‘Unemployment could rise significantly’: Expert reveals ‘warning signs’ for Aussie economy

Data has revealed the nation’s economy remains “uncomfortably reliant” one thing – and it could be setting us up for a major crash.

ANALYSIS

In the long history of Australia’s economy, it has earnt a reputation as “The Lucky Country”, dodging economic downturns and recessions even as other developed nations or those in our region grappled with them.

But behind the headlines of success, is the nation’s economy still worthy of that title – or does delving into the details reveal quite a different picture?

When looking at the nation’s labour market, at first glance, it appears that lady luck is once again smiling on our Great Southern Land, with more than 430,000 jobs created in the 12 months to October.

But when you start to get into the details of job creation over the last year, it becomes clear that luck had very little to do with it.

The most detailed and accurate employment statistics the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has at its disposal, the quarterly Labour Account, reveals an economy increasingly reliant on government at all levels to drive job creation.

The ABS defines jobs in public administration and safety, education and training and healthcare and social assistance as “non-market” jobs. While not necessarily directly public sector jobs, the overwhelming majority of jobs in these industries are at least in part government funded.

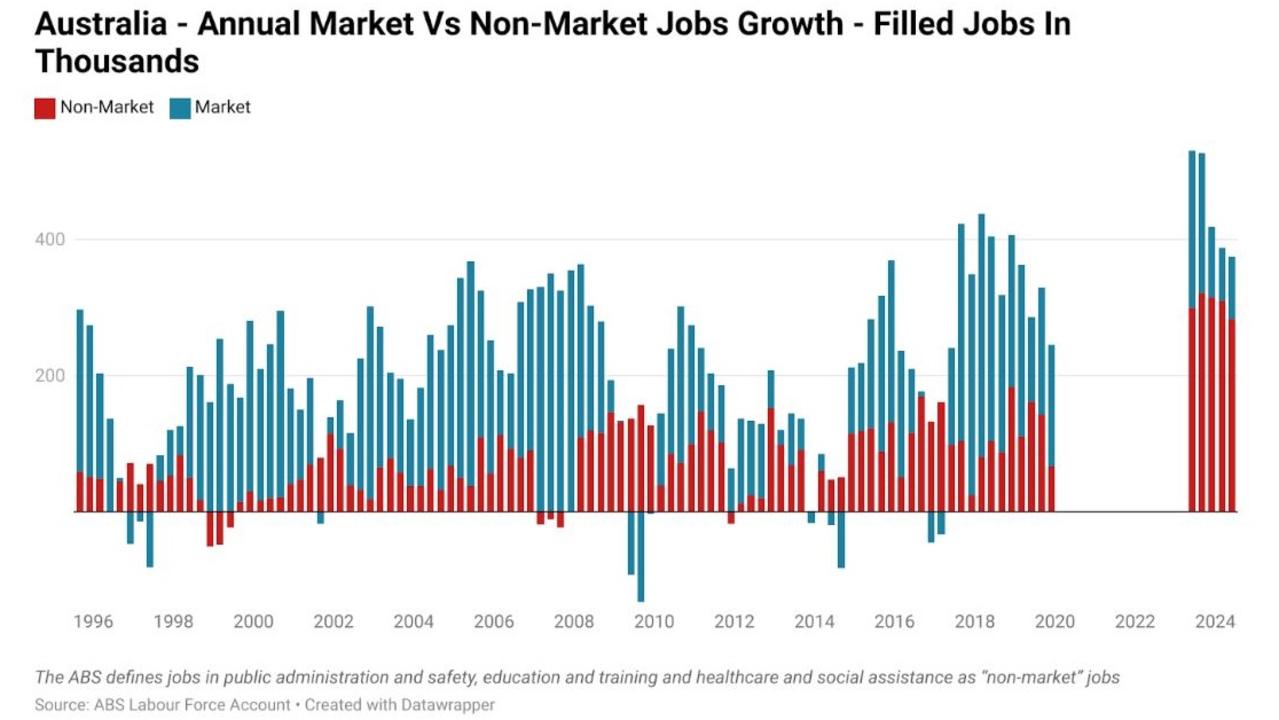

Of the 375,100 jobs created in the 12 months to June, 283,000 were in what the ABS terms non-market industries. Just 92,100 jobs were created in all the remaining industries combined.

In an economy where the labour force expanded by more than 420,000 people in the 12 months to June, this is a concerning development.

Public-private split

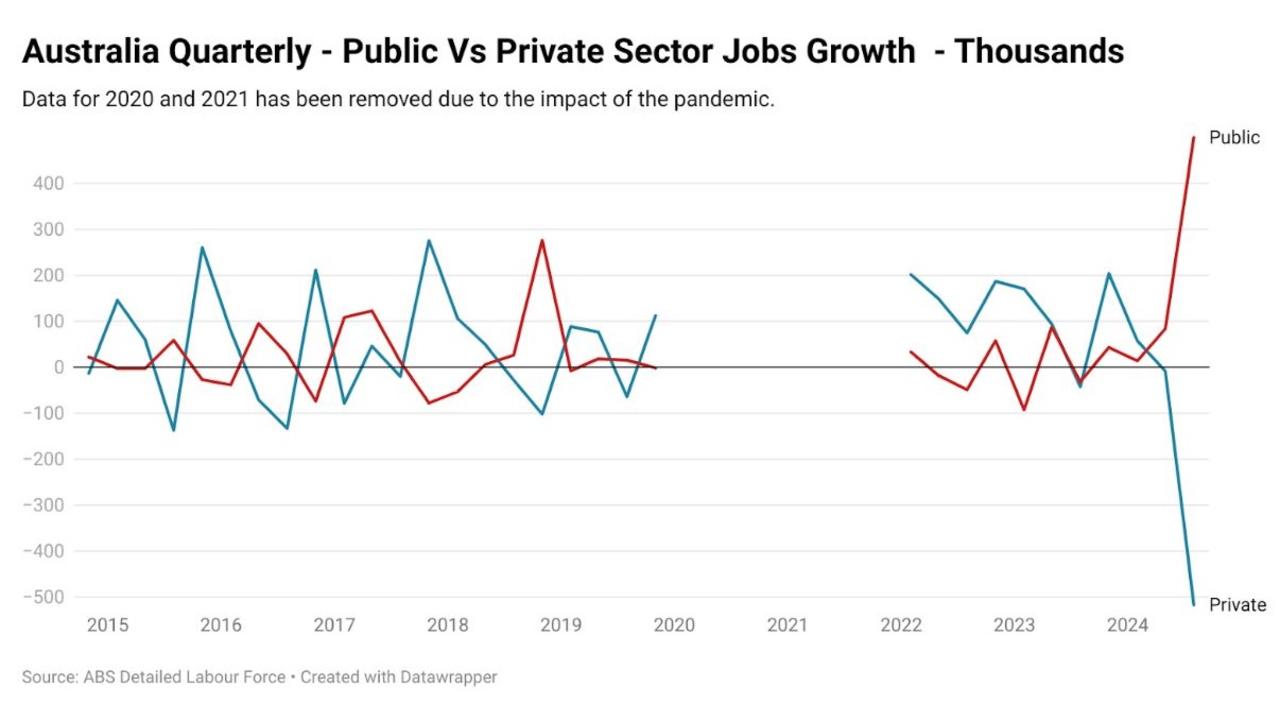

In terms of the actual split between public versus private sector jobs, the figures are even more concerning.

In the 12 months to the end of September, 264,200 private sector jobs have been lost and 639,000 public sector jobs had been gained.

On a quarterly basis, public sector jobs rose by 499,000 and private sector jobs fell by 516,200.

In researching this article, issues with the quality of the split in public versus private sector job creation were raised by several accomplished economists.

The ABS also recently noted this, stating that the figures “should be used with caution”. However, there is an argument to be made that the public versus private split data is playing catch up with the trends seen in the Labour Account and public sector employment payroll data.

The best that can be said for the labour force survey measure of public-sector employment is that it has caught up to the (much) better annual measure based on payroll data. https://t.co/9s71DESWfEpic.twitter.com/SZW5sGjy1L

— Antipodean Macro (@AntipodeanMacro) November 7, 2024

This is not new

While the annual growth in non-market jobs has reached all-time highs in recent years, the shift toward jobs in generally government funded industries taking on a much larger role in overall job creation has been a feature of the economy since the Global Financial Crisis.

