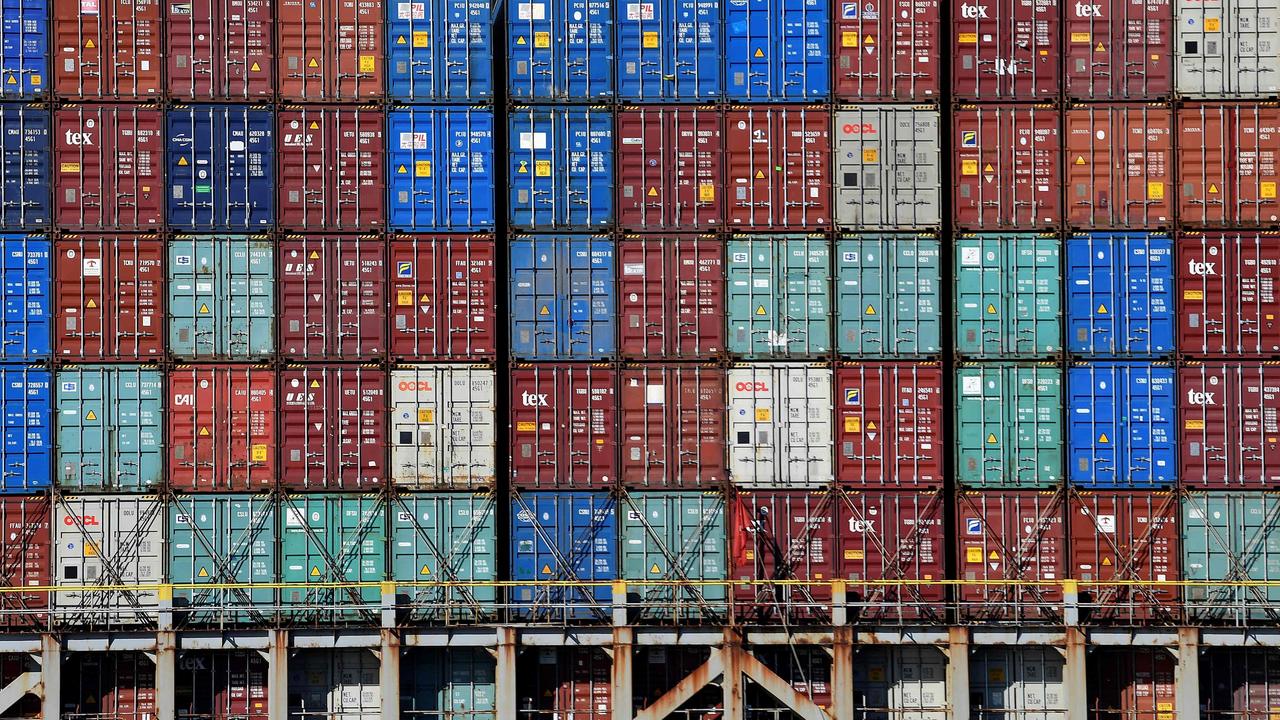

How China’s trade war with Australia backfired

It was meant to be China’s moment to squash Australia but instead it’s been labelled a “spectacular failure”.

Australia hasn’t broken. Eighteen months after Beijing launched its trade war against Canberra, its economic impact was negligible. And the world’s resolve has only hardened.

“I think China’s preference would have been to break Australia. To drive Australia to its knees,” US National Security Council Indo-Pacific affairs advisor Kurt Campbell said earlier this month. “I don’t believe that’s going to be the way it’s going to play out.”

It already hasn’t.

“The bottom line: Beijing’s attempt to bully Canberra has been a spectacular failure,” says USAsia Centre research director Jeffrey Wilson.

And because of Australia’s example, Beijing faces a growing backlash in 2022.

“If this is what decoupling from China looks like, Australia’s resilience suggests the costs are far lower than many have assumed,” added Dr Wilson. “That fact will not be lost on other countries that have differences with China.”

The attempt at economic coercion began in April 2020.

Beijing was incensed that Prime Minister Scott Morrison had made a public call for a wide-ranging investigation into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic in Wuhan. It risked damaging the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) reputation.

So it attempted to silence him. And set an example of what happens to nations that contradict the CCP. Australia’s $150 billion export market with China was its weakest link. So it was hit with a trade war.

Barley. Beef. Coal. Copper. Cotton. Gas. Lobster. Sugar. Timber. Wheat. Wine. Wool.

All were suddenly subject to various tariff, dumping, hygiene and quality challenges. In essence, China stopped buying them.

But Beijing’s seemingly reflexive wolfish aggression triggered an unanticipated response.

Former Australian diplomat Philip Eliason says it triggered a “sacred values” response.

That’s why Australia was so willing to dig in its heels, regardless of the cost.

And that cost has turned out to be unexpectedly small.

When coercion backfires

“Sacred values include the conception of human rights, the role of the individual within society, liberty, justice and the rule of law, and political participation in setting laws,” Mr Eliason argues in the Australian Institute of International Affairs (AIIA) journal Australian Outlook.

“When asked to trade-off sacred values in a deal with a peace dividend, research shows that people typically react with a hostile “backfire effect,” plus an increased commitment to these sacred values and a higher potential for protective violence or preparation for it.”

Australia wasn’t getting a “fair go”.

And Beijing didn’t seem to care much for the idea.

“Beyond differences on values and human rights, Australia is concerned by China’s increasingly belligerent behaviour in the Indo-Pacific,” said Dr Wilson. “China, meanwhile, bristles at what it believes to be Australia’s anti-China stance.”

And that’s fractured a decades-old marriage of convenience.

Making a stand

Canberra no longer hopes China will be gently encouraged towards a more open and tolerant society through trade and interaction on the world stage.

Beijing can no longer rely on Australia being silenced by self-interest, with tens of billions of dollars worth of trade being used as political leverage.

“The trade guns were still smoking when, in November 2020, the Chinese Embassy in Canberra issued a list of “14 grievances” that Australia was expected to correct to return to a normal relationship,” said Dr Wilson.

It included:

– Funding “anti-China” research

– Counter-espionage raids against Chinese journalists

– Academic visa cancellations

– “Spearheading a crusade” against Beijing at international forums

– A Covid-19 origin “witch hunt”

– Banning Chinese tech firm Huawei’s involvement in Australia’s 5G network

– Blocking Chinese investment on national security grounds.

Those grievances have since become something of a badge of pride. Australia handed out copies of the list at the 2021 G7 Summit as an example of Beijing’s behaviour.

“Australia’s response to China will have to both be measured against those of its other international friends and press ahead where it must,” wrote Mr Eliason.

“However, it must also draw on nationally coalescing factors which create an acceptable and comprehensible foundation for national resistance and response to Chinese pressure.”

Australia’s values-based ‘pushback’

“Research on ‘sacred values’ in political negotiations shows that a lack of outcome options, inappropriate negotiating procedures, and poor recognition of emotions set in a context where sacred values are in play, typically causes poor results,” noted Mr Eliason. “China’s diplomatic rhetoric and methods directed at Australia embody these factors.”

Identifying Australia’s “sacred values” isn’t easy.

It’s a multinational country. There’s fundamental disagreement at various levels, such as between the Irish-Catholic and Anglican cultures. And there’s a lot of history between different immigrant groups from the likes of Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Asia.

What binds them together is the search for a better life. The “fair go”.

“For a nationally effective response to the threat of an unfavourable fundamental change in circumstances caused by China, sacred values need to be found, clarified, and called on as required to bolster policy resolve,” wrote Mr Eliason.

And those “sacred values” must be proven to be respected by Canberra in its own behaviour. Or else it may trigger a public opinion “backfire”.

“This may later befall Australian business lobbies because sacred values arguably matter more than money,” Mr Eliason argued.

The era of economic warfare

US National Security Council advisor Mr Campbell said he expected the standoff to be resolved – eventually.

“I fully believe that over time, that China will re-engage with Australia. But it will, I believe, re-engage on Australian terms. I believe that China will engage because it is in its own interest to have a good relationship with Australia.”

Concern about the economic cost of standing up for such principles is declining. As one market closes its doors, others tend to open elsewhere on the international stage.

Australian Treasury estimates put the cost of Beijing’s sanctions at some $5.4 billion. But at least $4.4 billion of that was recovered through finding new markets.

For example, China switched its coal purchase to Russia and Indonesia. That left their previous buyers out in the cold. So, the likes of South Korea and Japan simply turned to Australia.

“(This lead) Australian coal producers’ export earnings to rise this year — not exactly the effect China had in mind,” Dr Wilson concluded. “While the adjustment process is not pain-free, it is far less costly — and less of a deterrent to political action — than most assume.”

And the value of Australia’s exports to China grew – thanks to surging iron ore prices – over the past year. It’s not in Beijing’s interests to interrupt the flow of that strategically vital resource.

“Australia’s experience offers an important lesson: Trade decoupling does not automatically mean trade destruction,” said Dr Wilson. “Indeed, Australia’s resilience may now be inspiring others to take a stand.”

How will Beijing respond to a widespread pushback?

“As countries push back, China’s approach is likely to shift from growing its appeal to pressing its influence,” Mr Eliason warned.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel