China-Australia trade war: Canberra is now Beijing’s whipping boy

There’s a simple explanation for why Australia has become Beijing’s “whipping boy” recently. And the impact could be truly devastating.

First, it was barley. Then beef and coal. Now it’s lobster, timber and wine. Australia faces a stark choice in its economic showdown with China: Bend the knee, or else.

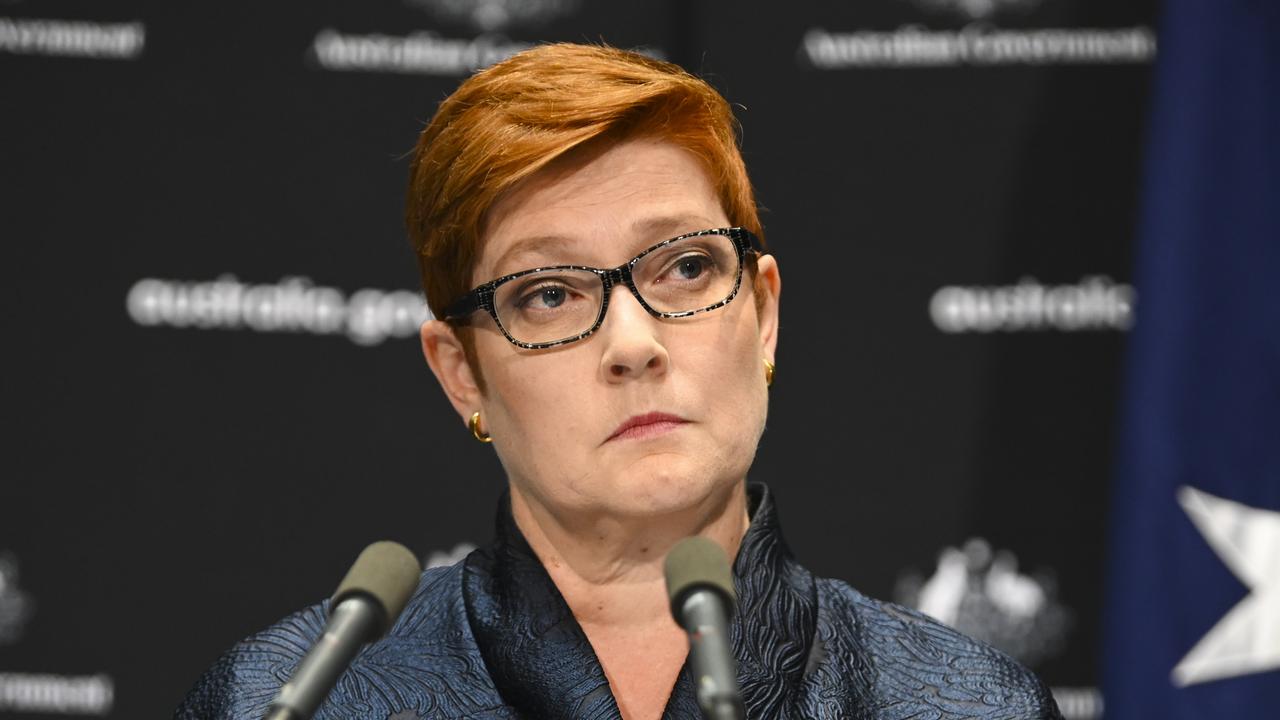

It started in April. Defence Minister Marise Payne took to the world stage to call for a World Health Organisation investigation into the origins of COVID-19.

RELATED: China cracks down on more Aussie goods

Soon after, Australian produce such as barley, copper and sugar products began to be singled out.

It’s a trade war Beijing knows it cannot lose.

“Australia is certainly not engaging in any type of war,” Minister for Trade Senator Simon Birmingham insists.

Research director for the Perth USAsia Centre Dr Jeff Wilson agrees: “A trade war requires two sides to exchange sanctions, this is more like a trade bashing.”

ECONOMIC COERCION

International affairs and trade analysts are scrambling to understand Beijing’s hostility and anticipate its next move.

In effect, analysts argue, Canberra has become Beijing’s whipping boy.

“Australia is perceived by the Communist Party as both an essential target for its close alliance with the US and a soft target for its economic dependence,” one UTS analyst writes. “In short, Beijing can attack Canberra without facing many repercussions – and set an example for the rest of the world.”

RELATED: China’s staggering Australia claim

The impact could be devastating.

“We have conducted simulations of the effect of shutting down Australia-China trade,” economics analysts Professor Rod Tyers and lecturer Yixiao Zhou write in The Conversation. “The effects on Australian gross domestic product and real disposable income per capita are big (6 per cent and 14 per cent), while those on China are mosquito bites by comparison (0.5 per cent and 2.4 per cent).”

Now Beijing won’t even talk with Senator Birmingham or his department.

That’s not likely to change.

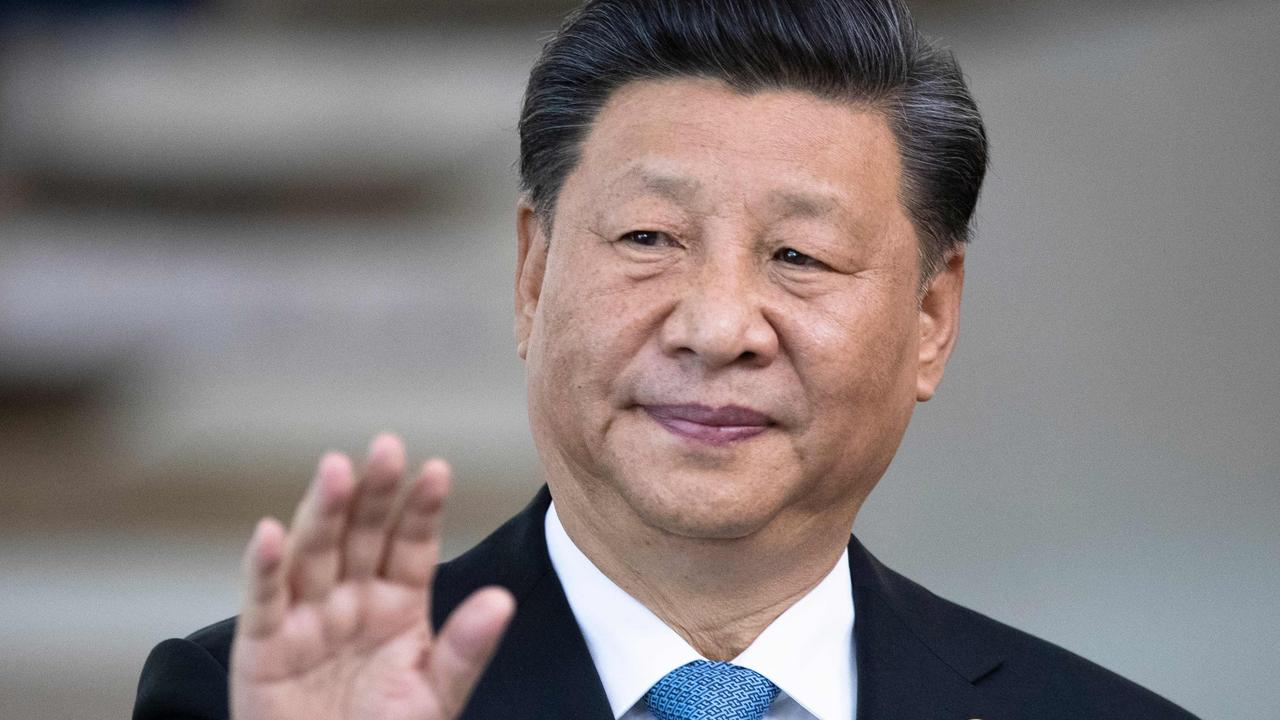

“This is the reality, whether we like it or not,” warns La Trobe University Fellow Tony Walker. “China is done with ‘biding its time’ … It may no longer be correct to describe China as a ‘rising power’. The power has risen.”

‘WRONG THINKING’

“These unrestrained attacks and repeated humiliations of Australia look bizarre, but they are engineered to suit a couple of specific purposes for the totalitarian regime in China: one domestic, the other global,” says associate professor in China Studies, Chongyi Feng.

“Wolf warrior diplomacy,” he says, is aimed at a domestic audience. It’s all about the Communist Party cultivating nationalism through a more aggressive global stance.

This is where Beijing’s policies spill over.

It insists its authoritarian economic and political system is a viable alternative to that established by the West. It knows few believe that. That leaves intimidation.

Which may be why China’s chief diplomat, Zhao Lijian, has accused Australia of “wrong thinking”.

RELATED: Australia’s major China miscalculation

“Responsibility for causing this situation has nothing to do with China,” Zhao insisted in November. “We hope the Australian side will admit to the real reason, look at China and China’s development objectively, earnestly handle our relations based on principles of mutual respect and equal treatment and do more to enhance mutual trust and co-operation.”

TARGET FOR TODAY

Not much of the trade war makes sense. At least not on the surface.

China consumes some 40 per cent of Australia’s exports in a two-way exchange worth roughly $240 billion each year.

But it’s not a balanced equation.

Australia is heavily dependent on this one source of international cash flow. This leaves it economically exposed.

Beijing knows this.

China bought $1.2 billion of Australian wine in 2019-20, equalling some 130 million litres. It has a market of 52 million regular drinkers, making it one of the most lucrative in the world.

And Australian wine isn’t cheap. It’s the second most expensive available on the Chinese market.

“We dismiss these perplexing allegations that somehow Australian wine is dumped onto the Chinese market or sold below market or cost rates,” Senator Birmingham said.

China is yet to impose the tariffs, saying it expects a report in the next 12 to 18 months. Meanwhile, Australian winemakers are frantically seeking alternative markets – potentially leaving Chinese consumers to pay even more.

But it’s a risk Beijing is prepared to take.

“China is angry,” a Chinese official in Canberra said last month. “If you make China the enemy, China will be the enemy.”

STEEL’S ACHILLES HEEL

Australia’s embattled industries are asking: Who is next?

China’s been building cities. It’s been building industry and ports. It’s building the world’s biggest navy.

For this, it needs steel.

And it’s found Australia to be a reliable supplier of its base material – iron.

Exports continue at record highs.

“If China could have found a reliable and plentiful source of iron ore other than Australia, it would have made the switch by now,” ASPI’s Peter Jennings says. “Brazil is unlikely to replace Australia as a stable, cost-effective and long-term supplier. We have a major leverage point if the government is brave enough to step in and start making controls around price and supply.”

But even steel may be an Achilles heel.

And that apparent leverage may not be real.

CHANGE IN THE WIND

“China is changing, transitioning from growth driven by the iron-ore hungry expansion of cities and manufacturing to growth driven more by the supply of services,” Dr Zhou and Professor Tyers argue.

And Professor Blaxland argues Beijing may be turning economic reality to diplomatic advantage.

“China, I think, has been playing a very clever hand at portraying internal domestic market fluctuations for its own political benefit,” he says. “So the drop off in demand for barley, the drop off in demand for wine, or coal, all these things … in China, it’s hard to know exactly the state of the market.

“But when those fluctuations occur, China seems to play them very cleverly, to get the most benefit out of them by making it look like it’s a punishment.”

Beijing still needs steel. And Chairman Xi is urgently pursuing a policy of ‘military-civil fusion’, where industry is being geared to instantly respond to any demand from the People’s Liberation Army. For that, it needs reliable supplies.

Which may be why key Belt and Road projects, such as iron ore and bauxite deposits in Guinea, West Africa and Brazil, continue to be developed. The African deposits “will eventually offer higher quality ore than Australia from a region China may regard as more friendly,” Dr Zhou and Professor Tyers write.

The fallout, they add, will cascade like a tsunami through the extensive support services built around Australia’s mining industry.

“Some commentators place store in our ability to redirect exports of wine and barley, and whatever else is affected by trade disputes, to other customers,” they write.

“At least for iron ore, however, there are few other customers at current volumes. This suggests a decline in export prices and in Australia’s terms of trade.”

CHINESE LESSON

Professor Blaxland says China is trying to teach the world a lesson, with Australia as its example.

“It’s very interesting that it’s happened after the US presidential election, but before President-Elect Biden takes office,” he told a radio interview in India. “It seems to be just in that gap when the United States is distracted (and) debilitated to a certain extent by its response to politics and the pandemic.”

However, he argues Australia has not been ‘singled out’.

South Korea bore the brunt of China’s ire when the US offered to deploy Theatre High Altitude Air Defence (THAAD) air defence weapons systems against North Korean missiles.

“China took this very personally,” Professor Blaxland says. Sanctions were imposed, K-pop music was banned.

“This kind of show is what they call sharp power, the use of China’s market access and influence as a weapon”.

RETURN TO NORMAL?

Beijing’s “ruthlessness in asserting itself far and wide, by fair means and foul, means there will be no going back to the status quo,” La Trobe’s Walker argues.

