What end of ATO’s JobKeeper means for Australia’s economy

The clock is ticking until Australians will have to face the reality of what the pandemic has done to our economy. Here’s how it could play out.

After a year of being heavily supported by hundreds of billions of dollars of government stimulus programs, on March 31 the Aussie economy will finally begin to stand on its own two feet.

With JobKeeper and the JobSeeker supplement set to come to an end, households and businesses will soon once again find themselves operating without the most generous government safety net in the history of the nation.

But as more than $300 billion in stimulus over the past 11 months is tapered down to just a fraction of that, one has to ask, what is going to drive the economy going forward?

In short – the savings of households and businesses made during the pandemic.

According to Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, households and businesses have squirrelled away around $200 billion in savings since the pandemic began.

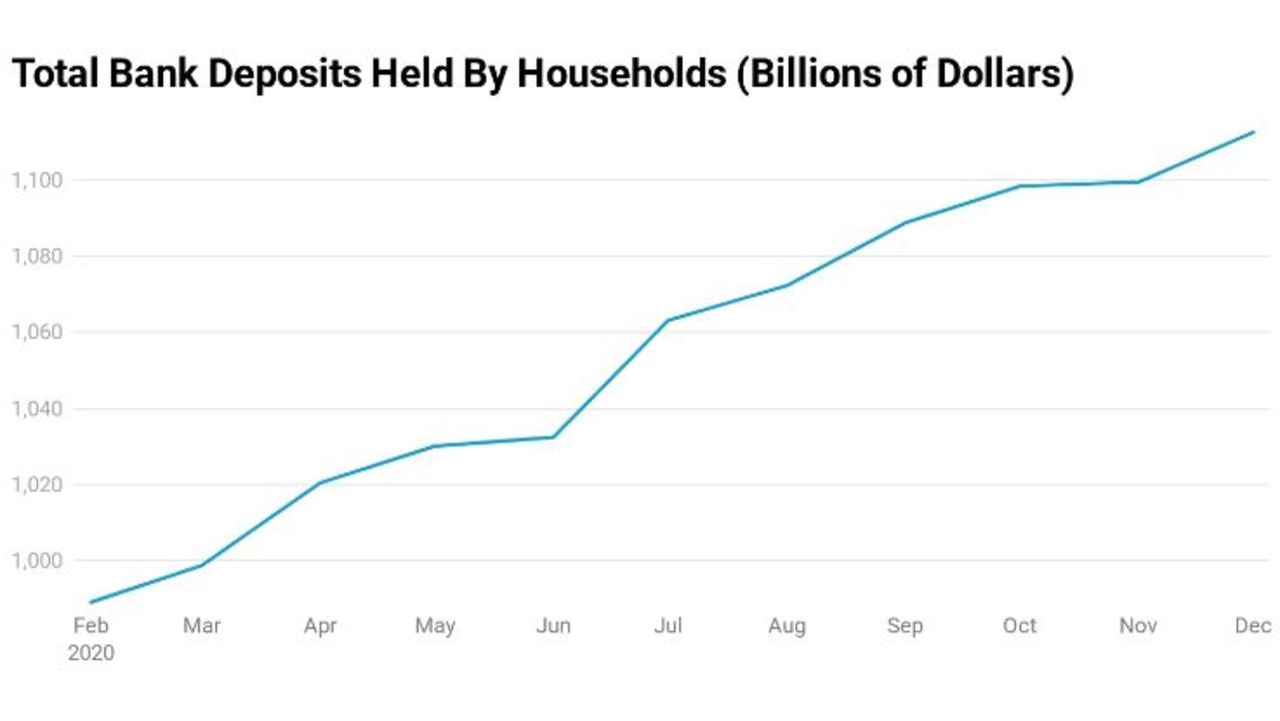

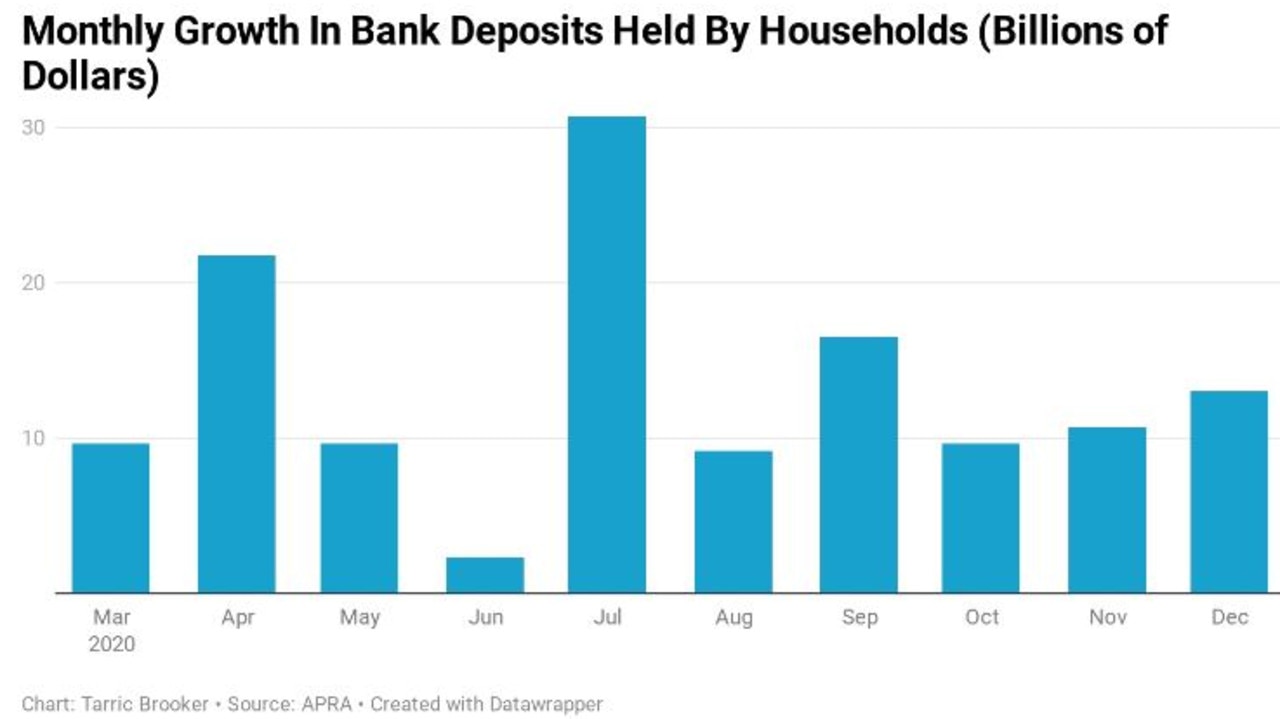

With so much uncertainty stemming from the pandemic and also the opportunity to withdraw superannuation for a rainy day, households put aside more than $113 billion in the nine months to December.

RELATED: Qantas boss’s dire warning

Now as the bulk of the Morrison Government’s support measures begin to taper off, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg is expecting quite a lot from households and businesses.

“This money will help underpin our economic recovery and avoid a fiscal cliff as some of the support measures start to taper off,” Mr Frydenberg said.

The Treasurer added that it was not his place to tell anybody how or where to spend their money, but he was confident that much of it would go towards boosting Australia’s economy.

This leads us to the $2 trillion question (roughly the size of the Aussie economy): Will households and businesses actually spend sufficiently?

From the perspective of Aussie businesses, it’s not looking flash.

