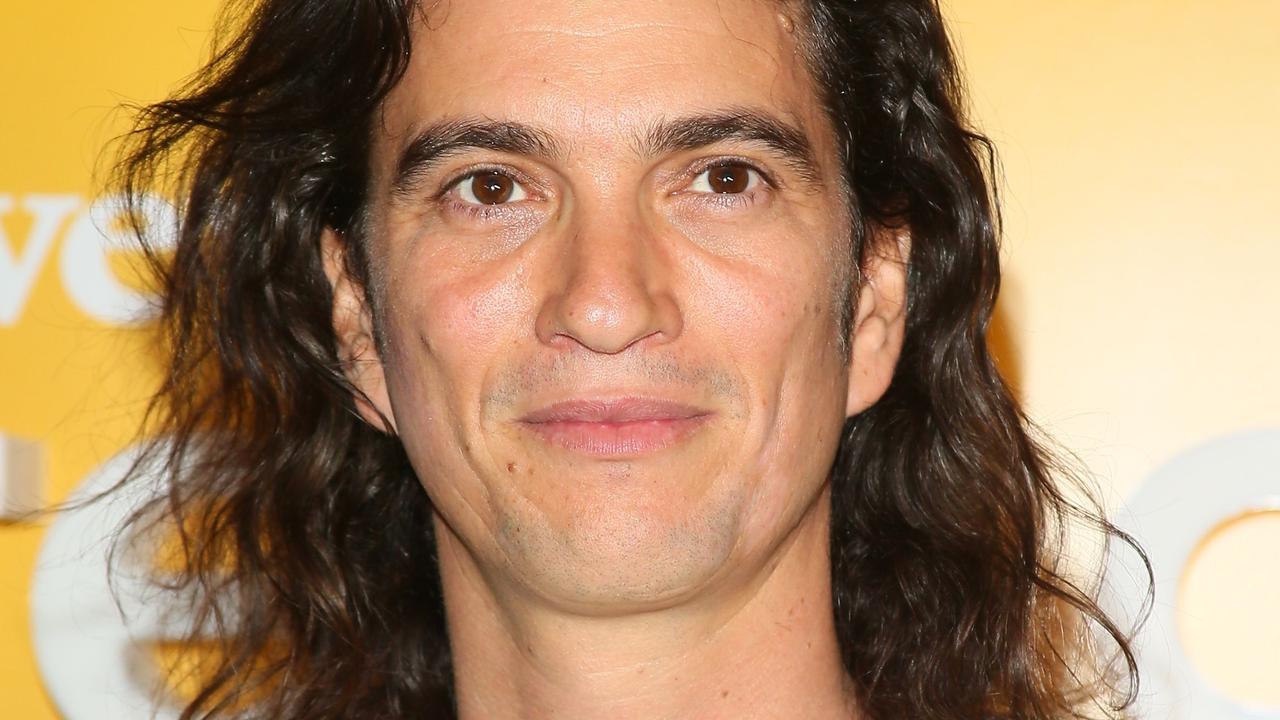

WeWork’s former CEO Adam Neumann gives first interview in two years, doesn’t apologise to dudded employees

His start-up company was once considered the next Uber. Two years on from its fall, thousands have lost their jobs – but Adam Neumann is richer.

Giving his first public interview in two years, the former CEO of WeWork, Adam Neumann, has said he has “multiple regrets” over how the business nearly collapsed under his direction.

The shared workspace company dismissed about two-thirds of its employees following a catastrophic initial public offering in 2019, which saw its valuation plunge from $US47 billion ($A64 billion) to $US7 billion ($U9 billion).

Given it previously employed more than 12,500 people according to public filings, that means more than 8000 of them lost their jobs.

But Mr Neumann didn’t suffer the same way. WeWork’s near-demise, and his own well-timed exit, left him over a billion dollars richer.

Speaking at The New York Time’s DealBook Online Summit on Tuesday, and breaking a long public silence, Mr Neumann was given multiple opportunities to apologise to those who’d lost their jobs. He expressed regret, but a direct apology was not forthcoming.

Stream more finance news live & on demand with Flash, Australia’s biggest news streaming service. New to Flash? Try 14 days free now >

“What do you say to all the employees – and we’re talking about thousands of employees who lost their jobs, whose (stock) options effectively became worthless – who look at you and say, not only did this all happen under your watch, but you walked away with more than a billion dollars?” asked CNBC journalist Andrew Sorkin.

Mr Neumann replied that he was “disappointed” for those employees, but added that when you “join a start-up, you take a risk”.

“Now, I wish it would have worked out differently for everybody, but the market now decided it’s worth $US9 billion (A$12 billion),” he said.

“It’s getting measured on a daily basis, and I actually think WeWork today has a better opportunity than it had then.”

In October 2019, just two months after the company filed its IPO paperwork which would allow it to become a publicly listed entity on the stock market, questions started to swirl regarding its profitability and leadership.

By October 22, it was announced Mr Neumann would step down as CEO, with WeWork's main investor SoftBank taking over.

On Tuesday, Mr Neumann said he understood the “perception” that he profited while his employees suffered, but dismissed it as a “false narrative”.

“This perception that as the company went from a $US47 billion ($A64 billion) valuation down to nine, and I profited somehow while the company was going down, is completely false.”

Mr Neumann said he received a $US180 million ($A243 million) “consulting non-compete fee” from SoftBank, along with $US870 million ($A1.2 billion) in stock sales on the private equity market. According to his own figures, then, he got over a billion US dollars, the equivalent of about $A1.4 billion.

From $64 billion to $12 billion: The rise and fall of WeWork

From 2014 to 2019, co-working company and New York start-up WeWork had been compared to the likes of Facebook, Uber and Airbnb, with Mr Neumann lapping up praise

WeWork held locations across every continent bar Antarctica and had created spin-off business for co-living (WeLive) and private education for kids aged 3-10 (WeGrow).

However, on the cusp of going public, WeWork’s IPO paperwork revealed the company had been built on a house of cards.

It was found that in 2018 WeWork had reported a $US2.1 billion drop in revenue, with losses spiralling since 2016.

Despite receiving a valuation of $US64.3 billion in January 2019, the company had actually squandered an eye-watering $US690 million in just the first six months of 2019 alone.

Two years later, on Tuesday, Mr Neumann admitted that his company’s rapid success “went to his head” and that mistakes were made.

“I have had a lot of time to think, and there have been multiple lessons and multiple regrets,” he said.

“It was never my intention not for the company to succeed.”

‘Entitled, top-down frat-boy culture’

Described as eccentric, disruptive and excessive, Mr Neumann’s leadership style also earned him many controversial headlines.

His excessive partying (during business hours), alleged drug-taking and spending has been well-documented. Ex-employees have alleged this permeated into WeWork’s culture.

(On Tuesday, the man himself said such claims “make good stories for movies and television shows”. He also defended his use of a private jet, saying people “focus on that so much” that they “miss the actual story”).

In 2018, the company’s former director of product management, Ruby Anaya accused the company of ignoring her complaints against male co-workers who touched her inappropriately, filing a lawsuit against WeWork at the Manhattan Supreme Court.

Court papers described obligatory happy hours, a work culture which encouraged binge drinking and allegations an employee grabbed her “in a sexual manner” at WeWork’s mandatory employment Summer Camp in 2017.

“The sexual harassment and assaults of (Anaya) did not happen in a vacuum,” they read, as reported by NBC.

“They are product in part of the entitled, frat-boy culture that permeates WeWork from the top down.”

Mr Neumann’s wife Rebekah – an actor, cousin of Gwyneth Paltrow and WeWork’s chief brand and impact officer – also had her own share of controversies.

Most notable were multiple reports she fired employees due to clashes with their energy.

Speaking to Bustle, a former employee said this was seemingly done randomly and “without obvious prejudice”.

“She was just a spoiled baby,” they said.

Two years on from his unceremonious ousting and the many controversies that followed, Mr Neumann is miraculously optimistic.

When asked if there was “one thing he wanted audiences to know”, he said: “In life, sometimes you are up and sometimes you are down.”

“When the times comes that you’re down … if you can learn a lesson from it and you can apply that lesson, it will be a great part of your journey and will become a good thing, not a tragedy.”

Oddly, it was the lack of being able to confront the truth that pushed his brand from start-up billionaire, to being described as the leader of a “$US20 billion start-up fuelled by Silicon Valley pixie dust”.