Interest rates are nearing their peak, but the suffering has only just begun

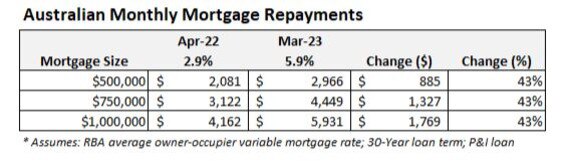

Economists predict the impact on mortgage holders in the coming months will be brutal, with average variable mortgage repayments set to soar by 43 per cent.

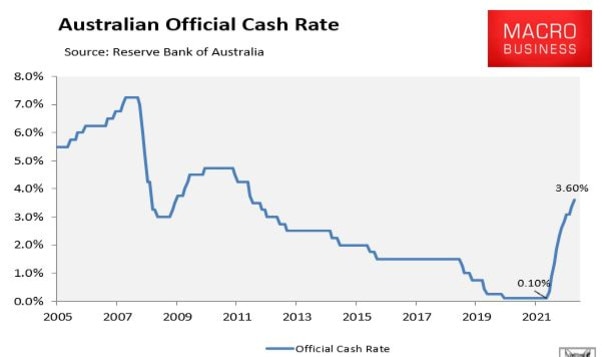

As expected, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) on Tuesday lifted the official cash rate (OCR) another 0.25 per cent to 3.6 per cent.

It was the tenth consecutive rate hike and has taken the OCR to its highest level since 2012:

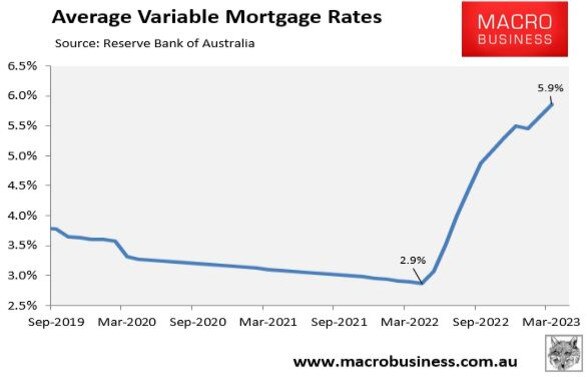

The increase in the OCR has more than doubled average owner-occupier variable mortgage rates from 2.9 per cent in April 2022 to 5.9 per cent after this latest increase:

The impact on mortgage holders will be brutal, with average variable mortgage repayments set to soar by 43 per cent above their pre-tightening level following this OCR increase, which will add around $900 in monthly mortgage repayments on a typical $500,000 mortgage:

The good news is that the RBA minutes accompanying Tuesday’s rate decision took a more dovish tone, suggesting we are approaching the peak in the interest rate cycle.

The key talking point from Tuesday’s monetary policy statement is that the reference to “increases” in interest rates over coming ”months” was dropped.

In the February Statement, the RBA said that “the Board expects that further increases in interest rates will be needed over the months ahead to ensure that inflation returns to target”.

In Tuesday’s statement, that sentences changed to “the Board expects that further tightening of monetary policy will be needed to ensure that inflation returns to target”.

Thus, the plurals are gone, suggesting the RBA is no longer convinced that it needs to hike the OCR multiple times from here.

Indeed, the RBA has even left the door open to freezing the OCR at its current level, should the data come in softer than expected.

The RBA statement explicitly noted that “in assessing when and how much further interest rates need to increase, the Board will be paying close attention to developments in the global economy, trends in household spending and the outlook for inflation and the labour market”.

Based on the “when” in this statement, the RBA has not yet made up its mind on whether it will lift rates again next month, if at all. It will depend on the incoming data.

There were other indications from the RBA that interest rates are nearing their peak.

The RBA appears less concerned around inflation, noting that “the monthly CPI indicator suggests that inflation has peaked in Australia” and ”the central forecast is for inflation to decline this year and next, to be around 3 per cent in mid-2025”.

The RBA also seems less concerned about a wage-price breakout noting that “at the aggregate level, wages growth is still consistent with the inflation target and recent data suggest a lower risk of a cycle in which prices and wages chase one another“.

Finally, the RBA “recognises that monetary policy operates with a lag and that the full effect of the cumulative increase in interest rates is yet to be felt in mortgage payments”.

“Household balance sheets are also being affected by the decline in housing prices”, the statement notes.

Even if the RBA pauses, monetary conditions will tighten:

Regardless of whether the RBA pauses from here, monetary conditions will tighten significantly in the near future.

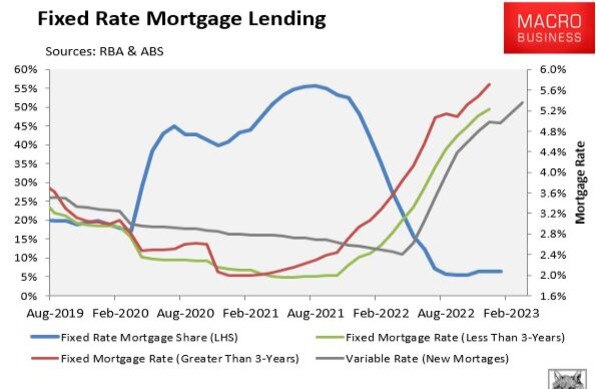

According to RBA’s own estimates, around one third of all home loan borrowers are on fixed mortgages, many of which were originated over the pandemic at rates of around 2 per cent:

Nearly 900,000 borrowers, or 23 per cent of Australia‘s total mortgage book by value, will this year switch from these cheap pandemic fixed rates to variable mortgages with rates that are more than double current levels.

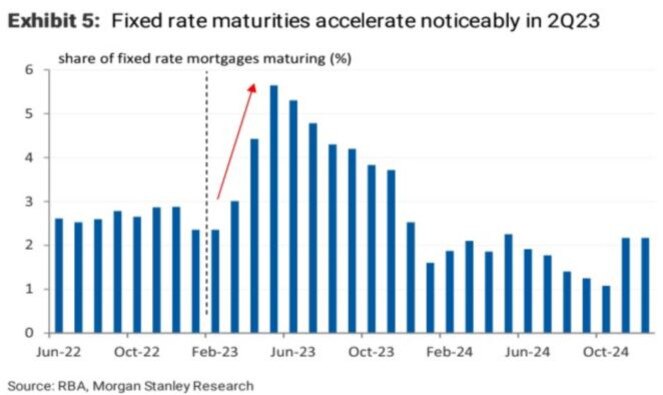

The next chart from Morgan Stanley highlights the extent of this fixed rate “mortgage cliff”, with the volume of fixed rate mortgages expiring rising precipitously from April, peaking in May, and then remaining at high levels through the remainder of this year:

Mortgage rates have already risen beyond 3 percentage points for many borrowers, which is the minimum serviceability buffer required by APRA in assessing whether someone can repay their debt.

Therefore, many thousands of borrowers risk being pulled underwater as their fixed rate terms expire over coming months.

In turn, Australia’s housing market will likely see a significant increase in forced sales, which will pull house prices lower.

Australia risks being thrown into recession:

Last week’s national accounts for the December quarter revealed a sharply slowing economy, and this was before February’s and March’s cumulative 0.5 per cent increase in the OCR.

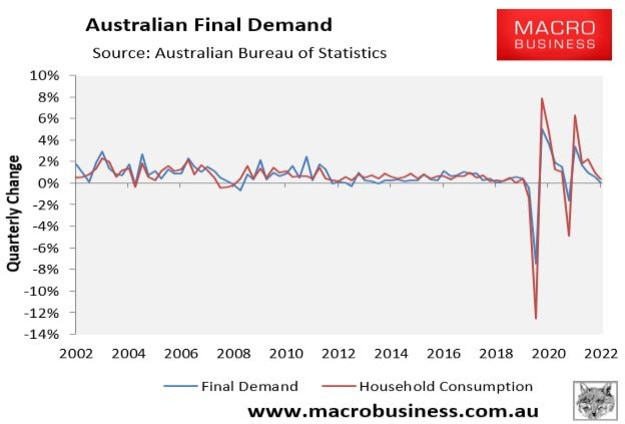

Australia’s final demand, which measures domestic economic activity by stripping away the impact of net exports, was dead flat in the December quarter and actually fell by 0.5 per cent in per capita terms (i.e. after adjusting for population growth).

This slump in growth was driven by soft household consumption, which grew by only 0.3 per cent in the December quarter and fell by 0.2 per cent in per capita terms.

Household consumption is the main driver of the Australian economy and where it goes the economy typically follows:

It is easy to see why household consumption is stalling, given the average compensation of Australian employees has fallen sharply in real terms, slumping to 2012 levels on the back of soft wage growth and high inflation:

Basically, households are pulling back expenditure in the face of falling real wages and increasing interest repayments following the RBA‘s rate hikes.

The situation will only deteriorate from here given the RBA has lifted the OCR another 0.5 per cent since December (with another increase likely), as well as the imminent fixed rate mortgage cliff.

The Australian economy is already teetering on the brink. And if the RBA continues to tighten, it risks plunging the economy into a consumer-led recession.

Leith van Onselen is co-founder of MacroBusiness.com.au and Chief Economist at the MB Fund and MB Super. Leith has previously worked at the Australian Treasury, Victorian Treasury and Goldman Sachs.