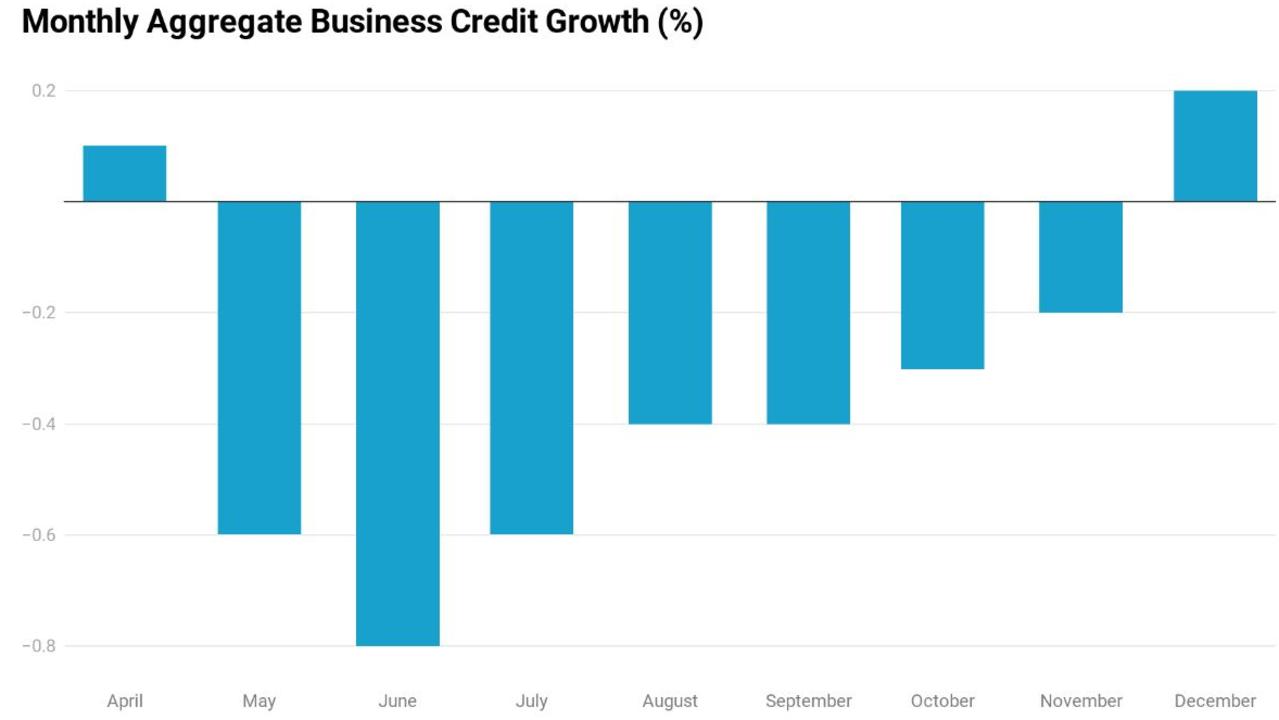

Since April last year, total outstanding business credit has contracted by 3.1 per cent. Business owners have been paying down their existing debts and generally appear to be quite reticent about taking on another loan in this environment.

While some green shoots have emerged in the latest figures showing 0.2 per cent growth for the month of December, it’s unlikely that this anaemic level of business investment will support the economy much going forward.

RELATED: Super withdrawals could see housing market boom

Even before the pandemic things weren’t looking good for business investment. In December 2019, shortly before the pandemic began, annual growth in business investment was just one tenth of what it was compared with its peak prior to the global financial crisis.

With the uncertainty surrounding the pandemic, the reopening of international borders and the state of the economy unlikely to be resolved any time soon, Aussie businesses may continue to be conservative with their cash.

That’s one half of the structure expected to support the economy already looking shaky, unless we see a major turnaround.

So that likely leaves households to once again act as Australia’s version of Atlas, to hold up an otherwise mostly anaemic economy.

This leads us to two vital questions for the economy going forward.

Will households feel comfortable enough to spend their savings?

And are the households who hold those savings likely to spend them in ways that benefit the broader economy?

While households are confident about their future according various consumer sentiment surveys, when it comes to spending their savings and/or rainy day funds, they appear to be much more cautious.

According to a news.com.au poll, just 19 per cent of respondents said they would spend their savings from March, with 45 per cent stating they wouldn’t due to uncertain future and a further 36 per cent having no savings to spend.

These numbers are supported by household survey data from research firm Digital Finance Analytics (DFA). According to DFA’s data, roughly one third of Aussie households have little to no savings.

In lockdown-hit Victoria, things are even more dire. Almost 40 per cent of all households have little to no savings to fall back on as the various government support programs such as JobKeeper and the JobSeeker supplement come to an end.

But among wealthier demographics the story is quite different. In “exclusive professionals” as defined by the DFA, the average household has over $34,000 in savings.

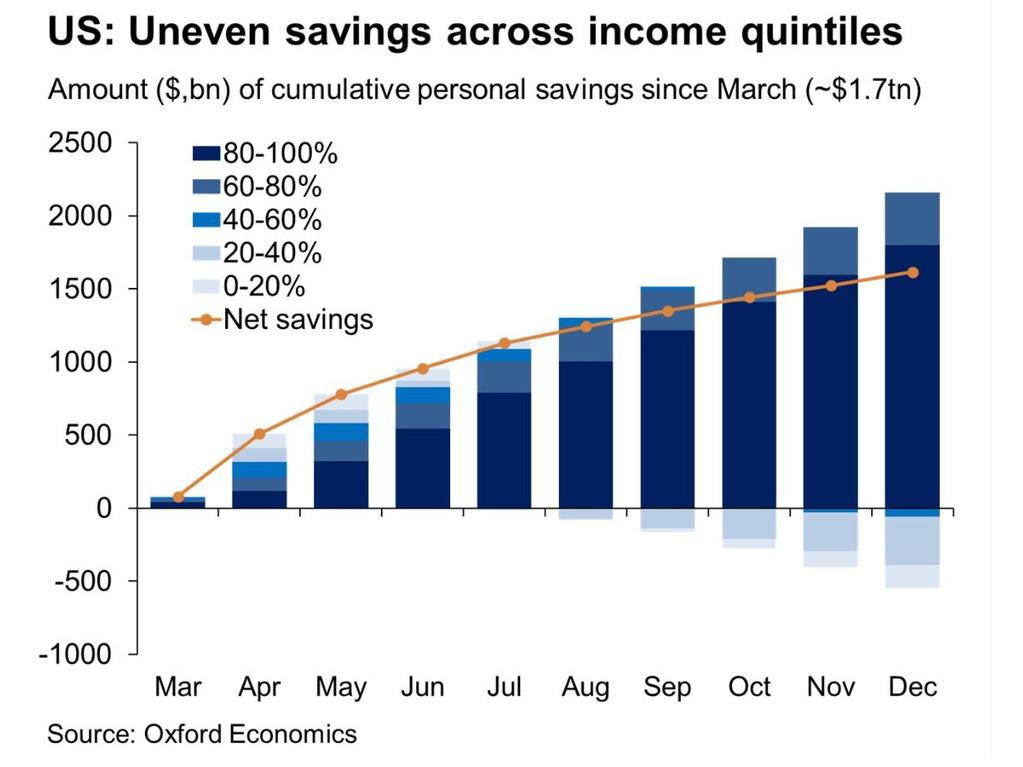

Despite having a very different experience in coping with the virus, the trend of lower income households having little savings to fall back on and wealthier households having quite the war chest is similar in the United States.

RELATED: ‘Pay it back’: Fashion label under fire

In the US, the bottom 60 per cent of households by income have burned through around $500 billion of their pre-pandemic savings. At the same time, the top 20 per cent have built a veritable king’s ransom of around $1.75 trillion in savings made since the pandemic began.

This leaves the economy in quite a precarious position. Generally the wealthy tend to invest their savings in financially productive investments, while lower income households more readily use them for consumption.

As it stands, the balance of savings is likely to offer some support to the economy as the various government support measures are tapered and removed.

However, even if the more well-off spend a large portion of their savings, the impact on the broader economy may be more limited than the Treasurer has predicted.

Rocketing sales at businesses frequented by the well-off may not provide that much of a boost, when the bottom third of households have little to no savings with which to spend on supporting businesses in their local area.

As the clock ticks down to the time the Aussie economy will be forced to stand on its own two feet, this data provides a concerning picture of what may lay ahead.

It appears more well-off households may see economic activity continue to hum along at a steady pace. But for less affluent ones, particularly those in Victoria, a challenging time may lay ahead.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator