Canadians face hefty penalties for leaving homes empty — should Australia follow suit?

As Australia’s housing crisis continues to worsen, attention is again turning to the country’s one in ten “empty” homes.

As Australia’s housing crisis continues to worsen, attention is again turning to the country’s one in ten “empty” homes — and whether more needs to be done to fill them up.

While some parts of Australia are attempting to boost housing supply by cracking down on vacant homes and land, a viral post on Reddit this week questioned whether a more aggressive Canadian-style empty homes tax was the way forward.

“We are in this bizarre situation in Australia where two decades of inaction have left us so far behind the eight-ball that we’re playing catch-up and madly looking around at crazy ideas,” said University of Adelaide Professor of Housing Research Emma Baker.

“It’s now so bad that we’re starting to talk about holiday homes.”

One million ‘empty homes’

There were more than one million “empty” homes in Australia on Census night in 2021, a headline-grabbing figure in the midst of the country’s worsening housing crisis.

ANU demographer Dr Liz Allen told ABC Radio Melbourne in 2022 that the number “punched me in the face”.

“That’s extraordinary when we are grappling with the most difficult housing affordability times we’ve seen and dealing with homelessness on the scale that we are,” she told host Waleed Aly.

“There are a number of reasons for that vacancy rate, but a lot of that is because people have multiple homes.”

But the unoccupied dwelling figure of 9.6 per cent cited by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) has remained relatively steady at roughly one in 10 for decades — it was 11.2 per cent in the 2016 Census, 10.7 per cent in 2011 and 10.3 per cent in 1986.

In a piece for The Conversation, Prof Baker and her colleagues pushed back on what they saw as some of the “puff” around the one million number.

“Everyone had come away with the ABS headline saying ‘one million empty homes’ and were wringing their hands about how they could make the empty homes full again,” she said.

“But when you look underneath the bonnet of ‘one million empty homes’, you see that headline is largely an artefact of the way [the ABS] counts homes.”

The bulk of that number, according to Prof Baker, is likely miscounted due to the Census form simply not being returned — for example if the resident does not speak English.

“Then when we map where those apparently empty homes are, they’re largely in the sea-change and sometimes treechange parts of Australia, which suggests to us there’s a lot of holiday homes,” she said.

“Lots of Australian families have a holiday home that they use sometimes, and they probably won’t be using it on August 8 in the middle of winter.”

Around two million Australians own a second home, with an estimated 347,000 of those listed on Airbnb alone, according to Prof Baker.

Thirdly, at any given time a certain percentage of homes will be unoccupied as they are up for sale or awaiting transfer.

The bottom line is that we need to “think a bit more deeply” about “what we would call ‘empty homes’”. “There are lessons for us in solving the housing crisis, but they’re probably not under the one banner of filling up the empty homes,” Prof Baker said.

Australia’s vacancy taxes

Australia currently has a patchwork of different vacancy fees and taxes at a national, state and local level.

Nationally, foreign owners of residential dwellings are charged a vacancy fee if the home is not residentially occupied, “genuinely available” on the rental market, and rented out for at least six months a year.

Foreign owners are required to lodge a vacancy fee return form with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) each year. If their dwelling is vacant, they must pay the vacancy fee, which is typically the same as the fee they paid when they submitted their original residential property or exemption certificate application.

In December, Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced those fees would be massively increased in a new crackdown on foreign investors who buy homes and leave them empty.

The proposed changes, to be brought to parliament this year, will both triple the initial application fees for foreign investors while doubling the vacancy fee, meaning the vacancy fee will increase sixfold from its current level.

Under the existing scheme, a foreigner who buys a $1.1 million home pays $28,000 in application fees and $28,000 again each year it is left empty. The changes will mean the same property will attract an $84,000 application fee and an annual vacancy tax of $169,000.

“These adjustments are all about making sure foreign investment aligns with the government’s agenda to lift the nation’s supply of affordable housing,” Mr Chalmers told The Sunday Telegraph.

“The increased vacancy fees will encourage foreign investors to make their unused properties available to renters.”

At the state level, Victoria has the most aggressive policy with its vacant residential land tax, which applies to homes that have been unoccupied for more than six months and is charged at 1 per cent of the total value of the property.

Last year, Victorian Treasurer Tim Pallas announced the tax would be expanded to also apply to undeveloped land and empty properties across the state, including regional areas, starting January 2025.

Previously the tax only applied to 16 council areas covering Melbourne’s inner and middle-ring suburbs. Victoria’s tax allows for some exemptions, however, including for holiday homes.

“We can’t afford really to have vacant land in metropolitan Melbourne sitting idle for year on year,” Mr Pallas said. “Our clear message to landowners is to either develop the land or sell it to someone who will.”

But NSW Premier Chris Minns last year ruled out following Victoria’s lead, saying the government would instead focus on planning and zoning reforms to tackle supply and affordability issues.

“No, I’m not announcing that [an empty home tax],” he said at a media conference in western Sydney alongside Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. “You can do many things when it comes to housing supply and ensuring that there’s enough dwellings … but we’re going to focus on bringing on more supply.”

And at the local level, Brisbane and Hobart have both introduced forms of an “Airbnb tax” in recent years to crack down on short-stay accommodation.

Brisbane City Council charges a 65 per cent rate surcharge on properties listed for short-term rental for more than 60 days a year, while Hobart City Council charges double and also imposes higher rates for owners of vacant residential land.

Canada’s ‘landmark’ solution

In Canada, the province of British Columbia introduced a vacancy tax in 2018 in the face of an “out of control” housing crisis, which the government in part blamed on speculators driving up prices, taking rental properties off the market and leaving homes empty.

BC’s Ministry of Finance recently published an analysis that found the “landmark solution” was working to address the crisis, helping to add approximately 20,000 units to the long-term rental market in Vancouver.

Over three years, the province also collected around $C230 million ($260 million) in revenue from the vacancy tax and recorded a decline in foreign buyers.

But University of British Columbia professor Tsur Somerville, who co-authored the analysis, told the ABC last year that the vacancy tax wasn’t a silver bullet.

“It [had] an effect, but when you’re dealing with affordability crises, [a vacancy tax is] not moving the needle and solving the problem in and of itself,” he said.

“I don’t think there was any expectation that this [tax] was magically going to solve all those problems, but at least contribute to reducing the incentive for people to hold property. Things [still] got worse, but they didn’t get worse as much.”

The vacancy tax is charged at 0.5 per cent of the property’s value for Canadian citizens and residents and 2 per cent for foreign owners.

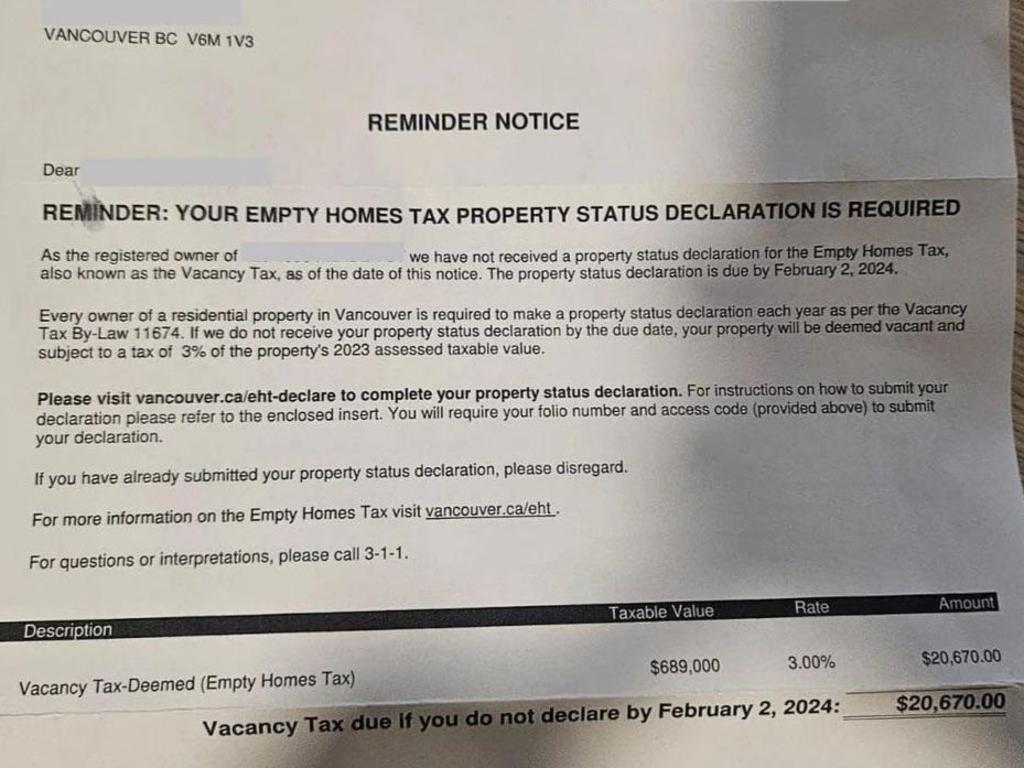

Separate to the provincial tax, the city of Vancouver introduced its own empty homes tax in 2017 at 1 per cent of the property’s value, which has since increased to 3 per cent.

All property owners in covered areas are required to fill out vacancy declarations each year, and face heavy penalties for not doing so.

People who own a home in Vancouver must complete both the municipal and provincial declaration each year, and may have to pay both taxes.

The viral photo posted to Reddit recently showed one Vancouver homeowner’s reminder notice to complete their empty homes tax declaration by February 2 — or face a bill of $C20,670 ($23,350).

As the ABC noted, the key difference between the approaches in Australia and Canada is this level of accountability.

“Everyone is essentially liable for this tax unless you live in the property yourself, or a family member was living in it, or it was rented out for at least six months of the year,” Prof Somerville said.

‘Fiddling while housing burns’

Overall, experts tend to agree that vacancy taxes are not a bad idea to boost housing availability — but too much focus on “empty” homes distracts from much bigger drivers of the crisis.

Even cracking down on foreign investors leaving homes empty “definitely isn’t enough to solve the housing crisis”, according to Prof Baker.

“These vacancy charges and taxes are actually pretty good policy as long as they’re not incredibly tough,” she said.

“If you’re thinking about that million, the bit that you probably want to hit and bring over to the housing supply stock is the bit that are genuinely just being held empty for asset appreciation. Vacancy taxes are quite good at targeting that, it’s not forcing people not to hold property for asset appreciation but it gives it a good nudge.”

But she warned that it was “focusing our gaze in slightly the wrong direction anyway”.

“If what we want to be doing is housing people, especially housing people in the parts of Australia where there’s access to jobs, we need to be thinking about who in our population needs homes, what kind of housing we should actually be building, and where,” she said.

“That’s not going to be three hours from Adelaide on a beautiful beach somewhere.”

MacroBusiness chief economist Leith van Onselen agreed that “the last thing you want during a housing crisis is for homes to lay vacant”.

“So, at the margin, if you’re going to tax vacant homes it should bring some of them to market and should boost effective housing supply,” he said. “But the impact of a vacant homes tax is likely to be very small. It is really fiddling while the housing system burns.”

He argued the “main problem is nations like Australia and Canada run extraordinarily large immigration programs that are well beyond their ability to supply homes and infrastructure”.

“These extreme immigration programs have created chronic housing shortages in both nations,” he said.

“So, the real solution to the housing crisis is to significantly lower immigration so housing and infrastructure can keep pace with population growth.”

But Prof Baker said the focus, rather than on immigration, should be on building more homes at greater density, and with more efficient use of building materials.

“In a time of material and labour shortages we should really be trying to get the maximum number of dwelling outcomes per kilogram of building material and hour of worker,” she said.

“That probably suggests building big five-bedroom homes is not the best idea.”