Donald Trump refuses to rule out use of military force to take control of Greenland and Panama Canal

Donald Trump has refused to rule out using the United States military to seize control of the Panama Canal and Greenland.

US president-elect Donald Trump has escalated threats against Canada, Greenland and Panama.

Mr Trump did not rule out military action to secure the Panama Canal, and he warned of economic retribution against neighbouring Canada, in a meandering press conference on Tuesday (local time), a day after Congress certified his election victory.

“I’m not going to commit to that,” Mr Trump responded, after being asked if he would rule out the use of military force to seize control of the Panama Canal and Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark.

The Republican president-elect had gathered reporters at his home in southern Florida to announce a $32 billion ($US20 billion) Emirati investment in US technology.

But his remarks quickly became a rally-style rant as he returned at length to familiar campaign themes.

“Since we won the election, the whole perception of the whole world is different. People from other countries have called me. They said, ‘Thank you, thank you,’” Mr Trump said as he set out his agenda for the coming four years.

The billionaire announced he was going to rename the Gulf of Mexico the “Gulf of America” and threatened the US’s southern neighbour again with massive tariffs if it does not halt illegal border crossings.

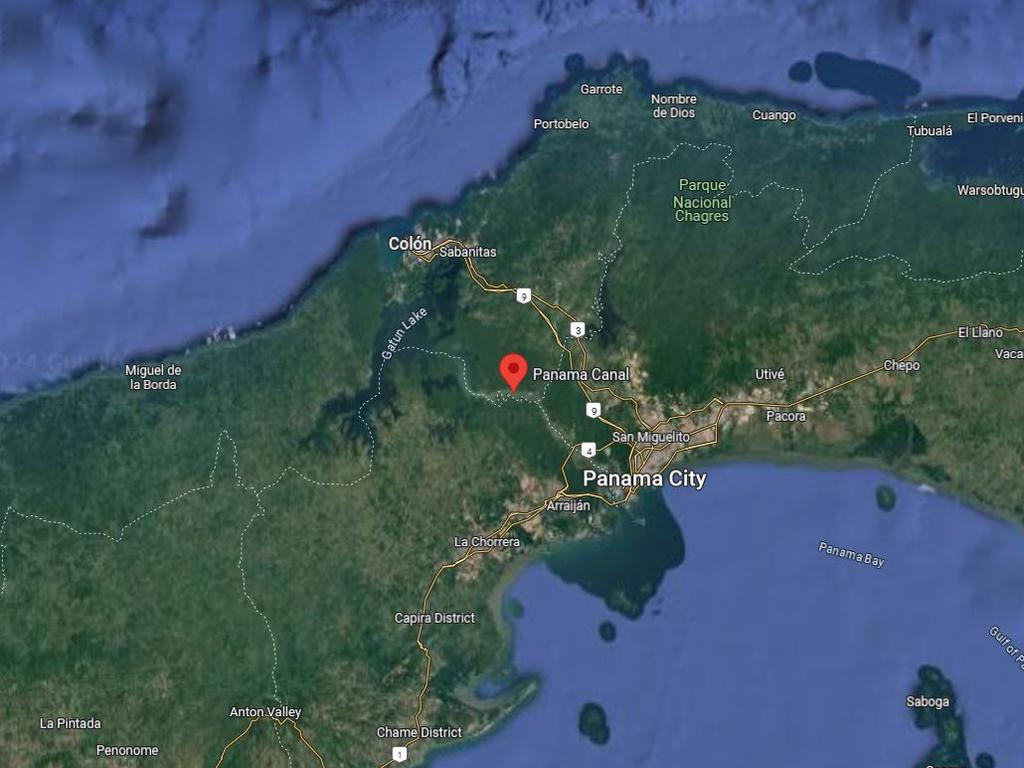

He refused to rule out using military force to seize Greenland and the Panama Canal — both of which he has long coveted. He has criticised recently-deceased Jimmy Carter for permitting a handover to local control of the Central American waterway when he was president.

Asked if he would use military force to bring Canada to heel, the incoming president said “no, economic force,” but added that eliminating the “artificially drawn” US-Canada border would be a boon to national security.

As with many of Mr Trump’s pronouncements, it was difficult to separate humour or bombast from genuine policy, but the remarks will be seen as an escalation of his rhetoric on territorial expansion and drew a dismissive response from across the border.

There is a “snowball’s chance in hell” that Canada will merge with the United States, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau responded, while Foreign Minister Melanie Joly said it would “never back down” over Mr Trump’s threats.

Donald Trump Jr’s private visit

Meanwhile, Donald Trump Jr made a private visit to Greenland on Tuesday, just weeks after his father restated his interest in the mineral- and oil-rich Danish autonomous territory, which itself wants independence.

The US President-elect on Monday called the Arctic island “an incredible place”, promising that its people would prosper should it ever be annexed by Washington.

“We will protect it, and cherish it, from a very vicious outside World. MAKE GREENLAND GREAT AGAIN!” he wrote on his Truth Social platform, after reiterating before Christmas that he wanted the United States to take control.

As Mr Trump’s son touched down on what he said was a day trip, Danish Prime Minister Mette Fredriksen warned: “Greenland belongs to the Greenlanders.” But Mr Trump Jr was at pains to point out he was not there “to buy Greenland”. “I will be talking to people. I’m just going there as a tourist,” he said on the social media platform Rumble.

Greenland holds major mineral and oil reserves — though oil and uranium exploration are banned — and has a strategic location in the Arctic, already home to a US military base.

Greenlandic media have said he would only be there for several hours and no official meetings were scheduled.

“This particular trip is probably just as Trump Jr said himself, to make video content,” Ulrik Pram Gad, a Greenland expert at the Danish Institute for International Studies, told AFP.

“What’s worrying is the way Trump (Sr) is talking about international relations, and it can be even worse if he starts ‘grabbing land’.”

Pushback

Mr Trump first said he wanted to buy Greenland in 2019 during his first term as president, an offer immediately quashed by Greenland and Denmark.

“Greenland is ours. We are not for sale and will never be for sale. We must not lose our long struggle for freedom,” Greenland’s Prime Minister Mute Egede said after Mr Trump’s Christmas message.

“Most Greenlanders will be in line with their prime minister that Greenland is not for sale but open for business,” Pram Gad said.

Aaja Chemnitz, a politician who represents Greenland in the Danish parliament, rejected Mr Trump’s offer with a firm “No thank you”.

“Unbelievable that some people can be so naive as to believe that our happiness lies in us becoming American citizens,” she wrote on Facebook, adding that she refused to be “a part of Mr Trump’s wet dreams of expanding his empire to include our country”.

With 57,000 inhabitants spread out across 2.2 million square kilometres (849,424 square miles), Greenland is geographically closer to the North American continent than to Europe.

Colonised by the Danes in the 18th century, it is located about 2,500 kilometres from Copenhagen, on which it depends for more than half of its public budget.

The subsidies it receives from Copenhagen amount to a fifth of its GDP. The other pillar of its economy is the fisheries industry.

Steps toward independence

Greenland has been autonomous since 1979 and has its own flag, language and institutions. But justice, monetary, defence and foreign affairs all remain under Danish control.

The creation of the post of Arctic ambassador has caused friction between Copenhagen and Nuuk, after Denmark two years ago appointed a diplomat with no ties to the region.

At the end of December, the Danish government announced Nuuk would from now on appoint candidates to the post, and represent the country on the Arctic Council.

In his New Year’s address, Greenland’s prime minister said the territory had to take “a step forward” and shape its own future, “notably when it comes to trading partners and the people with whom we should collaborate closely”.

In 2023, plans for a Greenlandic constitution were presented to the local parliament, the Inatsisartut.

However, “there has been no public debate on it so far,” researcher Ulrik Pram Gad said.

The issue could become a talking point during the upcoming campaign for Greenland’s legislative elections, which must be held before April 6.

“I expect there to be more talks about the formal steps towards independence, how politicians intend to secure the welfare state and the future of Greenland,” he said.