‘What gives?’: Why RBA is refusing to cut interest rates as inflation weakens

Inflation has “crashed” – but the RBA is still “misreading” the signals and leaving struggling Aussie homeowners in limbo. What gives?

ANALYSIS

For the last few months, most inflation reports in Australia have undershot the Reserve Bank’s expectations.

Inflation itself was weaker than expected. The Melbourne Institute’s monthly inflation leading indicator has crashed. The NAB business survey is back to normal prices.

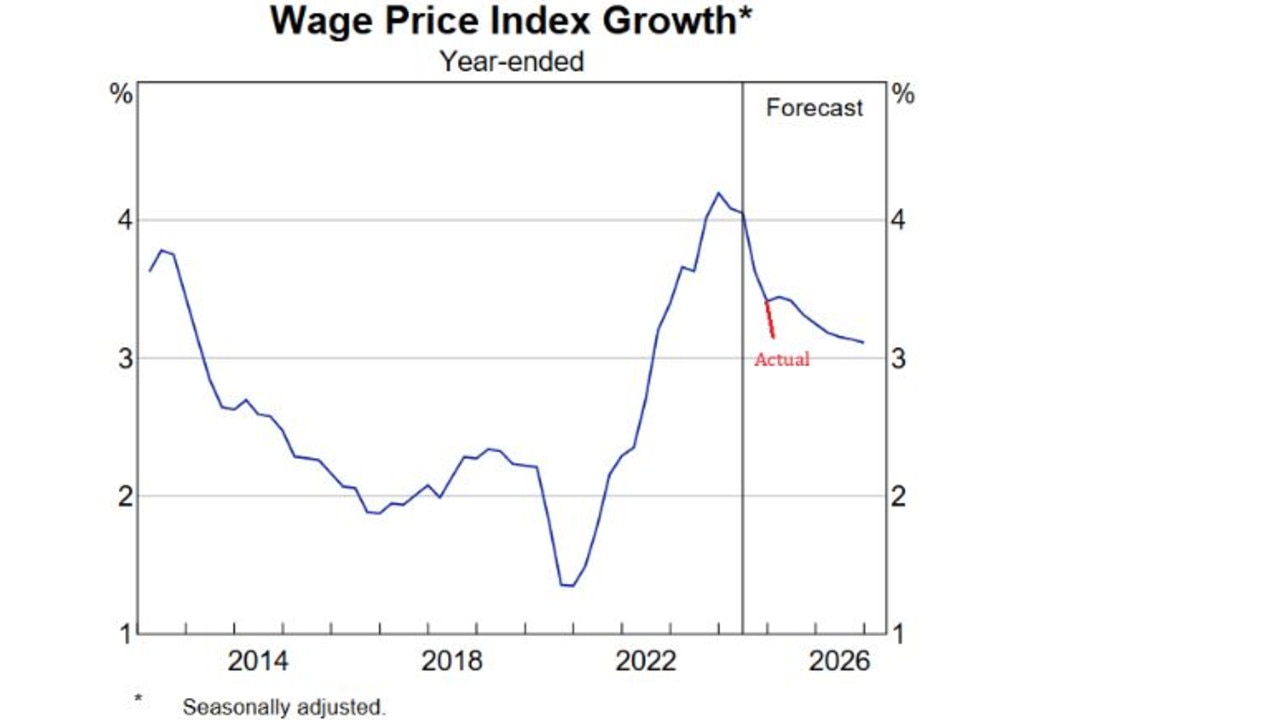

Even wage growth slowed sharply, now growing at just 3.2 per cent six months annualised, a rate entirely consistent with contained inflation of about 2.5 per cent.

Yet, while the data has all turned dovish, markets and commentary have all turned hawkish.

What gives?

The Trump bump

The disjunction between cooling inflation and heating hawks is down to two main developments.

The first is the election of Donald Trump. This is raising inflation expectations for the US, expressed most clearly via rising sovereign interest rates.

However, this is a complete misreading of the impacts of Trump tariffs on Australia.

MORE: Why the RBA must cut interest rates

Here, the Trump agenda will be disinflationary as commodity prices fall and major exporters like China and Europe dump their displaced US goods elsewhere.

A bigger issue

The bigger issue that is upsetting interest rate hawks is Australia’s persistently strong jobs market.

The RBA fears that this will inject a new round of wage inflation into the economy.

This flies in the face of the data, which shows wage growth is 15 months ahead of falling RBA forecasts.

MORE NEWS: Big bank sued for ‘failing’ struggling Aussies

Why is the RBA misreading wages?

Owing to the political correctness of the day, the RBA refuses to assess the impacts of immigration on the economy.

This is pretty crazy, given it is such an enthusiastic supporter of population growth. Not to mention that ignoring such a huge macroeconomic input is barmy.

Yet because the RBA doesn’t do it, neither does anybody else in the interest rate forecasting community.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the vast bulk of Aussie economic analysis is flying blind.

What is the impact of immigration?

Wherever mass immigration has been undertaken in recent years – Australia, Canada, New Zealand etc – the results have been the same.

Productivity crashes as capital shallows. Wages weaken owing to the supply shock. Inflation falls.

MORE: Surprise rates call creates trap for home buyers

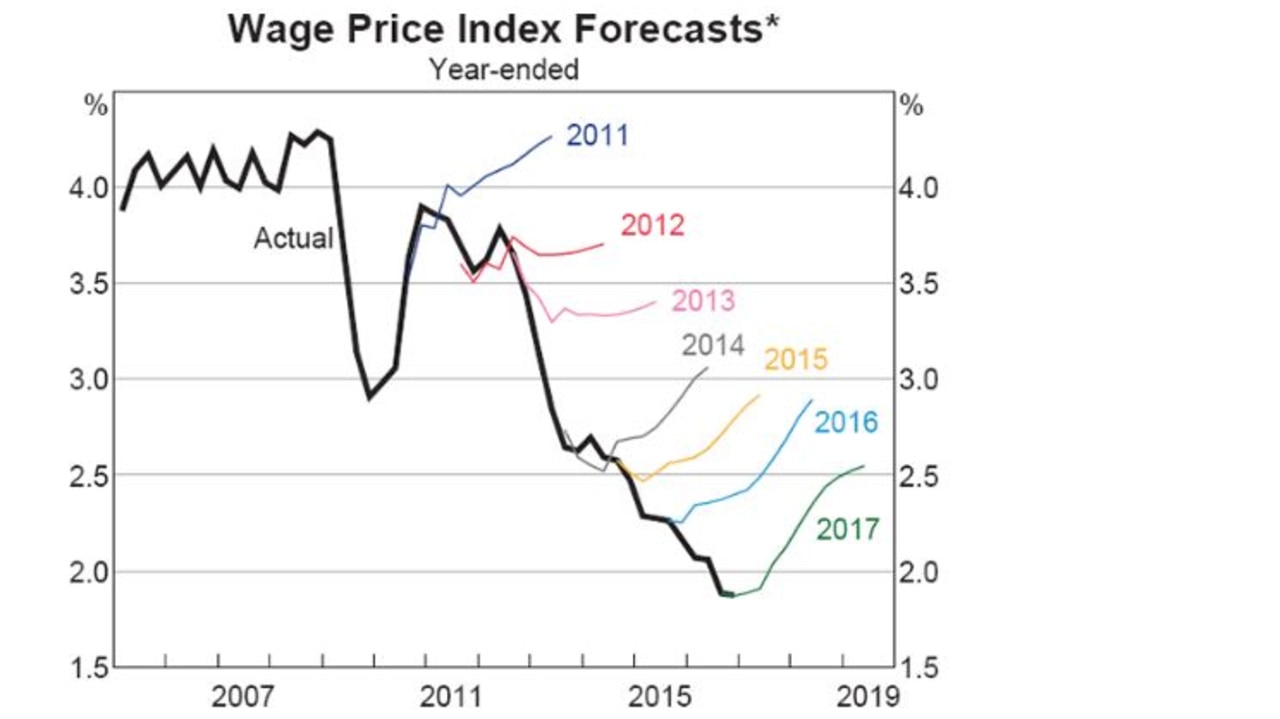

Traditional economic models, like those that the RBA uses, foresee a different outcome.

In those models, falling productivity makes for sticky wages, which holds inflation up.

Instead, the immigration-led economy delivers a permanent supply shock to workers and they lose pricing power.

Falling productivity doesn’t translate to higher prices because company profits rise with population growth.

If the RBA had taken a moment to look out its window during the last cycle, it would have seen this playing out in real time.

Instead, it relied on its models and kept expecting rebounding wages to drive an inflation lift.

In the end, it got so bad that former Governor Philip Lowe was sacked.

But the models persist, and seemingly having learned nothing, the RBA is doing it again.

Is it different this time?

There are a few differences to the last cycle worth mentioning that might make a difference.

The sheer scale of immigration this time is a factor.

Anthony Albanese came to power promising to cut immigration for the precise reason that it would support wages.

But he lied and instead doubled the rate of immigration.

This delivered an inflationary rental shock. However, rents are only 6 per cent of the Consumer Price Index, whereas weaker wages affect most prices, including rents.

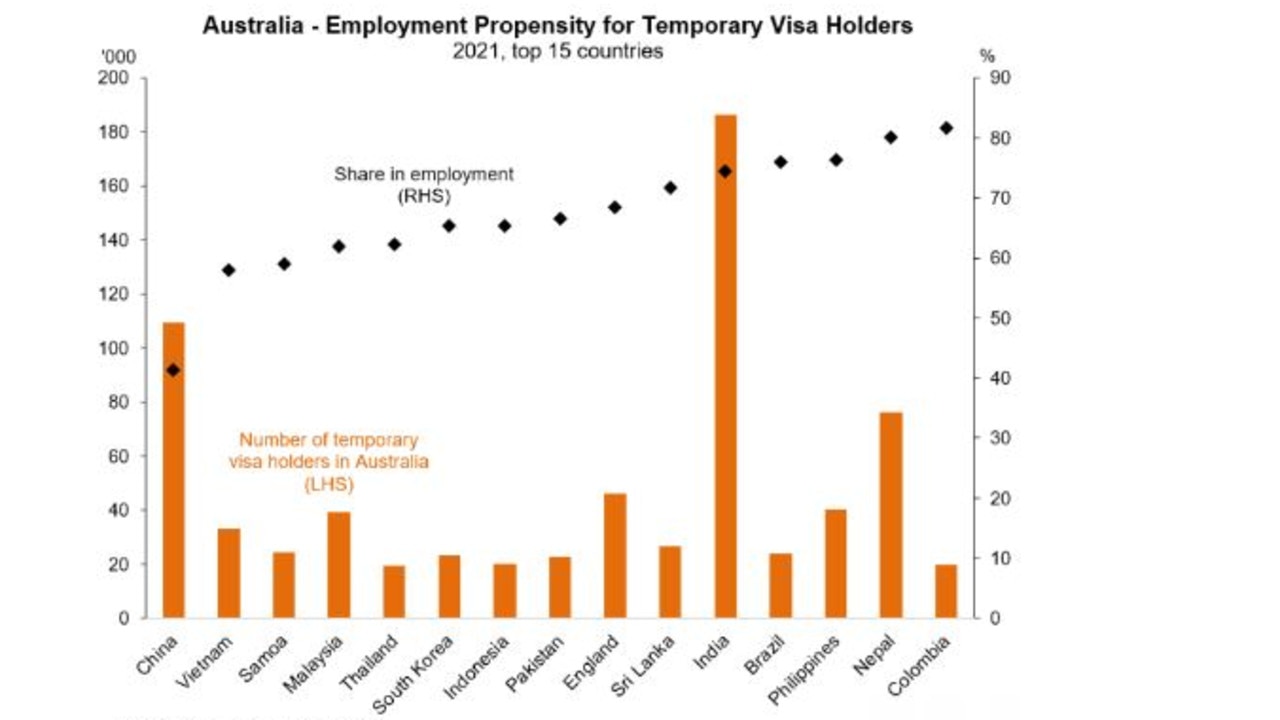

Another factor is that Albo flew to India and tore down the boundaries between their labour market and ours, changing the composition of immigration.

Pre-Covid, wealthy Chinese immigrants who were less likely to work led immigration.

Post-Covid, less well-off Indian immigrants are in charge and are very likely to work.

MORE: Worst areas hit by Albo-economics

International students are also granted 24 hours a week to work, versus 20 hours pre-pandemic.

It doesn’t take Albert Einstein to figure out how these changes are pushing down wage growth.

Inflation will follow and, eventually, even the blinded RBA will wake up to the return of lowflation.

David Llewellyn-Smith is Chief Strategist at the MB Fund and MB Super. David is the founding publisher and editor of MacroBusiness and was the founding publisher and global economy editor of The Diplomat, the Asia Pacific’s leading geopolitics and economics portal. He is the co-author of The Great Crash of 2008 with Ross Garnaut and was the editor of the second Garnaut Climate Change Review