And, as Lowy Institute analyst Richard McGregor notes: “Beijing routinely directs attacks at its critics through its state-controlled media, regulates local think-tank output, screens foreign investment proposals and regulates the speech of Chinese officials.”

Put simply, it happily restricts trade, prevents foreign investment or ownership, criticises its neighbours and meddles in the affairs of others.

Take, for example, the Belt and Road Initiative agreement with Victoria.

“Needless to say, if a Chinese provincial party secretary signed an agreement with Australia which Beijing had not sanctioned, he or she would be sacked forthwith,” McGregor writes.

But the purpose of Beijing’s diplomatic mixed messaging remains mysterious, ASPI’s Jennings writes. “The CCP’s strategic plan remains opaque, and deliberately so.

“The 14-point grievance list released by the Chinese embassy in late November tells us the issues over which Beijing is unhappy: foreign investment, 5G, anti-interference laws, independent media and noisy think tanks.

“None of this explains how China’s leaders think ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy and military sabre-rattling delivers the global leadership they crave and the deference they demand.”

PRINCIPLES OR PROFITS?

“Some ill-intentioned Australians have pinned the blame on the Chinese side by claiming that China’s control measures on some Australian exports are “economic coercion” and even accusing China of weaponising economic ties,” a Chinese Communist Party-controlled China Daily editorial declares.

“It is both ridiculous and in vain for those in Australia to dress up their country as a victim. Facts speak louder than words.”

The problem for Beijing is, they often do.

But it is counting on them being ignored for being inconvenient.

“It will also not accept the reality of a strong Australia fighting back against Chinese bullying and interference to safeguard its sovereignty, core values and institutional integrity,” says the UTS’ Feng.

“Beijing is flexing its muscles to ensure the submission of Australia and break up an Australia-US alliance based on national interests and shared values. But this is a gross miscalculation that will likely bring about the opposite result.”

TRADE WITH CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS

Canberra can no longer sit on the fence between its long-term ally (Washington) and its economic lifeblood (Beijing), McGregor argues.

“The message is clear. If your media is overly critical, if your think-tanks produce negative reports, if your MPs persist in criticism, if you probe Communist party influence in your community and politics and if you don’t allow Chinese state and private companies into your market, and so on, you will be vulnerable to Beijing’s retribution as well.”

Beijing is demanding respect. And compliance.

But Walker argues Canberra must avoid acts that “needlessly antagonise” our biggest customer.

“Again, this is not making a case for excusing China’s bad behaviour, or somehow suggesting the customer is always right. It is simply saying that gratuitous provocations should be avoided,” he says.

Australia’s economic interests, Walker warns, are being wedged out of the debate.

“The business community, for example, has been discouraged – even intimidated – from voicing its opinion out of concern it would be accused of pandering to Beijing for its own selfish reasons,” he says.

Canberra is, pursuing a “one-dimensional stand up to Chinese bullying” approach:

“This is hardly a substitute for a carefully thought-through, well-articulated, tough-minded approach to managing a highly complex relationship in the national interest.”

CAN SOFT POWER PREVAIL?

“Beijing’s crude use of trade sanctions to penalise Australia for real or imagined slights signifies that (any) trading relationship born of mutual benefit risks being subject to persistent, politically-motivated interference,” Walker warns.

Beijing seems unconcerned by these obvious implications.

Australia is being made an example of. The intention is to make nation-states think twice about similarly crossing Chairman Xi.

But those same states may also hesitate about further exposing themselves through trade to such an antagonistic partner.

And that, in turn, could unsettle Mr Xi’s own populace.

“There is rising resentment among some Chinese to Xi’s rule, and the country faces enormous political, economic and social challenges,” Dr Feng argues. “As such, Xi lives with a profound sense of insecurity. And his arbitrary rule and desire for absolute control make everyone else feel insecure.”

Not only must the Chinese people remain controlled by the Communist Party. They must be kept content.

“Demand for exports like food, wine, timber, education and tourism comes from Chinese consumers,” Jennings adds. “The CCP might see a tactical political advantage from imposing bans or tariffs, but it does so at the risk of annoying its own people, from whom the party seeks legitimacy.”

The result is a tangled web of conflicting interests.

“Can we possibly make up with China?” Professor Blaxland asks. “My sense is that we can’t do so without having to bend the knee and act in a way that will be humiliating for the government. And that is politically not marketable, not palatable, for the government to do.”

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @JamieSeidel