Disaster looming in Australian economy as iron ore demand falls

Australia’s “luck” relies on China and it seems as though that luck is about to run out. The ramifications could be far reaching.

When the global financial crisis kicked off in 2008, there were concerns that Australia could follow most of the rest of the developed world into recession. But like so many times before and since, Australia’s luck came to its rescue.

As if lady luck dropped good fortune on Australia herself, the nation became one of precious few around the world to avoid a major recession and potential housing market crash.

Unprecedented Chinese stimulus saw more cement poured in two years than the United States did in the entire 20th century, commodity prices rocketed, coming to the aid of the economy and the Treasury’s coffers at just the right time.

Between December 2007 and February 2011, the price of iron ore rose more than 400 per cent.

Meanwhile, between February 2009 and February 2011, the price of coking coal, a key input into manufacturing steel more than doubled in price.

The Lucky Country’s luck had well and truly come to Australia’s aid at the perfect time, but the bounty provided by China’s insatiable demand for bulk minerals was only just beginning.

Between mid-2009 and its peak in early 2012, mining investment more than doubled as new mines were built, infrastructure constructed and services put in place. At the time this lead to a huge ramp up in wages in the mining sector and filtered through to the rest of the economy in the form of higher consumer spending.

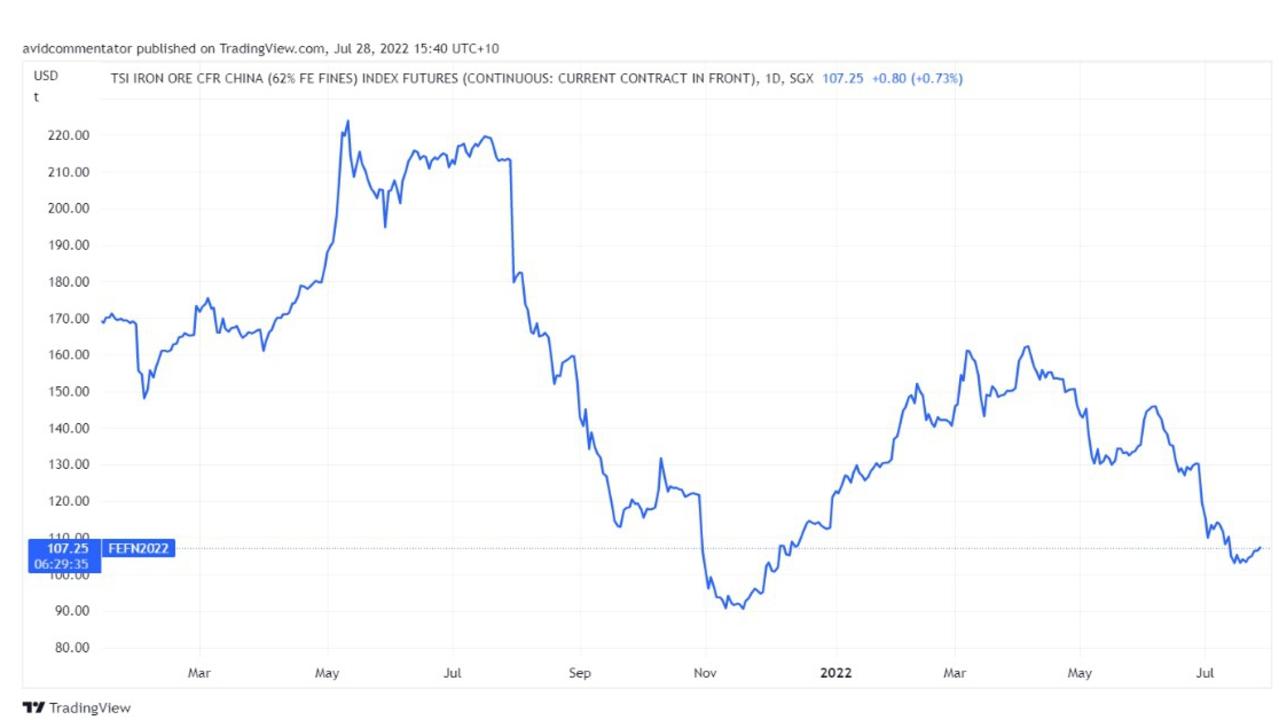

Amid the recent pandemic, history didn’t quite repeat itself but it certainly rhymed, as iron ore prices rocketed 151 per cent between the end of 2019 and their peak in May 2021.

While the support provided by Chinese commodity demand did not provide the same duration and magnitude as it did in 2008, it was still a major boon to the economy and the Treasury’s coffers.

But now as the Chinese economy continues to deteriorate due to a slowing global economy, Beijing’s Covid-zero strategy and the woes of China’s property sector, Australia’s boon risks combining with other factors for the nation’s decade’s long run of good fortune to come to an end.

China’s property sector dilemma

In the years following the global financial crisis, the approach of the Chinese government toward large property developers in trouble was generally to throw money at the problem until it went away. That is up until about 18 months ago, from which time the Chinese government became far more discerning regarding its intervention in the property sector.

With the Chinese government now far less frequently choosing to come to the rescue and dedicating only a tiny fraction of the resources required to fix the sector’s short-term financial issues outright, the property sector has continued to deteriorate.

While some degree of deterioration is to be expected due to the pandemic and China’s ongoing Covid-zero strategy, the amount of residential floor space under construction has plunged more than 39 per cent compared with May last year.

The number of new residential projects under construction has also fallen more than 41 per cent compared with May last year.

According to an analysis by Bloomberg, construction halts could impact 4.7 trillion yuan ($995 billion AUD) worth of homes across China, with 1.3 trillion yuan ($A275 billion) required to complete them.

Understandably the prospective homeowners who are currently paying a mortgage on a property that has paused construction are extremely frustrated with the situation. It’s normally at this point that the Chinese government rides to the rescue, bails out the developers and things proceed as per usual.

But that isn’t happening, so the citizens impacted by these construction halts have taken an equally unprecedented move for China, simply refused to pay their mortgages. According to estimates from analysts at Bloomberg tens of thousands of impacted home buyers have refused to pay their loans.

Crowd sourced data concluded that the mortgage boycott is impacting more than 320 development projects across all of China.

On Monday, it was announced that the People’s Bank of China (Chinese central bank) and the China Construction Bank would be launching a 300 billion yuan ($64 billion) fund to help support developers and complete projects through potential commercial bank loans.

On paper this sounds like quite a major commitment, but when put into the context of an industry that generates more than $7.6 trillion worth of China’s GDP, it’s a drop in a very large ocean.

Going forward

This brings us back to the Lucky Country. In recent weeks it has slowly been dawning on commodity markets that the expected huge Chinese construction driven stimulus program may not be coming.

Since their recent peak in early April, iron ore prices have fallen more than 34 per cent. This comes amid global steel production falling by 5.5 per cent in the first half of 2022, driven in large part by falling output in China.

The big question now is does Beijing deliver a big spending construction driven stimulus program? Or a far larger and broad based series of support measures for the property sector? If the answer to both those questions is no and Beijing instead chooses to focus its resources on supporting households and businesses impacted by the pandemic, then demand for bulk commodities may remain weak.

For well over a decade the Lucky Country has feasted on the bounty that Chinese demand for Australian minerals has provided, it has underpinned everything from state and federal budgets, all the way through the strength of our currency.

Once again Australia is staring down yet another global economic downturn and we get to see if the Lucky Country’s run of good fortune can be extended yet further.

Tarric Brooker is a freelance journalist and social commentator | @AvidCommentator