Price of common grocery item soars amid inflation increase

Aussies already know today’s inflation number is bad news for the cost of living crisis, but there are some areas being hit harder than others.

Today’s latest inflation number has confirmed what everyone already knows – pretty much everything is becoming more expensive.

The 1.8 per cent figure for the June quarter released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) on Wednesday morning brings the annual inflation rate to 6.1 per cent, the highest reading since 1990.

Higher petrol, groceries, rent and home building costs are all contributing to higher inflation.

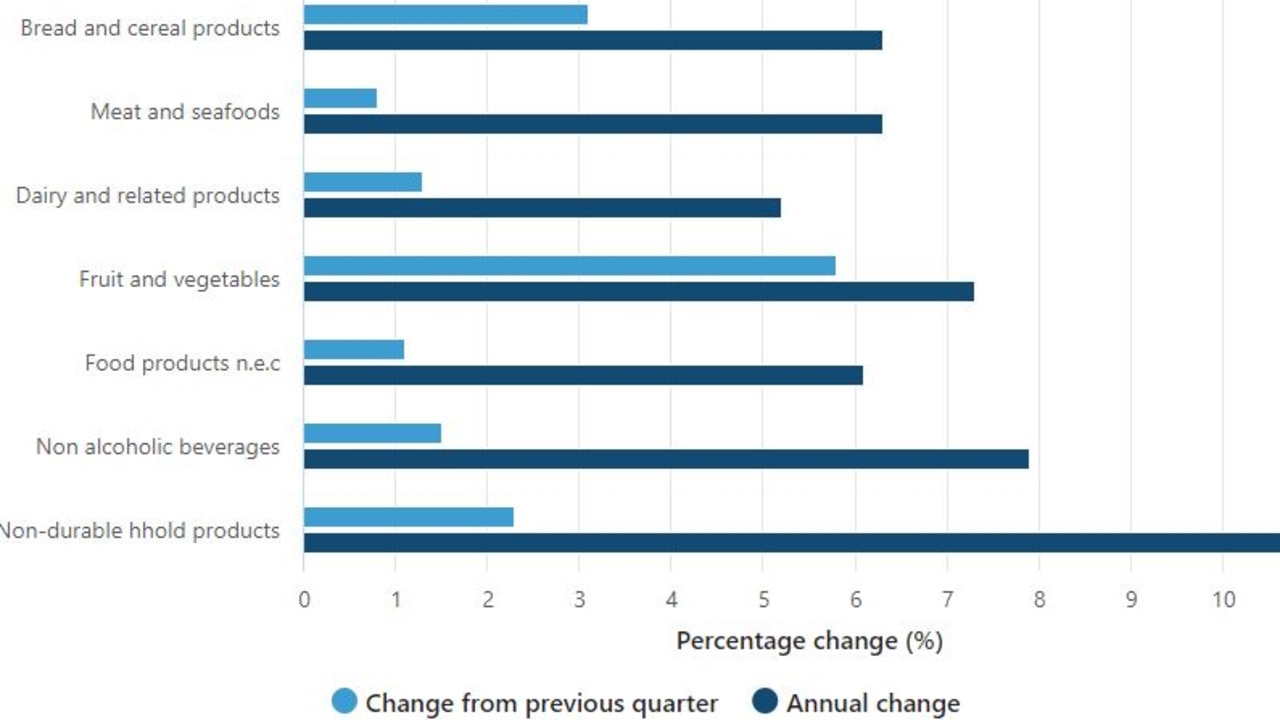

Figures from the ABS show price rises have been seen across almost all grocery items in the June quarter, with fruit and vegetables among the hardest hit.

The cost of fruit and vegetables rose a whopping 7.3 per cent from last year and 5.8 per cent from the previous quarter.

Stream more finance news live & on demand with Flash. 25+ news channels in 1 place. New to Flash? Try 1 month free. Offer ends 31 October, 2022 >

ABC’s Business reporter David Chau described it as “one heck of a price increase for vegetables”.

The price of meat, seafood, bread and cereal products rose 6.3 per cent, while the cost of non-alcoholic beverages rose 7.9 per cent.

The ABS said these changes reflect “a range of price pressures including supply chain disruptions and increased transport and input costs.”

What is inflation?

Inflation is the rate at which prices for goods and services increase, expressed as a percentage.

In general prices tend to go up over time, but sometimes they decrease – which is called deflation.

Inflation is measured every three months, and on an annual basis.

In effect it means the same dollar buys less as time goes on – if inflation is at 3 per cent per year, for example, something you bought for $100 would cost $103 dollars 12 months later.

Over time the effects of inflation can be extreme. A basket of goods and services valued at $100 in 1970 would cost nearly $1200 in 2020, 50 years later, according to the Reserve Bank’s inflation calculator.

What causes inflation?

There are a few different causes of inflation, but broadly it happens in two ways based on the laws of supply and demand – an increase in the amount of money in circulation, or an actual rise in the cost of producing items.

Inflation caused by an increase in the money supply, which economists refer to as demand-pull inflation, is often expressed as “too many dollars chasing too few goods”.

That is generally offset by economic growth. Ideally, the growth in a country’s money supply should roughly keep pace with the growth of its economy – which is the primary mission of central banks like the RBA.

Inflation driven by external factors, called cost-push inflation, is when demand for something remains the same but higher costs of production, such as from rising prices for raw materials, causes an overall reduction in supply.

What is the Consumer Price Index?

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is one measure of inflation.

The ABS keeps track of quarterly changes in the price of a basket of goods and services, to give an overall sense of how much more or less we’re paying for things in everyday life.

The ‘basket’ includes a wide range of items, arranged into eleven groups – food and non-alcoholic beverages; alcohol and tobacco; clothing and footwear; housing; furnishings, household equipment and services; health; transport; communication; recreation and culture; education; insurance and financial services.

Some things like mortgages and land prices are not included in the CPI, as it’s intended to be a measure of everyday expenditure.

How is CPI measured?

The ABS collects prices for various items each month including alcohol, men’s and women’s clothing, project homes, motor vehicles, petrol and holiday travel and accommodation.

More volatile items are measured more frequently while others where prices are changed at infrequent intervals, such as education fees, are collected accordingly.

Prices are collected through a variety of sources including visiting businesses, online collection, telephone surveys and administrative data.

It’s then grouped together into 87 expenditure classes and “weighted” based on the relative importance of each.

Why is inflation so high?

Basically, there has been a double whammy of cost-push and demand-pull inflation over the past two years.

As they shut down their economies during the pandemic, governments around the world handed out billions of dollars in stimulus to citizens while central banks slashed interest rates to near-zero levels.

That drastically increased the amount of money sloshing around, while also increasing consumer demand – lots of people sitting at home buying stuff on Amazon.

But at the same time, the real-world consequences of lockdowns – closed borders, production shutdowns, shipping delays – restricted the supply of goods, causing prices to rise.

Australians were already seeing higher prices for many imported goods due to supply chain disruptions, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the start of the year caused further turmoil as it sent global prices for energy and other commodities skyrocketing.

Higher fuel costs are particularly devastating, as they drive up prices for nearly everything else.

In Australia, the floods have also been a factor, disrupting growing season and impacting the supply of fresh fruit and vegetables.

The RBA has warned inflation is likely to hit 7 per cent before the end of the year.

When was inflation this bad before?

Across most of the world, inflation is at the highest level in decades. Inflation in Australia hasn’t been this high since 1990, 32 years ago.

In the US and UK, inflation is at 40-year highs of 9.1 per cent and 8.2 per cent. New Zealand is at a 32-year high of 7.2 per cent.

This is far from the worst it’s been, however. In March 1975, at the height of the global oil price shocks that saw fuel prices skyrocket, the annual inflation rate in Australia hit 17.7 per cent.

But the highest inflation ever seen in Australia was actually 23.9 per cent in December 1951, during the “Korean War Boom”.

A large factor was the surging global demand for wool, one of Australia’s key exports, with tripling prices leading to a massive increase in GDP growth, pushing up domestic demand.

At the same time, the Australian government was removing controls over prices, wages and rationing – further increasing domestic demand – and embarking on expansionary post-war fiscal and monetary policies including cheap home loans.

And much like today, global supply chains were still struggling to recover after World War II.

What is the inflation target?

The RBA is tasked by the government with maintaining an inflation rate of between 2-3 per cent on average over time.

“This is a rate of inflation sufficiently low that it does not materially distort economic decisions in the community,” the RBA says.

“Seeking to achieve this rate, on average, provides discipline for monetary policy decision-making, and serves as an anchor for private-sector inflation expectations.”

The central bank achieves this by controlling the money supply through tweaking interest rates on the first Tuesday of each month, except January, in order to stimulate or slow down economic activity.

Officially the RBA sets what’s called the cash rate target, which dictates the overnight interest rate banks charge to lend money to one another. That in turn flows through to interest rates banks charge customers for mortgages, car loans, and also to how much interest banks pay on savings accounts.

Can the RBA solve the problem?

The RBA’s sole lever of moving interest rates up or down can only affect the demand side of the equation.

When inflation is largely being driven by external forces, particularly overseas ones, it’s more difficult. The key to solving cost-push inflation is by reducing production costs.

RBA governor Philip Lowe said in a speech last week that bringing inflation back to the target level would require a combination of higher interest rates and supply-side fixes.

“Looking forward, the path back to 2-3 per cent inflation requires an increase in supply and some moderation of demand,” Dr Lowe said.

“In terms of the supply side, there is a reasonable basis to expect that Covid-related disruptions to global supply chains will ease further over the months ahead. Delivery times are improving and some supply bottlenecks are easing as firms adjust to the new operating environment.

“The effects of this and some rebalancing in consumer demand are now evident in some global markets, with declines in the global prices of products as diverse as computer chips and timber.”

Dr Lowe added that prices of many commodities including oil, wheat and base metals had declined over recent weeks.

“If the lower prices are sustained, this will ease some of the current global inflation pressures,” he said.

“Even so, it remains possible that there will be further interruptions to global supply, once again pushing up prices – the European gas market is a particular area of concern here.”

Domestically, the economy has bounced back strongly, with unemployment at a 50-year low of 3.5 per cent, and job vacancies are at historically high levels across most industries.

“This all suggests that the growth in demand in the Australian economy is pushing up against the capacity of the economy to meet that demand,” Dr Lowe said.

How bad will it get?

To combat soaring inflation, the RBA has delivered three back-to-back rate hikes in May, June and July of 25, 50 and 50 basis points, bringing the cash rate to 1.35 per cent.

Economists have warned the cash rate could pass 3 per cent before Christmas.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers, who is set to deliver an economic statement to parliament on Thursday, has warned of more pain to come.

The International Monetary Fund says the world is “teetering on the edge of a global recession” in its July 2022 Economic Outlook, with Australia’s economy forecast to grow at 2.9 per cent this year and 2.7 per cent in 2023.

“This confirms the challenges facing the global economy are substantial, they are growing, they will be with us for some time, and they are impacting us here at home,” Dr Chalmers told The Australian Financial Review.

“After nine years of wasted opportunities and wrong priorities, we have inherited an economy that is less resilient in responding to these shocks, but we are determined to turn this around and build a better future.”

The IMF report said controlling inflation should be a major priority for governments.

“Tighter monetary policy will inevitably have real economic costs, but delay will only exacerbate them,” it said.

“Policies to address specific impacts on energy and food prices should focus on those most affected without distorting prices.”