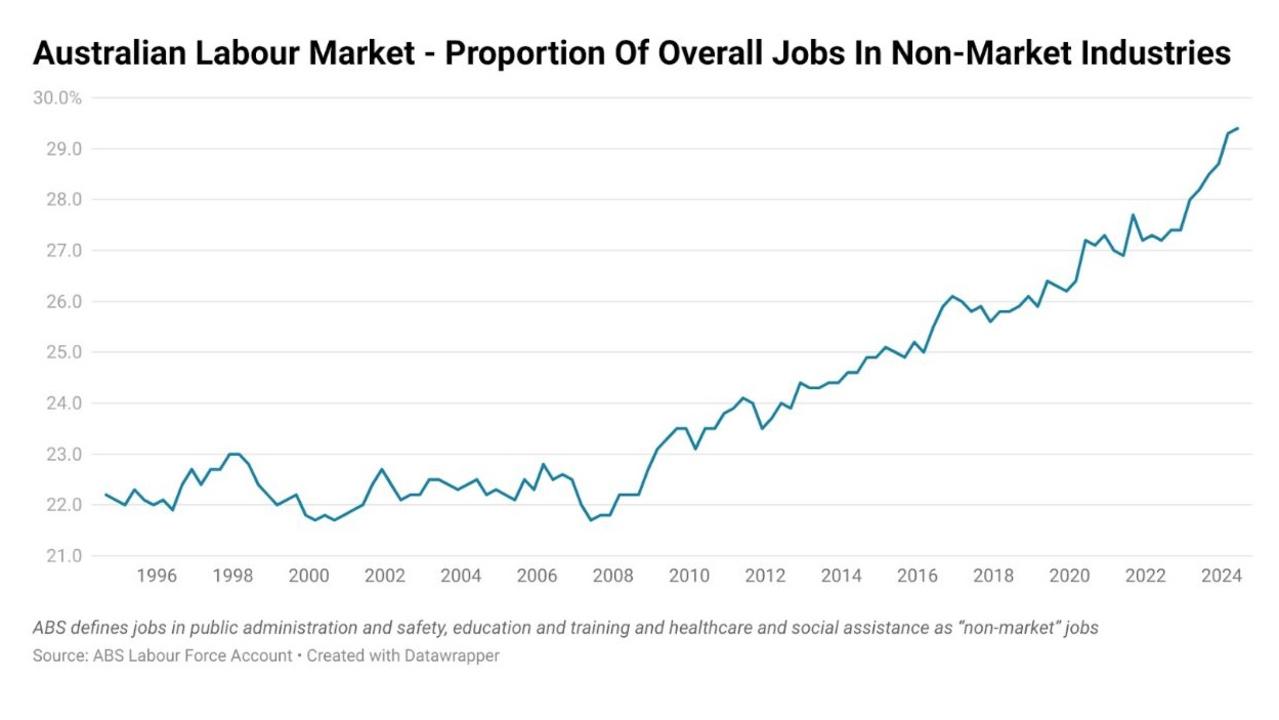

Prior to the GFC, the ratio of non-market jobs to overall employment was relatively stable, moving in a limited range between the start of the data set in 1994 and 2008.

During this era, between 21.7 per cent and 23.0 per cent of overall employment was in non-market based jobs.

In the 16 years since, the proportion of overall employment in non-market based industries has continued to grow and grow, with 29.4 per cent of the overall workforce in those sectors as of the latest data.

In terms of more recent history, the advent of the pandemic saw a strong surge in the proportion of overall employment in non-market sectors, rising from 26.2 per cent in December 2019 to a peak of 27.7 per cent in September 2021, before falling back to 27.2 per cent in the quarter in which the Albanese government came to power.

Since then, the ratio of non-market jobs to the overall workforce has risen to a record high of 29.4 per cent.

Non-market jobs versus everything else

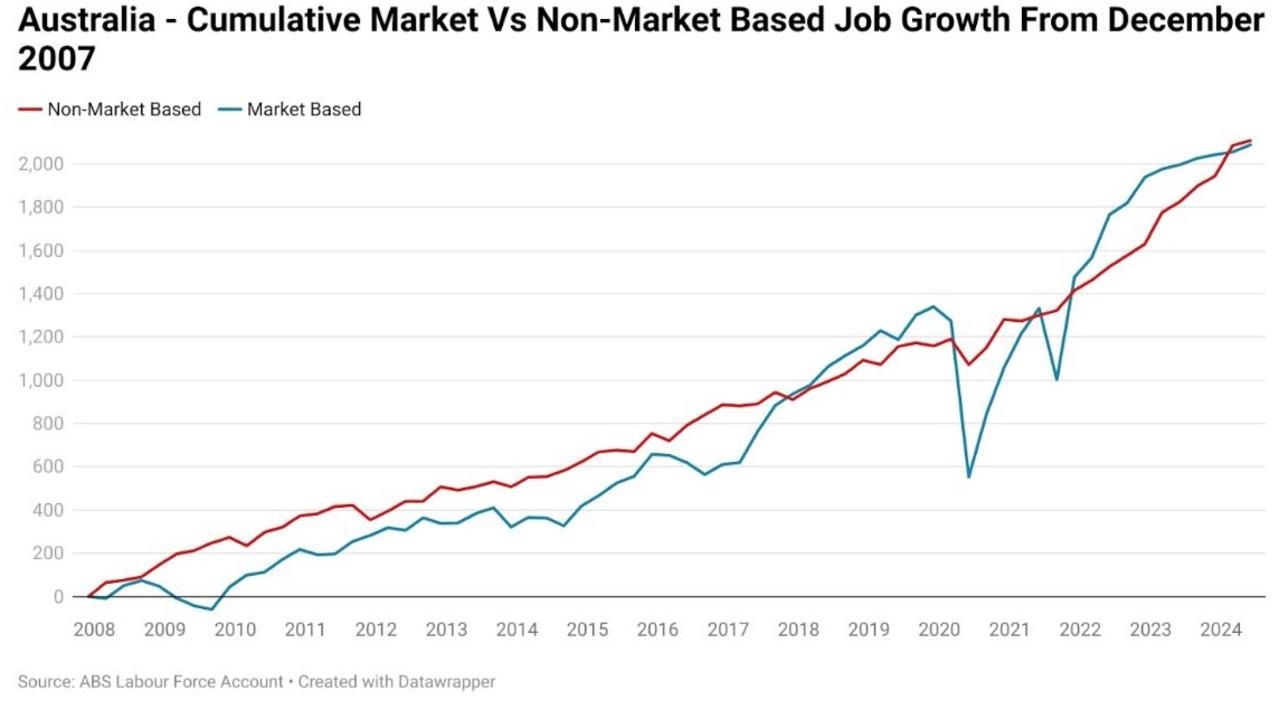

In the 16 years since December 2007 (the start of the US GFC recession), more than half of all cumulative jobs growth has been in non-market industries, despite these industries representing just 21.8 per cent of employment at the start of the data set.

This is not just a reflection of an ageing population either.

Between December 2007 and the latest ABS figures, the proportion of people employed in non-market industries has risen by 34.8 per cent.

By comparison, the proportion of people in non-market jobs in the US rose by 1.75 per cent, by 17.2 per cent in Canada and 16.8 per cent in the UK.

Warning signs

While non-market jobs growth remains at more than triple the average seen in the decade prior to the pandemic, it is beginning to slow from its recent peaks.

The big question is to what degree it will slow – and how swiftly.

In Queensland, the new state government is widely tipped to make job cuts in pursuit of savings for the state budget. Meanwhile, in Victoria, the state budget remains on a troubling trajectory despite the cancellation of the 2026 Commonwealth Games and the sale of state assets such as the partial sell off of VicRoads.

If non-market jobs growth continues to slow and growth in the labour force remains extremely strong, there are risks that unemployment could rise significantly more swiftly and higher than currently anticipated.

Ultimately, the nation’s economy remains uncomfortably reliant on government funded employment growth and there are few if any signs of that reliance drawing to a close.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator