‘Unprecedented going back to 1959’: Australians’ living standards will take years to recover

Almost everyone was celebrating when the RBA cut rates this week, but there was one ominous detail that shows how far we’ve fallen.

Australia might not return to its pre-Covid level of living standards until about 2030, the federal opposition is arguing, citing the latest data from the Reserve Bank.

The RBA cut the cash rate to 4.1 per cent on Tuesday, the first time the official rate had decreased since November of 2020. Interest rates had been on hold for more than year, after a sequence of 13 hikes between May of 2022 and November of 2023.

“This doesn’t solve all the problems, of course. It’s just one decrease. But it does show that things are heading in the right direction. It is positive,” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese told WSFM radio on Wednesday, stressing that the rate cut was “welcome news”.

“It’s been hard. Inflation had a six in front of it when we came to office. Now it’s got a two in front of it, and is going down.”

OK, sure. But as the opposition has pointed out, Australians are still struggling – and will likely continue to struggle for some time.

“Living standards have collapsed in an unprecedented way in Australia, more than at any other time in our history, and further downgrades in living standards came out in the Reserve Bank’s forecast, despite the interest rate cut,” Shadow Treasurer Angus Taylor said after the RBA board’s decision.

“It’s a long journey back to where Australians were.”

He described recent years – the years coinciding with Labor’s period in power, of course, and conspicuously timed not to overlap with the Coalition’s term in government – as “an economic catastrophe for Australian households”.

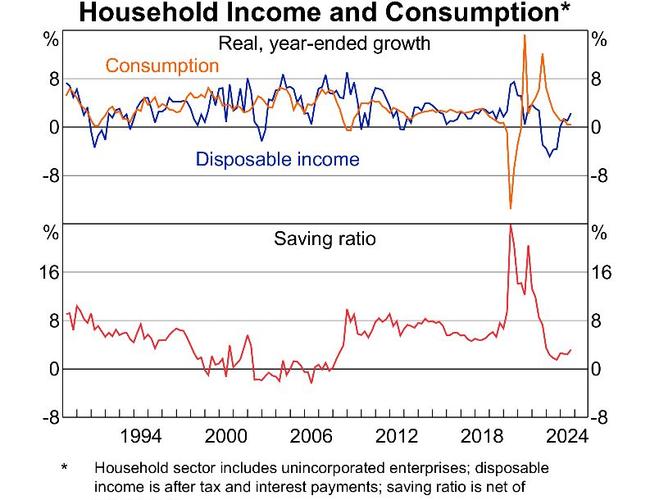

The metric we are chiefly talking about, here, is households’ disposable income. It took a whopping hit around the back end of the Covid pandemic, between 2021 and 2023, and has barely recovered since.

The talking point, from Mr Taylor, is not new. He has been saying similar things for some time. But it was reinforced by Tuesday’s figures.

He is not without a valid argument. But as you would expect from a politician, he has oversimplified the situation.

“Real household disposable income, per head – which is the best measure we have of individual, material living standards – has fallen by close to 10 per cent from its peak. And that is unprecedented, going back to 1959,” independent economist Saul Eslake told news.com.au.

“And it is worse than in any comparable country.”

Mr Eslake identified three primary causes for this discrepancy between Australia and other, similar nations.

First, Australia did not experience the same “surge in nominal wages”, meaning “real wages have fallen in Australia more than in other countries”.

Second, Australia’s taxes have “taken a record bite out of pre-tax incomes”. This is largely due to our taxes not being indexed, which creates bracket creep.

“The proportion of income taken in tax has been higher, in the last three or four years, than at any time at least going back before the introduction of the GST,” said Mr Eslake.

“That was a much more important drag on household income than in countries where the tax scale is indexed.”

Finally, households have “an awful lot of debt”, most of it issued with floating interest rates, whereas in other nations a greater proportion of debt is held with fixed rates.

“So interest rates have taken a much bigger bite out of disposable income,” Mr Eslake said.

Who’s to blame?

Two obvious questions spring to mind. First, how much of this should be blamed on the government? And second, what can Australia do about it?

The answer to the first is: a fair bit. But not all of it, and not just the current government. The crisis has deeper roots.

Significant parts of the problem can be traced back to “long before Albanese came to power”, Mr Eslake argued.

“The industrial relations framework, (for example), which provides the inertia in setting wages for a pretty significant chunk of the workforce. That had been put in place over, what, almost 30 years? Beginning with the Keating government, and continuing through Howard and Gillard and Abbott and his successors,” he said.

“That’s not the fault of this government. (And) it’s not the fault of this government that our tax scales aren’t indexed.”

Of course, the current government hasn’t fixed the tax indexation issue, for instance. But it didn’t create the problem either.

Other factors are not unique to Australia, but are instead an echo of events worldwide, such as the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Think about why we had the inflation that we had in Australia,” said Mr Eslake.

“Essentially, three reasons. One was common around essentially every advanced economy. To some extent – you say this with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight – there was too much stimulus for too long. Which meant that aggregate demand exceeded supply.

“Almost every central bank in the world kept interest rates too low, for too long. And most governments kept fiscal stimulus up for too long. Who was in charge when all that fiscal and monetary stimulus was being applied? It wasn’t Albanese.

“Another cause of the inflation was Covid-related supply chain disruptions. Can’t blame Albanese for that. And the third thing, of course, was the impact on energy prices and some food prices from Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.”

One other major element, always worth mentioning, is the cost of housing, which has worsened over decades because of governments focusing on demand side policies and neglecting the supply side. Or as Mr Eslake put it, “all the stupid subsidies”.

“Whenever it looks like house prices might fall, which you might think, if you were concerned about housing affordability and the cost of living, you’d actually welcome that, ‘Oh my god, house prices are going to fall. We’d better do something that stops it.’ And the usual reaction is to throw cash at people so they can spend more on housing,” he said.

“The other thing that has driven house prices and rents up was the huge increase in migration,” he added.

And that migration has happened under successive governments. So when we’re assigning blame, it’s important not to oversimplify the matter.

“(The public) says, ‘The Titanic has hit the iceberg. It’s the fault of the guy who was on the bridge at the time.’ They don’t say, ‘Who was it who set the course?’” said Mr Eslake.

“That’s the point. Almost all of the inflation we’ve had, and the impact that has had on people’s living standards, is the result of (longer term policies).

“What I’m not saying is that Albanese and (Treasurer Jim) Chalmers have handled this as best they could.”

‘Broadly right’: Grim forecast is, sadly, accurate

Of course, throwing around blame doesn’t actually help us. And the opposition’s claim that living standards will take years, yet, to recover is “broadly” accurate.

“I think Angus Taylor is broadly right,” said Mr Eslake (though he also said Mr Taylor’s effort to tie the problem solely to the Albanese government was “crap”).

“If real household disposable income has fallen by almost 10 per cent over the last three years, which it has, in good times real per capita disposable incomes might be rising by 2 to 3 per cent per year.

“So it makes sense that it’s going to take three or four years to make up that fall. So yes, that’s probably right.

“What can the government do? Well, the government has, to some extent prolonged the period in which inflation was unacceptably high – actually I should say governments, plural – by the amount of spending they’ve undertaken.

“That has added to aggregate demand. But I want to be clear here that I use governments, plural. Because the states have been almost as responsible for the level of public spending as the feds.

“Most of (the states’) spending has been funded by deficit. By debt. Whereas at least the feds can say they’ve run surpluses.”

There’s an awkward trade-off involved, here, that is difficult for anyone in politics, and in the business of winning elections, to reconcile.

“The federal government could have been a bit less inclined to spend money. Having said that, if they hadn’t, we might well have had some quarters of negative growth,” he said.

“The irony is, both of the propositions that have been advanced by Taylor and Chalmers are true. Taylor is right, and others are right, when they say that spending by governments, plural, has added to aggregate demand and made the Reserve Bank’s task of bringing inflation down more difficult. That’s true.

“But Chalmers is also right in saying that if governments had not spent, we might have had a recession. That government spending has helped keep us out of recession. They’re both true.”

Australia, via both the government and the Reserve Bank, “took a different strategy” to our peers overseas, Mr Eslake argued.

“(We were) willing to tolerate inflation being above the target for a bit longer, not raising rates as much. But the other side of the equation is the unemployment rate has hardly gone up at all,” he said.

Mr Eslake said the Prime Minister and Treasurer were “either unwilling or unable to articulate a coherent economic argument”.

“Albanese has been spectacularly incapable of making a persuasive argument about anything. The most successful argument he’s advanced was why we shouldn’t elect Morrison. And it’s not like the people really needed to be persuaded of that anyway,” he said.

What can be done?

The economist argued that measures aimed at increasing Australia’s productivity would be most likely to accelerate the improvement in our living standards, and to do it in a “material and sustainable” way.

“That takes time. There is no quick fix here,” he stressed.

“As an economist though, that is where I’d start. Do things! You have got two reports from the Productivity Commission that have been gathering dust since 2017. You’ve got almost 90 recommendations as to what you could do. Go and do them.

“Tax reform. In particular tax reform that gets rid of fiscal drag, which was one of the sources of why household income has been so weak.”

Again, there are trade-offs. Eliminating fiscal drag – people slipping into higher tax brackets, and thus paying more – would “cost money”. It would “deprive the government of automatic increases in revenue”. And that would compel the government to seek revenue elsewhere.

Of course, it would also rob our politicians of the chance to frequently announce tax cuts.

What else? The system could be reformed to not privilege, so much, income from sources other than wages.

“Forty-seven per cent of the taxable income declared by people in the top tax bracket is from sources other than wages and salaries,” said Mr Eslake.

“It’s capital gains, it’s rent, it’s income from trusts. And all of that is concessionally taxed, relative to wages. Whereas 82 per cent of the income for people who are not in the top tax bracket is wages and salaries.

“Sensible tax reform would be about reducing the concessionality of the way that income, that accrues predominantly to higher income earners, is taxed. And then the quid pro quo would be that you lift the threshold to something like $400,000.

“What you’re basically saying is that you don’t pay the top tax rate until your income is close to $400,000, but once you reach it, you pay the top rate on all that income.”

Will any politicians actually end up proposing these ideas at the election? The answer might be imminent. Do try to contain your excitement.